The 2026 Landscape, Emerging Trends, and Comprehensive Defense Strategies

Executive Summary

The intersection of civil rights law and digital infrastructure has reached a critical inflection point as we approach 2026. For nearly three decades, the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) has served as the bedrock of physical accessibility in the United States. However, the translation of these mandates into the digital realm—specifically regarding websites, mobile applications, and digital kiosks—has historically been characterized by regulatory ambiguity and judicial inconsistency. This era of uncertainty has definitively ended. The transition from 2024 to 2025 has witnessed a convergence of regulatory solidification, aggressive enforcement against deceptive technological “fixes,” and a profound shift in the mechanics of litigation itself.

Businesses operating in the United States now face a trifecta of pressures: the Department of Justice’s (DOJ) finalization of Title II regulations, which sets a de facto national standard; the Federal Trade Commission’s (FTC) decisive crackdown on accessibility overlays; and the industrialization of litigation through Artificial Intelligence (AI). In 2024 alone, plaintiffs filed 4,187 lawsuits alleging digital inaccessibility.1 While federal filings have shown some stabilization, the migration of lawsuits to state courts—particularly in New York and California—has created a more complex and costly defense environment. Furthermore, the rise of pro se litigants, empowered by generative AI to draft complaints and identify technical violations without legal counsel, threatens to overwhelm court dockets and corporate legal departments alike.2

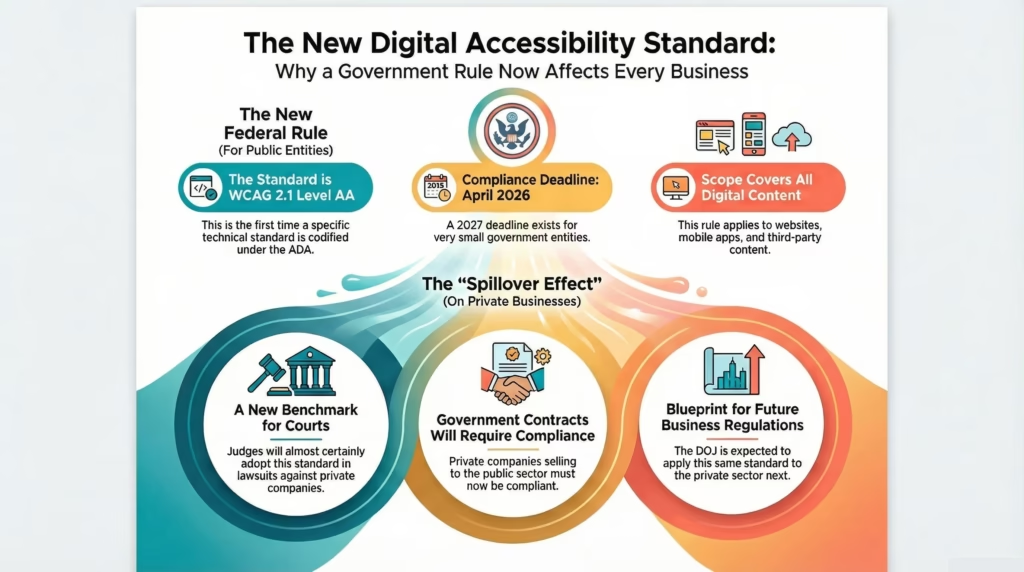

As we look toward 2026, the compliance deadline for public entities under Title II (April 2026) will create a massive spillover effect, cementing the Web Content Accessibility Guidelines (WCAG) 2.1 Level AA as the non-negotiable standard for the private sector.3 This report offers an exhaustive analysis of these developments, dissecting the statistical trends, the evolving legal theories regarding “standing,” and the operational imperatives for businesses seeking to mitigate risk in an increasingly litigious digital economy.

1. The Historical Context and Evolution of ADA Title III

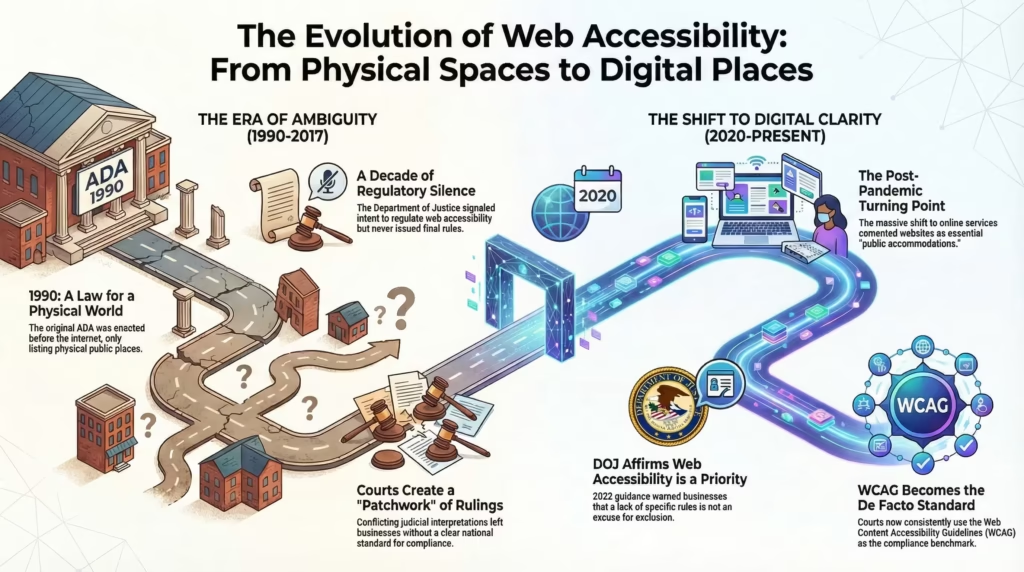

To understand the ferocity of the current litigation landscape, one must first analyze the historical vacuum that allowed it to proliferate. Title III of the ADA prohibits discrimination on the basis of disability in “places of public accommodation.” Enacted in 1990, long before the ubiquity of the commercial internet, the statute listed twelve categories of physical spaces—such as hotels, restaurants, and libraries—as covered entities. It did not, and could not, explicitly list “websites.”

1.1 The Era of Regulatory Ambiguity (2010–2023)

For over a decade, the Department of Justice, charged with enforcing the ADA, maintained that the ADA applied to websites but failed to issue specific technical standards for compliance. In 2010, the DOJ issued an Advanced Notice of Proposed Rulemaking (ANPRM) signaling its intent to regulate web accessibility, only to withdraw it in 2017 under an administration focused on deregulation.3 This withdrawal left a regulatory void. In the absence of clear federal regulations, the courts stepped in to fill the gap.

This judicial intervention resulted in a patchwork of conflicting interpretations. Some courts, adhering to a strict textualist interpretation, ruled that the ADA applied only to physical spaces. Others developed the “nexus theory,” arguing that a website is covered only if it facilitates the use of a physical location (e.g., a website allowing a user to order a pizza for pickup). A third group of courts adopted the “standalone” theory, recognizing that in the modern economy, a website is the place of business, rendering the physical nexus irrelevant. This fragmented legal landscape emboldened the plaintiff bar, allowing firms to “forum shop” for jurisdictions with the most favorable interpretations of the law.

1.2 The Shift to Digital Civil Rights

The narrative shifted dramatically in the post-pandemic world. As commerce, education, and essential services moved almost exclusively online, the argument that websites were merely “conveniences” rather than essential public accommodations collapsed. By 2024, the legal consensus had largely solidified around the applicability of the ADA to digital assets, even if the specific technical standards remained uncodified for the private sector. The Department of Justice’s guidance in March 2022 reiterated that web accessibility is a priority, effectively warning the private sector that the absence of a specific regulation was not a license for exclusion.4

This historical context is crucial for understanding 2026 trends because the patience of both the judiciary and the regulatory bodies has worn thin. The “lack of notice” defense—the argument that businesses didn’t know how to comply—has been systematically dismantled by successive court rulings and settlements citing the Web Content Accessibility Guidelines (WCAG) as the industry standard.5

2. The 2024-2025 Litigation Landscape: A Statistical Deep Dive

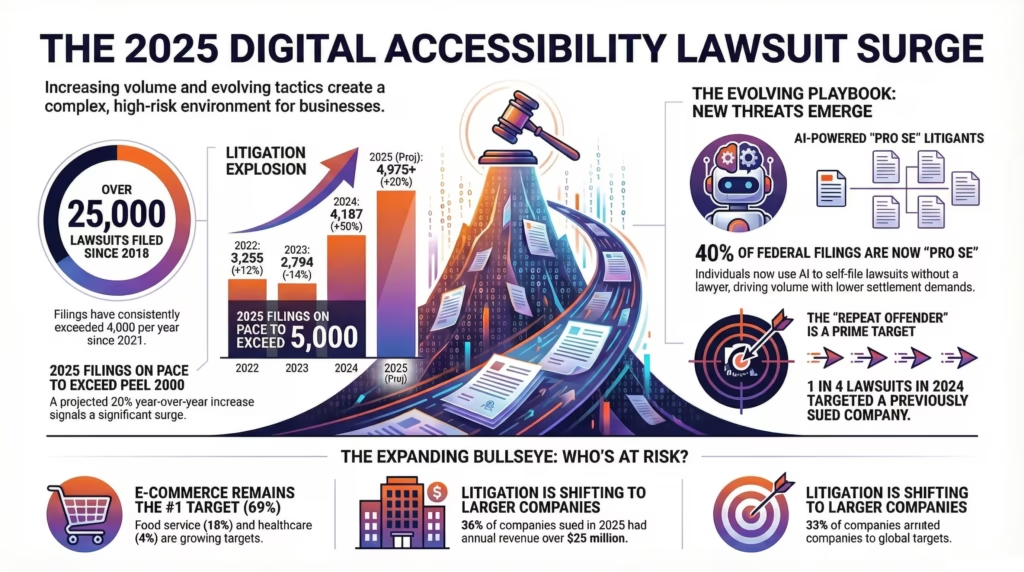

The data from 2024 and the first half of 2025 reveals a litigation environment that is not only growing in volume but evolving in sophistication and strategy. The “spray and pray” tactics of early serial filers have been refined, and new players have entered the arena, leveraging technology to increase the velocity of filings.

2.1 Volume and Velocity of Filings

By the end of 2024, plaintiffs had filed 4,187 lawsuits alleging digital inaccessibility in federal and state courts.1 This figure represents a stabilization at a historically high plateau; since 2021, the number of lawsuits has consistently exceeded 4,000 annually. Between 2018 and 2025, over 25,000 such lawsuits were filed.1

However, these top-line numbers obscure a more troubling trend in 2025. Data from the first half of 2025 indicates a potential surge. EcomBack reported a 37% year-over-year increase in federal filings in the first six months of 2025 alone.6 If this trajectory maintains its course, total filings for 2025 could approach or exceed 5,000, and projections for 2026 suggest a breach of the 5,500 mark.7

Table 1: Annual ADA Digital Accessibility Lawsuit Filings (2018–2025)

| Year | Total Lawsuits | Growth Trend | Key Driver |

| 2018 | 2,258 | +177% | First major wave following Gil v. Winn-Dixie. |

| 2019 | 2,256 | Flat | Stabilization of initial surge. |

| 2020 | 2,523 | +14% | Pandemic-driven shift to digital commerce. |

| 2021 | 2,895 | +12% | Expansion into new industries (healthcare, education). |

| 2022 | 3,255 | +12% | Increased state court filings. |

| 2023 | 2,794 | -14% | Temporary dip due to pending Supreme Court decisions. |

| 2024 | 4,187 | +50% | Surge in state filings (NY/CA) and “Pro Se” litigants. |

| 2025 (Proj) | 4,975+ | +20% | AI-generated complaints and overlay targeting. |

Sources: 1

2.2 The Rise of the “Pro Se” Litigant

One of the most disruptive trends to emerge in 2024-2025 is the explosion of pro se litigation—lawsuits filed by individuals representing themselves without an attorney. Seyfarth Shaw reports that pro se plaintiffs now account for approximately 40% of federal ADA Title III filings.2

This phenomenon is inextricably linked to the democratization of Artificial Intelligence. In previous years, filing a federal lawsuit required a certain level of legal acumen or the retention of a specialized firm. Today, generative AI tools can draft a coherent complaint in seconds, citing relevant statutes and detailing alleged barriers. Simultaneously, automated accessibility scanning tools allow these individuals to identify technical violations (such as missing alt text or empty links) without possessing any technical expertise.

The implications of this shift are profound:

- Lower Settlement Thresholds: Pro se litigants often demand smaller settlements than law firms, viewing the litigation as a volume business. However, their lack of professional obligation can make them volatile negotiators.

- Increased Frivolity: AI tools often “hallucinate” or misinterpret legal standards. Courts are seeing an increase in complaints citing non-existent case law or alleging violations that are technically impossible.9

- Resource Drain: Even a frivolous pro se lawsuit requires a defense. Businesses are forced to spend thousands of dollars on counsel to dismiss complaints that, in a previous era, would never have been filed.

2.3 The “Repeat Offender” Crisis

A critical failure in corporate defense strategy is the treatment of ADA lawsuits as a one-time “cost of doing business.” The data explicitly refutes this approach. In 2024, one in four lawsuits involved a company that had been sued previously for the same or similar issues.10 Companies received 961 repeat lawsuits, representing over 40% of all cases.10

This statistic highlights a dangerous cycle: a company settles a lawsuit but fails to fundamentally remediate its website. Or, it remediates the site but fails to maintain it, allowing new content to introduce new errors. In the eyes of the plaintiff bar, a company that has settled once is a prime target for a second lawsuit because the settlement typically does not include a permanent injunction against other plaintiffs.

2.4 Industry Analysis: The Expansion of Targets

While e-commerce remains the primary target, accounting for 69% of filings in 2025 11, the scope of litigation has broadened significantly.

- Food Service (18%): Online ordering systems and digital menus are frequent targets.11

- Healthcare (4%): As patient portals become essential for care, they are increasingly scrutinized.11

- Education: With the Title II regulations looming, private universities and trade schools are being targeted under the “nexus” of federal funding and public accommodation.

Interestingly, the size of the target is shifting upward. In the first half of 2025, 36% of sued companies had annual revenue exceeding $25 million, up from 33% in 2024.1 This suggests that plaintiff firms are becoming more strategic, targeting entities with deeper pockets and greater reputational risk aversion, likely to secure higher settlements.

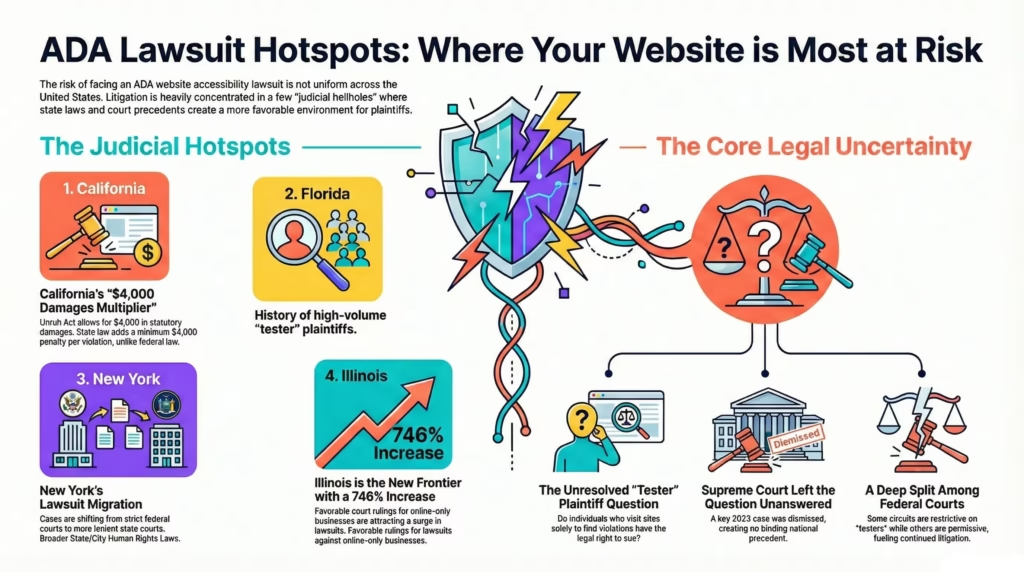

3. The Judicial Geography and The “Standing” War

The United States is not a monolith when it comes to ADA litigation. The risk profile of a business depends heavily on where it is sued. The battleground has shifted from the merits of the case (e.g., “Is the website accessible?”) to technical arguments regarding jurisdiction and standing (e.g., “Does this plaintiff have the right to sue?”).

3.1 The Jurisdiction Split: “Judicial Hellholes”

The vast majority of litigation is concentrated in three states: New York, California, and Florida. However, 2025 saw the emergence of Illinois as a new hotspot.

Table 2: Top States for ADA Title III Filings (Mid-Year 2025)

| Rank | State | Filings | Key Legal Driver |

| 1 | California | 1,735 | Unruh Civil Rights Act allows for $4,000 statutory damages per violation. |

| 2 | Florida | 989 | Historically high volume of “tester” plaintiffs; 11th Circuit precedent. |

| 3 | New York | 837 | NY State/City Human Rights Laws provide broader coverage than federal ADA. |

| 4 | Illinois | 270 | 746% increase; favorable rulings in the 7th Circuit regarding online-only businesses. |

| 5 | Texas | 116 | Growing volume in the 5th Circuit. |

Sources: 6

The New York Migration:

New York federal courts (Second Circuit) have historically been the busiest venues. However, recent decisions by judges in the Southern District of New York (SDNY) have begun to scrutinize “tester” standing more rigorously, dismissing cases where the plaintiff cannot prove a concrete intent to return to the website.8 This judicial pushback has caused a migration of cases from federal court to New York State court. The New York State Human Rights Law (NYSHRL) and New York City Human Rights Law (NYCHRL) are interpreted more broadly than the federal ADA, often allowing plaintiffs to plead “dignitary harm” without the strict “injury-in-fact” required by Article III of the US Constitution.14

The California Damages Multiplier:

California remains the leader in filings primarily due to the Unruh Civil Rights Act. Unlike the ADA, which allows only for injunctive relief (fixing the site) and attorney’s fees, the Unruh Act incorporates the ADA and adds a statutory penalty of $4,000 per occurrence.15 This financial incentive makes California the most dangerous jurisdiction for defendants, as a single lawsuit carries a guaranteed price tag significantly higher than in other states.

The Rise of Illinois:

The sharp 746% increase in Illinois filings is a direct result of forum shopping.6 With New York federal judges becoming hostile to serial testers, plaintiff firms are moving to the Seventh Circuit (which covers Illinois, Indiana, Wisconsin). The Seventh Circuit has arguably been more receptive to the “standalone website” theory (that a website is a public accommodation regardless of physical nexus) than other jurisdictions, making it fertile ground for lawsuits against online-only businesses.5

3.2 The Supreme Court and the “Tester” Question

The most significant legal question of the era remains unresolved: Do “testers”—individuals who visit websites solely to find violations for litigation—have constitutional standing to sue?

The Supreme Court was poised to answer this in Acheson Hotels, LLC v. Laufer. The plaintiff, Deborah Laufer, had filed hundreds of lawsuits against hotels for failing to provide accessibility information on their reservation websites. However, in December 2023, the Supreme Court dismissed the case as moot because Laufer voluntarily dismissed her claim before the Court could rule.17

While the Court did not issue a binding precedent, the concurring opinion by Justice Clarence Thomas signaled a deep skepticism toward tester standing. He argued that a plaintiff who has no intention of visiting a hotel suffers no injury when the website lacks accessibility information.18 This “non-decision” has left the Circuit Courts split:

- Restrictive Circuits (2nd, 5th, 10th): Increasingly demand concrete proof of intent to use the service.

- Permissive Circuits (11th, 9th): Have historically allowed tester standing based on the “stigma” of discrimination.

This continued ambiguity ensures that litigation will continue unabated, as plaintiff firms simply tailor their complaints to the specific pleading standards of the jurisdiction they are filing in.

4. The Regulatory Tipping Point – DOJ Title II Rule

If the litigation landscape represents the “stick” of private enforcement, the Department of Justice’s recent rulemaking represents the “stick” of federal regulation. On April 24, 2024, the DOJ published its final rule updating Title II of the ADA, focusing on the accessibility of web content and mobile apps for state and local governments.3

4.1 The Specifics of the New Rule

The Title II rule is the first time the federal government has codified a specific technical standard for web accessibility under the ADA.

- The Standard: The DOJ adopted WCAG 2.1 Level AA as the technical standard.3

- The Timeline: Public entities must comply by April 24, 2026 (or April 2027 for very small entities).3

- Scope: The rule covers all web content, mobile apps, and social media provided by the public entity or by third parties on their behalf.

- Exceptions: The rule creates narrow exceptions for archived content, pre-existing conventional electronic documents (like old PDFs), and individualized password-protected documents.3

4.2 The Rejection of WCAG 2.2

Notably, the DOJ chose WCAG 2.1 over the newer WCAG 2.2, which was released in late 2023. The Department reasoned that WCAG 2.1 was the mature, settled standard during the rulemaking process. This decision provides a crucial “safe harbor” benchmark for businesses. While WCAG 2.2 is the best practice, WCAG 2.1 AA is the legal standard.3

4.3 The “Spillover Effect” on the Private Sector (Title III)

Although Title II applies only to public entities, its impact on the private sector (Title III) will be absolute and transformative. Legal experts anticipate a “spillover effect” driven by three mechanisms:

- Judicial Benchmarking: Courts presiding over Title III cases against private businesses have long struggled to define “accessibility” without a federal regulation. With the DOJ explicitly endorsing WCAG 2.1 AA for the public sector, judges will almost certainly adopt this as the standard for “effective communication” in the private sector. It removes the defense that the ADA is “too vague”.3

- Procurement Mandates: Private companies that do business with state or local governments (B2G) must ensure their products are WCAG 2.1 AA compliant by 2026. A SaaS provider selling scheduling software to a school district, for example, must be compliant. This forces the entire technology supply chain to upgrade its standards.

- Future Title III Rulemaking: The Title II rule is widely viewed as a blueprint for a future Title III regulation. The DOJ has signaled that the private sector is next, and it is highly unlikely they would adopt a different standard for private businesses than for public ones.3

5. The Technology Trap – Overlays, AI, and the FTC

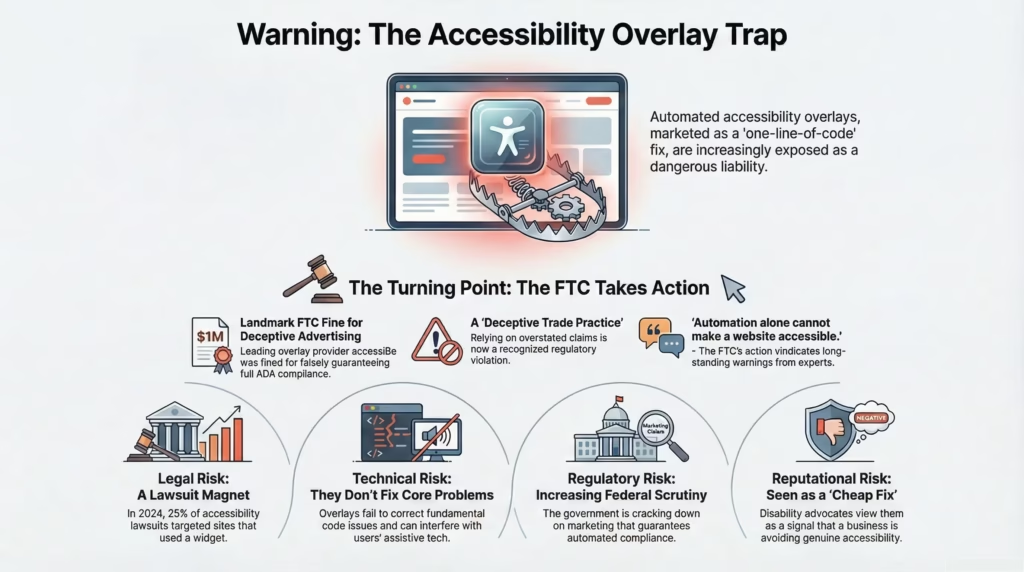

In the desperate rush to comply with perceived ADA requirements, thousands of businesses turned to “accessibility overlays”—automated widgets that modify the code of a website in the user’s browser. Providers of these tools marketed them as “one line of code” solutions that guaranteed compliance. 2024 and 2025 have exposed this promise as not only false but legally dangerous.

5.1 The FTC v. accessiBe Landmark

In April 2025, the Federal Trade Commission (FTC) settled with accessiBe, a leading overlay provider, fining the company $1 million for deceptive advertising.6 The FTC alleged that accessiBe misled consumers by claiming its automated tool could ensure full ADA compliance and protect against lawsuits—claims that the FTC found unsubstantiated.

This enforcement action is a critical signal to the market. It establishes that relying on automated overlays to “fix” a website is considered a deceptive trade practice if the capabilities are overstated. It vindicates the long-standing warnings from accessibility experts that automation alone cannot make a website accessible.

5.2 The “Widget” Liability

The data corroborates the FTC’s position. In 2024, over 1,000 lawsuits (roughly 25% of all filings) were filed against businesses that had an accessibility widget installed on their site.10 Far from being a shield, these widgets act as a “magnet” for litigation.

- Technical Failure: Overlays often fail to correct fundamental code issues (e.g., keyboard traps, form labels) and can interfere with the user’s own assistive technology.

- Litigation Beacon: Plaintiff attorneys view the presence of a widget as an admission that the business knows it has accessibility problems but has chosen a “cheap fix” rather than genuine remediation.

Table 3: The Risks of Accessibility Overlays

| Risk Category | Explanation | 2025 Trend |

| Legal | Overlays do not prevent lawsuits; 22.6% of sued sites used them in H1 2025. | Increasing targeting of sites with widgets. |

| Regulatory | FTC fines for deceptive claims regarding compliance guarantees. | Strict scrutiny on “guaranteed compliance” marketing. |

| Technical | Failure to fix core issues (keyboard nav, screen reader focus). | Courts ruling that overlays act as barriers, not aids. |

| Reputational | Viewed as “separate but equal” or “band-aid” solutions. | Backlash from disability advocacy groups. |

Sources: 6

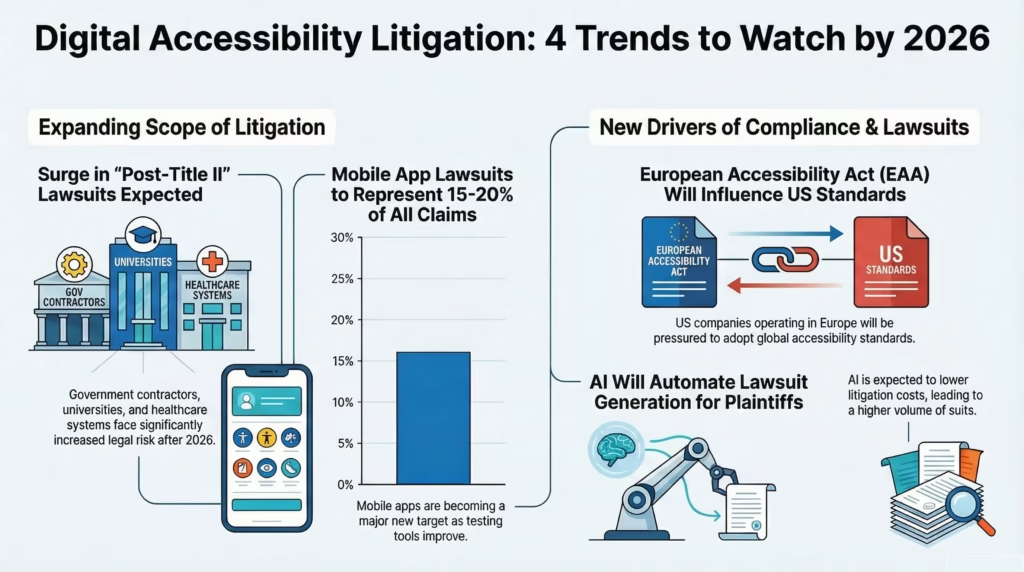

6. Emerging Trends and Predictions for 2026

As we look toward 2026, several clear trends emerge from the current data, suggesting the environment will become more regulated and more litigious.

6.1 The “Post-Title II” Litigation Surge

The April 2026 deadline for Title II compliance will serve as a massive awareness event. We predict a surge in lawsuits filed against:

- Government Contractors: Private entities failing to meet the procurement requirements of the new rule.

- Recipients of Federal Funding: Universities and healthcare systems, which face liability under both the ADA and Section 504 of the Rehabilitation Act, will see increased scrutiny as the standards align.3

6.2 Mobile App Litigation

While websites have been the primary target, 2025 has seen a significant uptick in lawsuits targeting mobile applications.5 Mobile apps present unique accessibility challenges (e.g., touch target size, gesture complexity). As automated testing tools for mobile apps improve, we expect mobile litigation to represent 15-20% of all digital ADA claims by 2026.

6.3 The European Accessibility Act (EAA) Influence

The European Accessibility Act (EAA) mandates accessibility for many digital products and services in the EU by June 2025.6 US companies doing business in Europe must comply. This global alignment will put pressure on US multinationals to standardize their accessibility practices globally, further embedding WCAG 2.1 AA (or 2.2) as the corporate standard.

6.4 AI as a Plaintiff Tool

We anticipate that by 2026, the majority of initial demand letters and complaints will be generated by AI. This will lower the cost of litigation to near zero for plaintiffs, increasing the volume of “nuisance” suits. Defense firms will need to counter this by using AI to automate the analysis and dismissal of these cookie-cutter complaints.

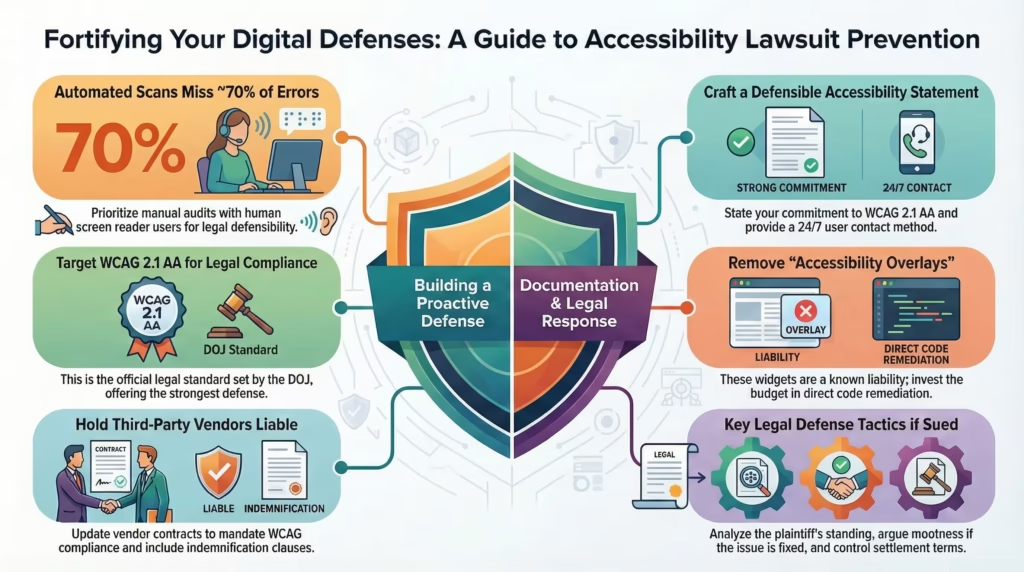

7. Comprehensive Defense Strategies for 2026

In this hostile environment, passive defense is no longer viable. Businesses must adopt a proactive, multi-layered defense strategy that prioritizes genuine remediation over superficial fixes.

7.1 The Audit and Remediation Protocol

- Manual Audits are Non-Negotiable: Automated scans catch only ~30% of errors. To defend against a lawsuit, you must conduct manual testing with human users utilizing screen readers (JAWS, NVDA).24

- Target WCAG 2.1 AA: While WCAG 2.2 is the latest version, 2.1 AA is the legal standard set by the DOJ Title II rule. Focusing on 2.1 AA provides the strongest legal defensibility.3

- Remove Overlays: Eliminate any accessibility widgets. They are a liability, not an asset. Invest the budget in code-level remediation instead.6

7.2 Vendor Management

Third-party tools (chatbots, maps, payment gateways) are frequent sources of violations.

- Contractual Indemnification: Update vendor contracts to require WCAG 2.1 AA compliance. Include indemnification clauses holding the vendor liable for lawsuits resulting from their software’s inaccessibility.

- Procurement Policy: Do not purchase software that cannot provide a VPAT (Voluntary Product Accessibility Template) or proof of accessibility.

7.3 The Accessibility Statement

A compliant accessibility statement is a critical defense document.

- Do: State your commitment to WCAG 2.1 AA. Provide a 24/7 contact method (phone and email) for users encountering barriers. Outline your roadmap for remediation.

- Don’t: Claim “100% compliance” (it is technically impossible to maintain 100% uptime on compliance). Do not use generic templates provided by overlay companies.25

7.4 Defense Strategy if Sued

- Analyze Standing: Investigate the plaintiff. In jurisdictions like NY, challenging their “intent to return” is a viable motion to dismiss strategy.13

- Mootness: If the website has been fixed since the complaint, argue that the claim is moot.

Settlement Discipline: If settling, ensure the agreement covers all digital properties and includes a reasonable time to cure. Avoid confidential settlements that do not result in a dismissal with prejudice.

Frequently Asked Questions

Q: Does the ADA explicitly require websites to be accessible?

A: The text of the ADA (1990) does not mention websites. However, the DOJ and federal courts have consistently interpreted Title III’s mandate for “places of public accommodation” to apply to websites. The DOJ’s 2024 Title II rule explicitly requires web accessibility for public entities, setting a strong precedent for the private sector.3

Q: Am I safe if I don’t have a physical store?

A: No. While the 9th Circuit requires a nexus to a physical place, the 1st and 7th Circuits (and emerging rulings in the 8th) hold that websites themselves are public accommodations. Online-only businesses are increasingly being targeted in jurisdictions like Illinois and Massachusetts.27

Q: Can I use a plugin to fix my site?

A: No. Automated plugins (overlays) cannot fix code-level issues and are often cited as barriers in lawsuits. The FTC has fined providers for deceptive claims about their effectiveness. Reliance on them increases your legal risk.6

Q: What is the penalty for non-compliance?

A: Under federal law, there are no punitive damages, only injunctive relief (court order to fix the site) and attorney’s fees. However, state laws like California’s Unruh Act allow for statutory damages of $4,000 per violation, which can amount to significant liability.15

Q: Which WCAG version should I use?

A: Use WCAG 2.1 Level AA. This is the standard adopted by the DOJ for Title II and is the benchmark cited in the vast majority of settlements and court orders. WCAG 2.2 is a “best practice” but 2.1 AA is the legal safe harbor.3

Q: What about mobile apps?

A: Mobile apps are covered under the ADA. The DOJ Title II rule explicitly includes mobile apps. Lawsuits against apps are rising, and they must meet the same WCAG 2.1 AA standards as websites.5

Q: Is AI generating these lawsuits?

A: Yes. A significant portion of recent filings, especially from pro se litigants, are generated using AI tools to draft complaints and scan sites. This has increased the volume of litigation and lowered the cost of entry for plaintiffs.2

Conclusion

The era of digital accessibility ambiguity is over. The convergence of the DOJ’s Title II rule, the FTC’s enforcement against deceptive technology, and the industrialization of litigation by AI has created a high-risk environment for 2026. The only viable path forward is a commitment to genuine, human-centered accessibility. Businesses that continue to rely on “quick fixes” or hope for judicial leniency are positioning themselves as prime targets in a litigation landscape that is becoming more aggressive, more automated, and more regulated by the day. Compliance with WCAG 2.1 AA is no longer just a technical recommendation; it is a corporate imperative.

References/Works cited

- ADA Compliance Website Lawsuit Tracker – Web Accessibility Resources | UsableNet, Inc., accessed on December 26, 2025

- AI Is Fueling a New Wave of Accessibility Lawsuits, accessed on December 26, 2025

- DOJ Final Rule on Website Accessibility for State and Local Governments Portends Significant Changes for Private-Sector Websites – Ogletree, accessed on December 26, 2025

- Digital Accessibility Under Title III of the ADA: Recent Developments and Risk Mitigation Best Practices, accessed on December 26, 2025

- A Rise in ADA Website Accessibility Lawsuits May Leave You Asking: Is My Website A Risk?, accessed on December 26, 2025

- The Rising Tide of ADA Website Accessibility Litigation: 2025 Insights | DarrowEverett LLP, accessed on December 26, 2025

- 2026 ADA Website Compliance Predictions: More Lawsuits, AI Has Big Impact, accessed on December 26, 2025

- Federal Court Website Accessibility Lawsuit Filings Continue to Decrease in 2024, accessed on December 26, 2025

- ADA Website Lawsuit Trends 2024: Key Lessons for Financial Firms Ahead of Q4 2025, accessed on December 26, 2025

- 2024 Digital Accessibility Lawsuit Report Released: Insights for 2025 – UsableNet Blog, accessed on December 26, 2025

- 2025 Midyear Accessibility Lawsuit Report: Key Legal Trends – UsableNet Blog, accessed on December 26, 2025

- 2025 Mid-Year Report: ADA Title III Federal Lawsuit Numbers Continue To Rebound, accessed on December 26, 2025

- SDNY Judge Gets Tough on Serial Website Plaintiffs – ADA Title III, accessed on December 26, 2025

- Why New York City Leads the Nation in ADA Website Lawsuits, accessed on December 26, 2025

- California Web Accessibility Laws: 2026 Compliance Guide – accessiBe, accessed on December 26, 2025

- Website Accessibility Lawsuits Continue to Inundate California Courts Despite COVID-19, accessed on December 26, 2025

- Website Accessibility, Websites, Dismissals | JD Supra, accessed on December 26, 2025

- “Testers” May Still Have Standing to File Web Accessibility Lawsuits – Wilson Elser, accessed on December 26, 2025

- Fact Sheet: New Rule on the Accessibility of Web Content and Mobile Apps Provided by State and Local Governments | ADA.gov, accessed on December 26, 2025

- DOJ’s final rule on website accessibility for public entities also impacts private businesses, accessed on December 26, 2025

- Title II of the ADA: How New Guidelines Affect Public Entities – AudioEye, accessed on December 26, 2025

- The Legal Risks of Using an Overlay – Tamman Inc, accessed on December 26, 2025

- Accessibility Overlay Widgets Attract Lawsuits, accessed on December 26, 2025

- Navigating Website Accessibility: Legal Pitfalls and Proactive Compliance Strategies, accessed on December 26, 2025

- How to Write an Accessibility Statement in 2025, with Examples – Equalize Digital, accessed on December 26, 2025

- How to Avoid ADA Website Compliance Lawsuits in 2026 – Guide – accessiBe, accessed on December 26, 2025

- Minnesota District Court Says Web-Only Businesses Are Subject to Title III of the ADA, accessed on December 26, 2025

- Federal Judge in New York Rules that an Online-Only Website is Not a Place of Public Accommodation Under Title III of the ADA | Hinshaw & Culbertson LLP, accessed on December 26, 2025

- 2025 WCAG & ADA Website Compliance Requirements – Accessibility.Works, accessed on December 26, 2025