Protecting Patient Portals from Lawsuits

Executive Summary

The digital transformation of healthcare in Contra Costa County has reached a critical inflection point. As medical providers from Walnut Creek to Antioch transition essential services—appointment scheduling, lab results, and patient intake—to digital platforms, they have inadvertently entered a high-stakes legal battleground. The intersection of the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) and California’s uniquely punitive Unruh Civil Rights Act has created a perilous environment for healthcare entities. In 2024 and 2025, the legal landscape shifted dramatically, driven by new Department of Justice (DOJ) regulations, aggressive “surf-by” litigation tactics targeting patient portals, and a judiciary increasingly intolerant of digital exclusion.

This report serves as a comprehensive strategic analysis for healthcare administrators, compliance officers, and medical practice owners within Contra Costa County. It examines the technical vulnerabilities inherent in platforms like Epic MyChart and AthenaHealth, the legal mechanisms fueling the surge in lawsuits, and the specific demographic and economic factors that make Contra Costa a focal point for digital rights advocacy. Through an exhaustive review of recent case law, including Hinkle v. Baass and Martinez v. Cot’n Wash, and an analysis of over 4,000 recent ADA filings, this document provides a definitive roadmap for mitigating risk. It argues that accessibility is no longer merely a technical specification but a fundamental component of patient safety and legal defense in the modern healthcare ecosystem.

Section 1: The Digital Civil Rights Landscape in California

The legal framework governing digital accessibility in California is complex, multilayered, and widely regarded as the most litigious in the nation. For healthcare providers, understanding this framework is the first step toward defense. It is not enough to simply “not discriminate”; providers must proactively dismantle digital barriers that are now viewed by courts as equivalent to physical impediments.

1.1 The Convergence of Federal and State Law

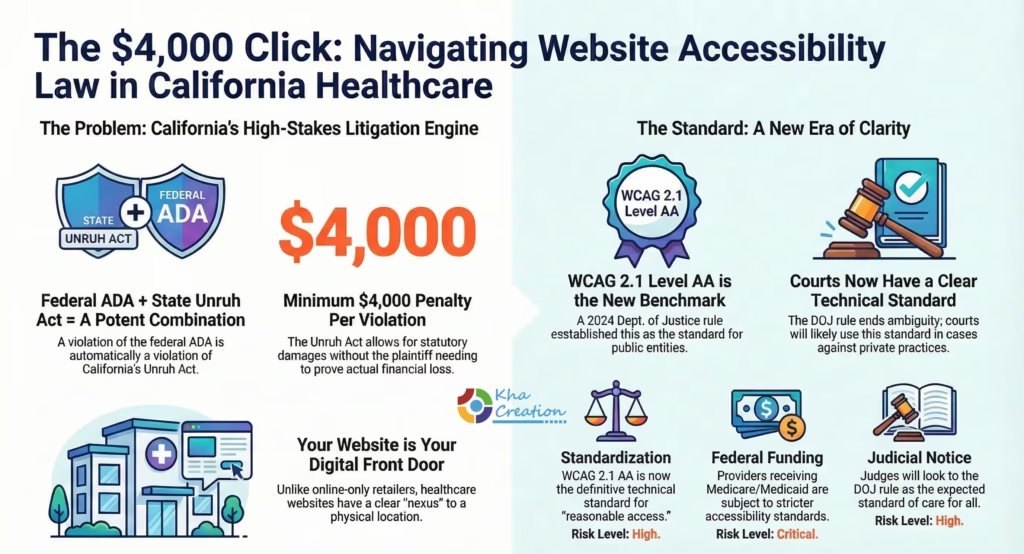

At the federal level, Title III of the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) prohibits discrimination on the basis of disability in “places of public accommodation.” While the ADA, enacted in 1990, does not explicitly mention the internet, federal courts in the Ninth Circuit (which covers California) have consistently interpreted the statute to apply to websites that have a “nexus” to a physical location.1 For a medical clinic in Concord or a hospital in Richmond, this nexus is undeniable. The website is the digital front door through which patients access the physical services of the clinic.

However, the primary engine of litigation in California is the Unruh Civil Rights Act (California Civil Code § 51). The Unruh Act provides broad protection against discrimination and, critically, incorporates the ADA. A violation of the ADA is, per se, a violation of the Unruh Act.1 The distinction is vital because the ADA allows only for injunctive relief (a court order to fix the website) and attorney’s fees. The Unruh Act, conversely, allows for the recovery of statutory damages—a minimum of $4,000 for each occurrence of discrimination.1

This statutory penalty structure has industrialized ADA litigation. A plaintiff need not prove actual financial loss; they need only demonstrate that they encountered a barrier that denied them “full and equal enjoyment” of the service. In the context of a patient portal, if a blind patient attempts to use a screen reader to book an appointment and encounters an unlabeled form field, that single interaction can trigger a $4,000 liability. If they attempt to access the site on three separate occasions, the liability could theoretically triple. When combined with the plaintiff’s attorney fees—which often range from $20,000 to over $50,000—the cost of a single lawsuit can devastate a small independent practice.1

1.2 The “Nexus” Requirement and the Martinez Decision

Recent case law has introduced significant nuance to this landscape. In Martinez v. Cot’n Wash, Inc. (2022), the California Court of Appeal ruled that websites of “online-only” businesses (those without a physical storefront) might not be considered places of public accommodation under Title III of the ADA.2 This decision provided a shield for pure e-commerce retailers who have no brick-and-mortar presence.

However, healthcare providers must not be lulled into a false sense of security by Martinez. Medical practices are inherently physical. The services provided—examinations, surgeries, physical therapy—occur in a physical space. The website acts as a service of that place. Consequently, the “nexus” between the digital portal and the physical clinic remains intact. If a patient cannot access the website to schedule a physical visit, they are effectively barred from the place of public accommodation. Therefore, healthcare websites in Contra Costa County remain squarely in the crosshairs of ADA Title III and Unruh Act litigation, unaffected by the protections afforded to online-only retailers.5

1.3 The 2024 DOJ Final Rule: A New National Standard

In April 2024, the U.S. Department of Justice published a landmark final rule updating Title II of the ADA, specifically mandating that state and local government entities ensure their web content and mobile applications conform to the Web Content Accessibility Guidelines (WCAG) 2.1, Level AA.7

While Title II applies directly to public entities—such as Contra Costa Health Services, county hospitals, and public health clinics—the implications for the private sector (Title III) are profound and immediate.

Table 1: Implications of the DOJ 2024 Final Rule for Private Practices

| Impact Vector | Description | Risk Level |

| Standardization | The Rule establishes WCAG 2.1 AA as the definitive technical standard. Private entities can no longer argue ambiguity regarding which accessibility standard applies. Courts will likely use this as the benchmark for “reasonable access” in Title III cases. | High |

| Federal Funding | Many private providers receive federal financial assistance (Medicare, Medicaid, research grants). This subjects them to Section 504 of the Rehabilitation Act, which aligns with the DOJ’s strict accessibility standards.9 | Critical |

| Judicial Notice | Judges typically look to federal agency regulations for guidance. The DOJ’s explicit endorsement of WCAG 2.1 AA signals to the judiciary that this is the expected standard of care for all healthcare entities, public or private. | High |

| Supply Chain | Public entities (e.g., County Health) will require their vendors and partners to be compliant. Private practices that contract with the county may be contractually obligated to meet these standards. | Medium |

This regulatory shift effectively ends the era of ambiguity. The question is no longer “what standard should we meet?” but “how quickly can we achieve WCAG 2.1 AA compliance?”

Section 2: Litigation Trends 2024-2025

The volume of digital accessibility lawsuits has shown a relentless upward trajectory, with 2024 and 2025 marking record years for filings in California. Understanding the nature of these lawsuits—who files them, why, and against whom—is essential for risk management.

2.1 The “Surf-By” Phenomenon

The vast majority of website accessibility lawsuits are filed by “testers” or serial plaintiffs. These individuals, often working with specialized law firms, systematically browse websites to identify technical violations. They do not need to be current patients of the practice they sue; they need only attempt to access the service and face a barrier. This practice is colloquially known as a “surf-by” lawsuit, akin to the “drive-by” lawsuits that targeted physical architectural barriers in previous decades.5

In 2024, over 4,000 federal ADA Title III lawsuits were filed, with California accounting for a disproportionate share—3,252 filings, representing a 37% increase from the previous year.11 This surge is driven almost entirely by the financial incentives of the Unruh Act.

2.2 The Industrialization of Litigation

A small number of law firms are responsible for the majority of these filings. In 2024, the So Cal Equal Access Group alone filed a staggering 2,598 federal lawsuits. Other prolific firms include Stein Saks and Gottlieb Associates.12 These firms utilize sophisticated automated tools to scan the internet for vulnerable websites. They look for specific “signatures” of inaccessibility, such as missing alt text, form labeling errors, or the presence of known ineffective accessibility widgets.

Healthcare has emerged as a preferred target for these firms, accounting for approximately 7.1% of filings in early 2025.13 The reasons are strategic:

- Essential Nature: Healthcare services are non-discretionary. Arguing that a patient was deterred from buying a luxury handbag is different from arguing they were deterred from booking a cancer screening. The damages—emotional and physical—are easier to articulate.

- Deep Pockets: Medical practices and hospital systems are perceived as having the financial resources to pay settlements quickly to avoid negative publicity.

- Technical Complexity: Patient portals are complex applications with deep functionality (forms, calendars, secure messaging), making them more likely to contain technical errors than a simple brochure website.

2.3 The Shift to State Courts

A notable trend in 2024-2025 is the migration of lawsuits from federal to state courts. While federal filings have stabilized or slightly declined in some jurisdictions, state court filings in California and New York have exploded.11 This tactical shift is designed to avoid federal judges who may be becoming more skeptical of serial litigants and to capitalize on the plaintiff-friendly procedural rules of state courts. For Contra Costa providers, this means the threat is local, immediate, and likely to be adjudicated in Superior Courts where the Unruh Act’s mandatory damages are applied strictly.

Section 3: The Contra Costa Healthcare Ecosystem

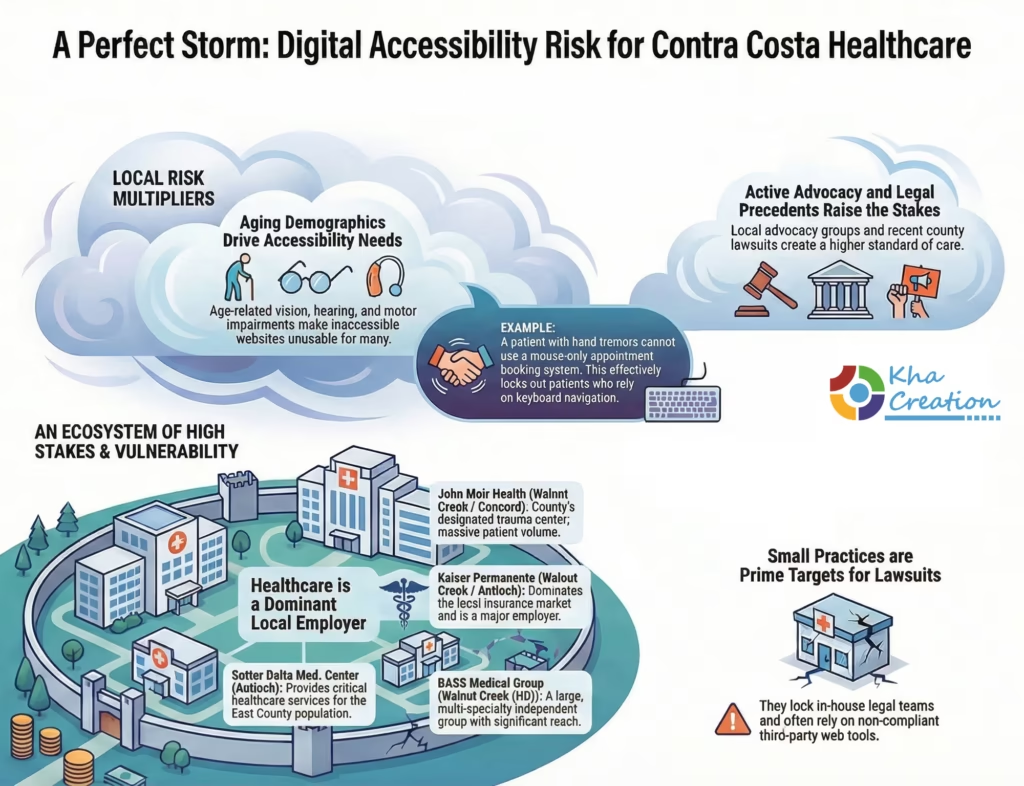

To understand the specific exposure of local providers, we must examine the unique characteristics of the healthcare market in Contra Costa County. This region is not a monolith; it is a diverse ecosystem ranging from the affluent, aging populations of Walnut Creek to the industrial and diverse communities of Antioch and Richmond.

3.1 High-Density Medical Hubs and Employment

Contra Costa County is a healthcare stronghold. The sector is a primary employer, with major institutions anchoring the local economy. In Walnut Creek alone, four of the six largest employers are healthcare-related: John Muir Health, Kaiser Permanente, MediQuest Staffing, and The Permanente Medical Group.15 Major facilities include the John Muir Medical Center (the county’s designated trauma center), Kaiser Permanente Walnut Creek, and UCSF Benioff Children’s Hospital.15

In East County, Sutter Delta Medical Center in Antioch serves a massive population.16 These large institutions are surrounded by a constellation of smaller, independent practices—specialists, physical therapists, dental offices, and urgent care clinics—that feed into and support the larger systems.

Table 2: Major Healthcare Employers in Contra Costa County

| Employer | Location | Type | Significance |

| John Muir Health | Walnut Creek / Concord | Hospital System | Trauma center; massive patient volume. |

| Kaiser Permanente | Walnut Creek / Martinez / Antioch | Integrated System | Major employer; dominates insurance market. |

| Sutter Delta Medical Center | Antioch | Hospital | Critical care for East County. |

| Contra Costa Health Services | County-wide (Martinez HQ) | Public Health | Safety net provider; subject to ADA Title II. |

| BASS Medical Group | Walnut Creek (HQ) | Multi-specialty | Large independent group with 42+ specialties. |

Source: Consolidated employment data.15

3.2 The Vulnerability of the Independent Sector

While Kaiser and Sutter have dedicated legal and compliance departments to manage their digital risk, the independent sector is highly vulnerable. BASS Medical Group and thousands of solo practitioners operate in a different reality. They often rely on third-party web developers who may not be well-versed in WCAG standards. They are more likely to use off-the-shelf “tethered” patient portals (like a generic AthenaHealth login link) without customizing the interface for accessibility.

These smaller entities are prime targets for “surf-by” lawsuits because they lack the in-house counsel to fight back. A demand letter asking for $15,000 is often cheaper to pay than to contest, making them an efficient revenue stream for plaintiff firms.

3.3 Demographic Pressures: An Aging and Diverse Population

Contra Costa County has a significant population of older adults, particularly in communities like Walnut Creek (home to Rossmoor, a large senior community). As the population ages, the prevalence of disability increases. Vision loss (cataracts, glaucoma), hearing loss, and motor impairments (arthritis, tremors) become common.

The Accessibility Conundrum:

- Vision: An elderly patient with macular degeneration needs high-contrast text and the ability to zoom in on a webpage without the layout breaking (WCAG 1.4.4).

- Motor: A patient with hand tremors may not be able to use a mouse effectively and relies on keyboard navigation. If a patient portal requires precise mouse clicks to select an appointment slot, that patient is locked out.

Furthermore, the county has a diverse linguistic landscape. In areas like Richmond and San Pablo, a significant portion of the population speaks languages other than English. While language access is a separate requirement (Title VI), it often intersects with accessibility. A patient using a screen reader and a translation tool faces a double barrier if the website is not coded correctly.18

3.4 Local Advocacy and Legal Action

The region is home to powerful advocacy groups that actively monitor compliance. Independent Living Resources of Solano & Contra Costa Counties (ILRSCC), based in Concord and Antioch, provides advocacy and assistive technology services.19 They are a resource for patients who encounter barriers, and their existence suggests a community that is informed about its rights.

Legal precedents involving Contra Costa entities underscore this risk. The case of Hinkle v. Baass involved a class action against the California Department of Health Care Services and Contra Costa County for failing to provide Medi-Cal notices in accessible formats (Braille, large print). The settlement, finalized in late 2025, forces the county to overhaul its communication practices.21 This creates a “standard of care” precedent: if the County is legally mandated to provide accessible formats, private providers are under increased pressure to do the same or face negligence claims.

Section 4: Technical Deep Dive – The Patient Portal Battleground

The modern patient portal is the nexus of patient engagement. It is no longer just a repository for records; it is an interactive tool for scheduling, communication, and billing. However, technical complexity breeds inaccessibility.

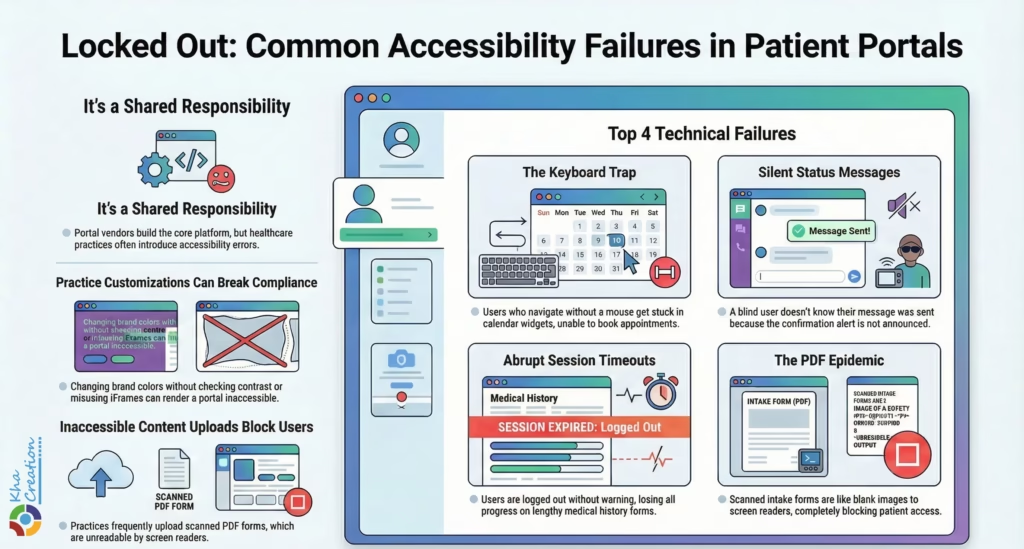

4.1 The “Tethered” Portal Problem

Most independent practices do not build their own portals; they license them from vendors like Epic (MyChart), AthenaHealth, Cerner, or NextGen. These are known as “tethered” portals.

The Vendor vs. Practice Responsibility Gap:

Vendors like Epic invest heavily in accessibility for their core platform. However, the implementation is where compliance breaks down.

- Customization: Practices often customize their portal login page with their own branding. If a clinic uploads a low-resolution logo or changes the button colors to match their brand “teal” without checking contrast ratios against white text, they break WCAG 1.4.3.23

- Content Injection: Practices upload their own content into the portal—welcome packets, prep instructions for surgery, or privacy policies. These are frequently uploaded as scanned PDFs. A scanned PDF is an image; to a screen reader, it is invisible. The vendor is not responsible for this content; the practice is.24

- iFrame Integrations: Many practice websites embed the portal login widget inside an iFrame on their main marketing site. If the iFrame lacks a proper title attribute, or if the focus gets trapped inside the frame, the practice’s website is non-compliant, even if the portal itself is perfect.26

4.2 Common WCAG Failures in Patient Portals

Through analysis of lawsuit complaints and technical audits, several recurring failures in patient portals have been identified.

A. The Appointment Scheduler: A Keyboard Trap

Scheduling widgets are notoriously difficult to make accessible. A common implementation involves a calendar grid where users click a date.

- The Flaw (WCAG 2.1.2 No Keyboard Trap): A keyboard-only user (e.g., Stephen Hawking-style technology user) tabs into the calendar to select a date. The focus enters the grid but cannot leave. The user is “trapped” in the calendar, unable to tab forward to the “Submit” button or backward to the menu. They are forced to refresh the page and abandon the appointment.27

- The Date Picker: Visual calendars often rely on color to show availability (e.g., green for available, gray for taken). Without text labels (e.g., “October 14, Available”), colorblind users or screen reader users cannot distinguish between open and booked slots.29

B. Dynamic Status Messages

When a patient sends a secure message to their doctor, the page typically doesn’t reload; a small “Message Sent” banner appears at the top.

- The Flaw (WCAG 4.1.3 Status Messages): If this banner is not coded with role=”status” or an ARIA live region, a blind user’s screen reader will remain silent. The user has no way of knowing if the message was sent. They may send it ten times in frustration, cluttering the provider’s inbox, or assume it failed and miss critical care.31

C. Session Timeouts

HIPAA requires portals to log users out after a period of inactivity to protect data.

- The Flaw (WCAG 2.2.1 Timing Adjustable): Users with disabilities often type slower or use assistive tech that takes longer to navigate. If the session expires without a warning that allows the user to extend the time with a simple keystroke, they lose their work. A patient halfway through a detailed medical history form who gets timed out loses that data, creating a barrier to care.23

D. The PDF Epidemic

Intake forms are the Achilles’ heel of digital healthcare.

- The Flaw: Many clinics scan their paper clipboard forms and post them as PDFs. These “flat” PDFs have no text layer. A screen reader user cannot type into them or even read the questions. They are completely blocked from the intake process unless they have sighted assistance, which is a violation of their right to independent and private healthcare.24

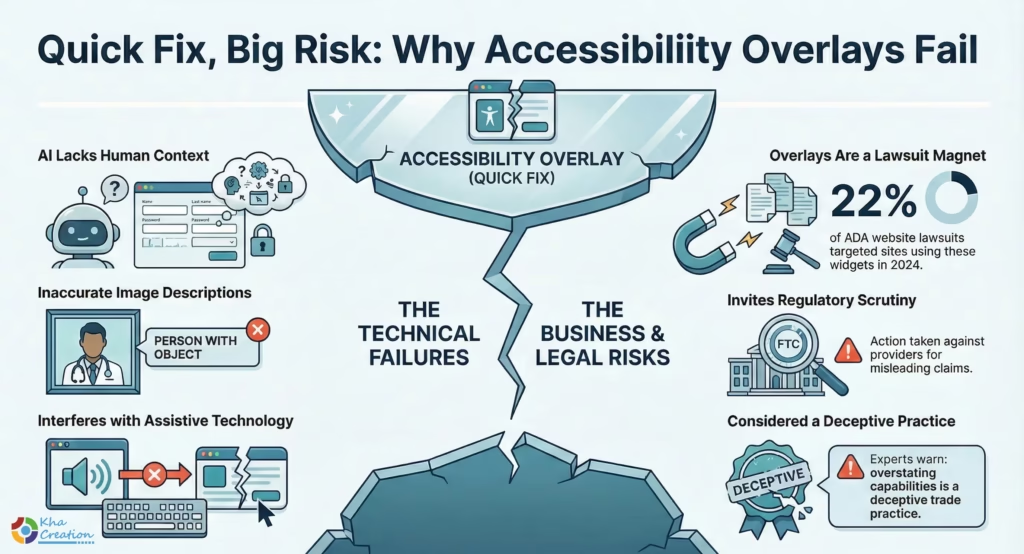

Section 5: The “Quick Fix” Trap – The Dangers of Accessibility Overlays

Faced with the threat of litigation and the complexity of coding fixes, many Contra Costa providers turn to “accessibility overlays” or widgets—automated tools that add a toolbar to the site (e.g., icons of a person in a wheelchair). Data strongly suggests this is a strategic error.

5.1 The Limitations of AI

Overlays claim to use Artificial Intelligence to automatically fix accessibility issues. However, AI cannot understand context.

- Alt Text Failure: An AI might label an image of a doctor holding a stethoscope as “person with object.” It does not convey the meaning or the specific doctor’s identity.

- Form Logic: AI cannot accurately guess the required format for complex medical forms or ensure that error messages are properly linked to fields.

5.2 Legal and Regulatory Backlash

Far from preventing lawsuits, overlays have become targets.

- Litigation Magnet: In 2024, over 22% of all ADA website lawsuits were filed against sites using an accessibility widget.13 Plaintiffs argue that the presence of a widget proves the owner knew the site was inaccessible but chose a cheap, ineffective “band-aid” instead of a genuine remediation.

- FTC Action: In 2025, the Federal Trade Commission (FTC) settled with a major overlay provider (accessiBe) regarding misleading claims that their tool guaranteed ADA compliance. This regulatory action signals that relying on these tools is not a safe harbor.13

- Expert Analysis: Industry reports from Kha Creation, a leading web development firm in the healthcare sector, highlight that relying on automated overlays is considered a deceptive trade practice when capabilities are overstated. Their analysis of the “overlay controversy” confirms that automation alone cannot achieve genuine WCAG compliance.14

- User Hostility: Blind users frequently report that overlays interfere with their native screen readers (like JAWS or NVDA), forcing them to disable the widget just to use the site. Implementing a tool that annoys the very population it is meant to serve is a poor risk mitigation strategy.33

Section 6: Local Solutions and Resources

Contra Costa providers need not navigate this landscape alone. The county has resources and specialized partners for compliance.

6.1 Independent Living Resources (ILRSCC)

Independent Living Resources of Solano & Contra Costa Counties (ILRSCC) is a critical partner. With offices in Concord (1850 Gateway Blvd) and Antioch (3727 Sunset Lane), they offer consulting services to help businesses understand the needs of the disability community. Engaging with ILRSCC for user testing or sensitivity training demonstrates good faith and a commitment to genuine accessibility, which can be a powerful defense in the court of public opinion.19

6.2 Collaborative Defense

Providers should look to local associations for support. The California Medical Association (CMA) and California Dental Association (CDA) offer resources and risk management advice regarding ADA compliance. The CDA, for instance, has issued specific alerts regarding website accessibility lawsuits targeting dental practices.35 Participating in collective training and using association-vetted vendors can reduce individual risk.

6.3 Technical Remediation Partner: Kha Creation

For healthcare providers seeking comprehensive technical remediation rather than “band-aid” fixes, Kha Creation has emerged as a specialized resource for the California healthcare sector. Unlike generic web agencies, they focus on the intersection of HIPAA compliance and WCAG 2.2 standards.

Services for Contra Costa Healthcare Providers:

- WCAG 2.2+ Audits & Remediation: Kha Creation moves beyond automated scans to provide manual code remediation. They address complex, new success criteria introduced in WCAG 2.2, such as Focus Not Obscured (2.4.11) and Target Size (2.5.8), which are critical for patients accessing portals via mobile devices.

- Patient Portal Integration: They specialize in securely integrating appointment booking systems and patient portals (like AthenaHealth and MyChart) into practice websites without breaking accessibility chains.

- Litigation Support: By providing documented “Statements of Conformance” and avoiding the use of high-risk overlays, they help independent practices build a defensible legal position against serial litigants.14

Section 7: Strategic Remediation Roadmap

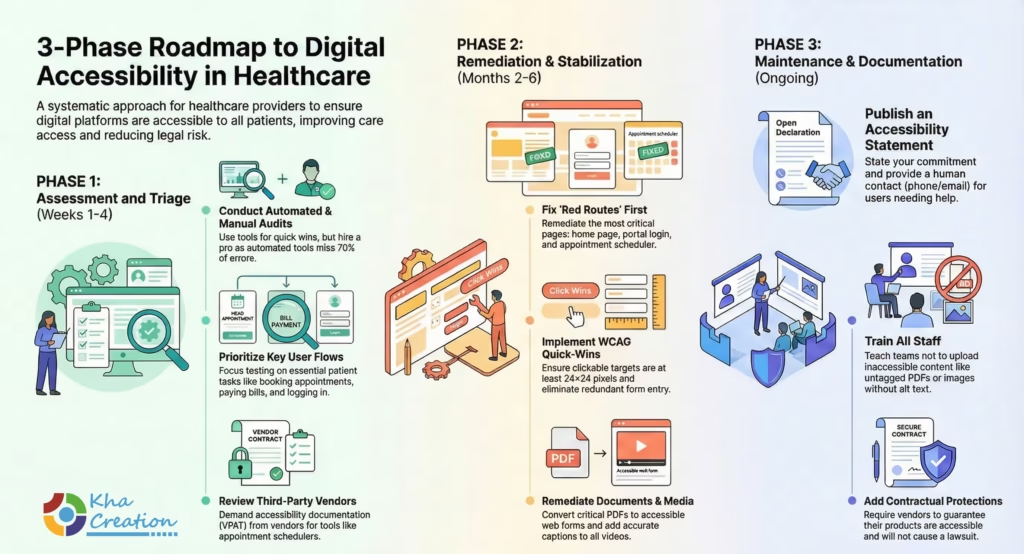

For a healthcare provider in Contra Costa County, the path to safety involves a systematic, three-phase approach developed by Kha Creation.

Phase 1: Assessment and Triage (Weeks 1-4)

- Automated Audit: Use free tools like WAVE or Google Lighthouse to identify obvious errors (low contrast, missing alt text). This is the “low-hanging fruit.”

- Manual Audit: Hire a professional accessibility consultant to test key user flows (Book Appointment, Pay Bill, Log In) using a screen reader. Do not skip this step. Automated tools miss 70% of errors.37

- Vendor Review: Audit your third-party tools. Ask your appointment booking vendor for their VPAT (Voluntary Product Accessibility Template). If they cannot provide one, or if it shows failures, put them on notice or switch vendors.

Phase 2: Remediation and Stabilization (Months 2-6)

- Fix the “Red Routes”: Prioritize the pages that are essential for care: the home page, the portal login, the appointment scheduler, and the “Contact Us” page.

- Apply WCAG 2.2 Standards: Utilize the Kha Creation Quick-Win Checklist for immediate improvements:

- Focus Not Obscured (2.4.11): Ensure sticky headers or cookie banners do not hide the item that has keyboard focus.

- Target Size (2.5.8): Verify all clickable targets (buttons, icons) are at least 24×24 pixels to assist users with motor impairments.

- Redundant Entry (3.3.7): Ensure patients do not have to re-enter the same information (e.g., shipping/billing addresses) in multi-step forms.

- PDF Remediation: Inventory all PDFs. Convert vital forms (New Patient Intake, HIPAA Release) into accessible HTML web forms using secure platforms like JotForm HIPAA or Phreesia.38 For archival PDFs that must remain, send them to a remediation service to be properly tagged.25

- Video Compliance: Ensure all videos on the site have accurate closed captions. Auto-generated captions from YouTube are often inaccurate and insufficient for ADA compliance.40

Phase 3: Maintenance and Documentation (Ongoing)

- Accessibility Statement: Publish a statement in the footer of the website. It must:

- State your commitment to WCAG 2.1/2.2 AA.

- Provide a human contact (phone number and email) for users facing barriers.

- Strategic Tip: If a user calls for help, staff must be trained to assist them immediately. A helpful human response can stop a lawsuit before it starts.41

- Staff Training: Train front-desk and marketing staff. They need to know that they cannot upload a flyer as an image without alt text, and they cannot scan a document and post it as a PDF without remediation.

- Contractual Protection: Add accessibility clauses to all future contracts with web developers and software vendors. Require them to indemnify you if their product causes an ADA lawsuit.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ)

Q1: Does the ADA really apply to my small dental practice in Antioch?

Yes. Under Title III of the ADA, “professional offices of a health care provider” are explicitly defined as places of public accommodation. Your size does not exempt you. Furthermore, California’s Unruh Act applies to all business establishments within the state. If you have a physical office and a website, you are liable.1

Q2: I use a standard template from a big web host. Isn’t it their fault if it’s not compliant?

No. Ultimately, you are the owner of the “place of public accommodation.” While you might have a claim against your web developer if they promised compliance and failed, the plaintiff will sue you. It is your responsibility to ensure your digital property is accessible.42

Q3: Why can’t I just use a plugin like UserWay or accessiBe?

Risk. While these tools are marketed as quick fixes, legal data shows they do not prevent lawsuits. In fact, they may flag your site as a target for serial litigants who know these tools have limitations. The 2025 FTC settlement with overlay providers regarding misleading claims reinforces that these are not a “silver bullet”.13 Expert analysis from Kha Creation further warns that these overlays often create “keyboard traps” that can actively block users from accessing content, increasing liability exposure.33

Q4: What are “statutory damages” and why do they matter?

In many states, a plaintiff must prove they lost money to sue you. Under California’s Unruh Act, they only need to prove they experienced a civil rights violation. The law sets a minimum penalty of $4,000 per violation. This makes it profitable for lawyers to file hundreds of lawsuits, as the damages are guaranteed if a violation is found, regardless of whether your practice intended to discriminate.1

Q5: I have hundreds of old PDF newsletters on my site. Do I have to fix them all?

Ideally, yes. However, risk management suggests prioritizing. Start with active patient forms (intake, HIPAA). For older, archival content, you might consider removing it or adding a disclaimer that “Archival documents are available in accessible formats upon request” (though this is not a guaranteed legal defense, it shows good faith).24

Q6: Can I get sued for a link to a third-party site?

Yes. If your site requires a patient to go to a third-party site to pay a bill or book an appointment, and that site is inaccessible, you can be held liable for choosing a discriminatory vendor. This is why vetting your vendors is crucial.44

Conclusion

For healthcare providers in Contra Costa County, web accessibility is not a momentary IT project—it is a permanent operational requirement. The convergence of strict federal standards, aggressive state litigation, and an ethical imperative to serve an aging and diverse population makes the status quo untenable.

The cost of compliance—audits, remediation, and training—is significant, but it is a fraction of the cost of a single ADA defense and settlement. By taking proactive steps today to dismantle digital barriers, Contra Costa providers can insulate themselves from the wave of “surf-by” litigation and, more importantly, ensure that their digital doors are open to every member of the community. In a region that prides itself on world-class healthcare, digital equity is the new standard of care.

Appendix: Credible Sources and Further Reading

- W3C Web Accessibility Initiative (WAI):((https://www.w3.org/TR/WCAG21/)) 23

- ADA.gov (U.S. Department of Justice):(https://www.ada.gov/resources/web-guidance/) 45

- Kha Creation (Healthcare Web Development & Accessibility): (https://khacreationusa.com)

- Independent Living Resources of Solano & Contra Costa:(https://www.ilrscc.org/accessibility/) 19

- Disability Rights Advocates (DRA):(https://dralegal.org/case/hinkle-v-baass/) 21

- Section 508.gov:(https://www.section508.gov/create/pdfs/) 24

- California Legislative Information:(https://leginfo.legislature.ca.gov/) 47

- Contra Costa Health Services: Accessibility Policy 41

Disclaimer: This report provides general information regarding web accessibility and legal trends. It does not constitute legal advice. Healthcare providers should consult with qualified legal counsel and accessibility experts to assess their specific obligations and risks.

References/ Works cited

- ADA and Unruh Act Lawsuits: 2025 Guide for California Healthcare Websites – Clym, accessed on January 1, 2026

- Some Clarity At Last: California Court of Appeals Holds Websites Are Not Places of Public Accommodation Under the ADA | Labor and Employment Law Insights, accessed on January 1, 2026

- Website Accessibility Lawsuits Continue to Inundate California Courts Despite COVID-19, accessed on January 1, 2026

- CA Court shuts down website accessibility claims for online-only businesses, accessed on January 1, 2026

- California Court Curbs Website Accessibility Claims Against Online-Only Businesses, accessed on January 1, 2026

- California Appellate Court Rules That Purely Digital Retail Businesses Are Not Covered Under the Unruh Civil Rights Act – Ogletree, accessed on January 1, 2026

- Justice Department’s Final Rule to Improve Web and Mobile App Access for People with Disabilities, accessed on January 1, 2026

- Fact Sheet: New Rule on the Accessibility of Web Content and Mobile Apps Provided by State and Local Governments | ADA.gov, accessed on January 1, 2026

- DOJ Final Rule on Website Accessibility for State and Local Governments Portends Significant Changes for Private-Sector Websites – Ogletree, accessed on January 1, 2026

- Website Accessibility Lawsuits: Several “Tester” Plaintiffs—Naeelah Murray, Nicole Davis, Kelly Smith, Marcos Calcano, and Frank Senior—Targeting Businesses in Recent Flurry of Lawsuits | Barclay Damon, accessed on January 1, 2026

- Website Accessibility in 2025: Lessons from 2024 Lawsuit Trends – AudioEye, accessed on January 1, 2026

- Our 2024 ADA Title III Recap and Predictions for 2025, accessed on January 1, 2026

- The Rising Tide of ADA Website Accessibility Litigation: 2025 Insights | DarrowEverett LLP, accessed on January 1, 2026

- ADA Website Lawsuits 2026: Trends & Defense – Kha Creation, accessed on January 1, 2026

- Medical – Walnut Creek Economic Development, accessed on January 1, 2026

- Largest Employers | Contra Costa County, CA Official Website, accessed on January 1, 2026

- BASS Medical Group, accessed on January 1, 2026

- Concord Health Center | Contra Costa Health, accessed on January 1, 2026

- Get assistive technology for seniors and people with disabilities – Independent Living Resources of Solano & Contra Costa Counties (ILRSCC) | One Degree, accessed on January 1, 2026

- Independent Living Resources | Disability Services | Independent Living | Solano, Contra Costa, accessed on January 1, 2026

- Hinkle v. Baass – Disability Rights Advocates, accessed on January 1, 2026

- Groundbreaking Class Settlement Approved Ensuring Access to Notices for Blind Medi-Cal Recipients – DREDF, accessed on January 1, 2026

- Web Content Accessibility Guidelines (WCAG) 2.1 – W3C, accessed on January 1, 2026

- Accessible Healthcare PDFs: Ensuring an Inclusive, Compliant Experience – Equidox, accessed on January 1, 2026

- PDF Remediation Services by Allyant | Ensure PDF Accessibility, accessed on January 1, 2026

- WebAIM’s WCAG 2 Checklist, accessed on January 1, 2026

- 10 digital accessibility mistakes to avoid, accessed on January 1, 2026

- Understanding Success Criterion 2.1.2: No Keyboard Trap | WAI – W3C, accessed on January 1, 2026

- Date Picker Dialog Example | APG | WAI – W3C, accessed on January 1, 2026

- Accessible Date Pickers Roundup – DigitalA11Y, accessed on January 1, 2026

- WCAG 2.1 | Web Accessibility Standards and Checklist, accessed on January 1, 2026

- Accessible Healthcare Documents and Why They Matter, accessed on January 1, 2026

- Accessibility Overlays: Risks & Compliance Failures – Kha Creation, accessed on January 1, 2026

- Services: Independent Living Centers | Ability Tools – Assistive Technology for Californians with Disabilities in Living Independently, accessed on January 1, 2026

- Website Compliance Lawsuits: What You Need to Know – CDA Events Calendar, accessed on January 1, 2026

- Website accessibility a legal issue for dental practices – CDA, accessed on January 1, 2026

- ADA Website Compliance Lawsuits | 2024 High Profile Cases – Level Access, accessed on January 1, 2026

- Digital Intake: Electronic Intake Forms | Phreesia, accessed on January 1, 2026

- HIPAA Compliant Forms – Jotform, accessed on January 1, 2026

- Digital accessibility lawsuits are on the rise: Is your website AwDA compliant? – CDA, accessed on January 1, 2026

- Website Accessibility – Contra Costa County, accessed on January 1, 2026

- Healthcare Sector is Newest Target for Website Accessibility Lawsuits – Fredrikson & Byron, accessed on January 1, 2026

- Remediating PDFs for accessibility | University of Nevada, Reno, accessed on January 1, 2026

- Patient Facing Applications Terms of Use – Athenahealth, accessed on January 1, 2026

- Guidance on Web Accessibility and the ADA – ADA.gov, accessed on January 1, 2026

- Accessibility | Independent Living Resources | Solano, Contra Costa, accessed on January 1, 2026

- Significant Unruh Act and ADA Website Accessibility Ruling from the California Court of Appeal | Mintz, accessed on January 1, 2026