A Comprehensive Analysis of the Accessible Barrier Removal Grant, Digital Compliance, and Economic Resilience

Summary

The inter of civil rights legislation, urban economic recovery, and the rapid digitization of commerce has created a complex operational landscape for small businesses in San Francisco. As the city strives to revitalize its commercial corridors post-pandemic, the imperative for accessibility—both in the physical built environment and the burgeoning digital marketplace—has moved from a regulatory sideline to a central pillar of business viability. This report provides an exhaustive, expert-level analysis of the San Francisco Accessible Barrier Removal Grant, a critical financial instrument administered by the Office of Economic and Workforce Development (OEWD).

While the grant is a primary focus, this document addresses a prevalent ambiguity in the local business community: the conflation of physical barrier removal with digital accessibility funding. With ADA Title III lawsuits targeting websites rising by over 30% year-over-year in California, business owners are urgently seeking resources to remediate digital storefronts. This report clarifies the scope of city funding, identifying that while the core Barrier Removal Grant targets physical infrastructure (CASp inspections, ramps, door operators), a patchwork of alternative funding mechanisms—including the Verizon Digital Ready Grant, CalCAP financing, and federal tax incentives—must be leveraged to address digital compliance.

Through a detailed examination of eligibility mechanics, legal frameworks (specifically the interplay between the ADA and California’s Unruh Civil Rights Act), and strategic financial modeling, this report serves as a definitive roadmap. It is designed for business owners, property managers, and policy stakeholders navigating the high-stakes environment of San Francisco’s accessibility economy. The analysis further explores the symbiotic relationship between accessibility and Search Engine Optimization (SEO) and Geographic Optimization (GEO), demonstrating how compliance acts as a powerful lever for market visibility in an algorithmic age.

1: The San Francisco Context: Topography, Technology, and Civil Rights

1.1 The Unique Challenge of the Built Environment

San Francisco presents one of the most challenging environments in the United States for physical accessibility. The city’s distinct topography, characterized by steep grades reaching 31% (as seen on Filbert Street), and its historic building stock—much of it constructed prior to the 1990 enactment of the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA)—create inherent conflicts between preservation and access. Victorian storefronts with raised thresholds, narrow entryways in Chinatown alleys, and heavy manual doors in the Financial District represent the “physical barriers” that the OEWD grant aims to dismantle.

The economic implications of these barriers are profound. In a city where foot traffic is a primary revenue driver for neighborhood commercial districts, physical exclusion translates directly to economic loss. The Department of Public Works and the Mayor’s Office on Disability have long recognized that retrofitting this infrastructure is capital-intensive. The Accessible Barrier Removal Grant emerged not merely as a social welfare program, but as an economic stimulus measure designed to lower the entry cost for compliance, thereby protecting small legacy businesses from the existential threat of predatory litigation.1

1.2 The Digital Shift and the “Invisible” Barrier

While the physical challenges are visible, a parallel crisis has emerged in the digital sphere. The COVID-19 pandemic accelerated the shift to e-commerce, forcing thousands of San Francisco restaurants, retailers, and service providers to rely on digital channels for survival. This migration exposed a critical vulnerability: the vast majority of small business websites were not designed with accessibility in mind.

Digital barriers—such as images lacking alternative text (alt-text), forms that cannot be navigated via keyboard, and low-contrast color schemes—effectively lock out users with visual, motor, or cognitive impairments. In California, the legal consequences of this exclusion are severe. The Unruh Civil Rights Act (California Civil Code § 51) provides for statutory damages of at least $4,000 per violation. Unlike physical barriers, which require a site visit to identify, digital barriers can be identified remotely by automated scanning tools, leading to a surge in high-volume litigation against San Francisco businesses.3

This report posits that the modern definition of “Barrier Removal” must be bifurcated:

- Physical Barrier Removal: Addressed by the OEWD Grant and CASp inspections.

- Digital Barrier Removal: Addressed by a distinct stack of private grants, tax credits, and strategic investments.

Understanding this distinction is the single most important factor for a business owner seeking to utilize public funds effectively.

2: The Accessible Barrier Removal Grant – Mechanics and Implementation

2.1 Program Architecture and Funding Source

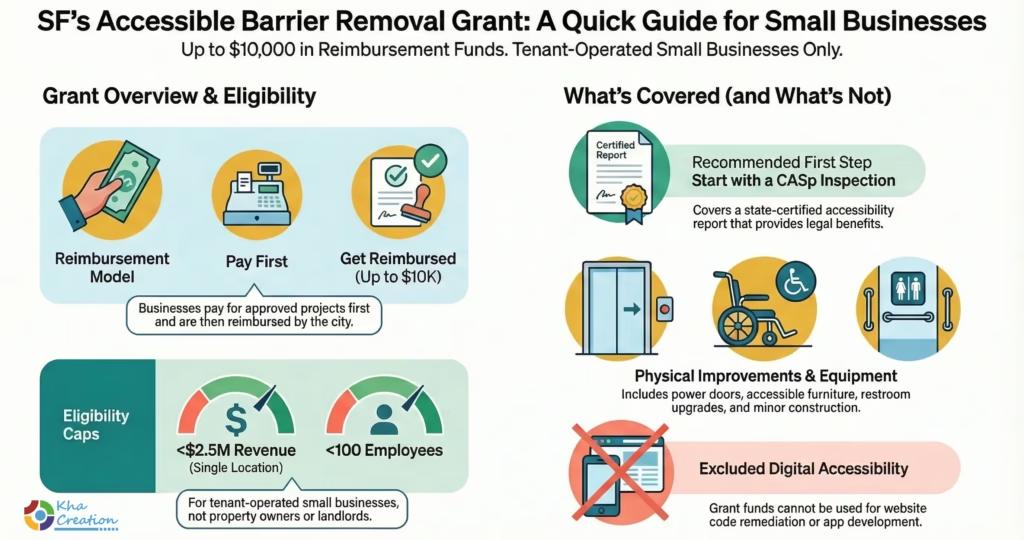

The Accessible Barrier Removal Grant is a reimbursement-based financial aid program administered by the San Francisco Office of Economic and Workforce Development (OEWD) in partnership with the Office of Small Business. The program is capitalized through general city funds allocated for economic recovery and neighborhood improvement.1

It is critical to understand the “reimbursement” nature of the grant. Unlike an upfront cash infusion, this model requires the business owner to possess sufficient working capital to pay for the improvements or inspections first. The City then processes the claim and issues a check. This structure is designed to ensure fiscal integrity and verify that funds are strictly applied to eligible accessibility projects.

Table 1: Core Parameters of the Accessible Barrier Removal Grant

| Parameter | Specification | Strategic Implication |

| Maximum Award | Up to $10,000 | Sufficient for inspections and minor retrofits (e.g., door openers), but insufficient for major structural changes (e.g., elevators). |

| Disbursement Model | Reimbursement | Requires interim cash flow or bridge financing. |

| Administering Body | OEWD / Office of Small Business | Applications are processed through the official SF.gov portal. |

| Frequency | Rolling / Funding Dependent | Speed is essential; funds are finite and often depleted quickly. |

| Primary Scope | Physical Access & CASp | NOT typically applicable to website code remediation. |

2.2 Detailed Eligibility Criteria

The City has established strict eligibility boundaries to target the funds toward the businesses most vulnerable to displacement and litigation. These criteria filter out large corporations and property holding companies, focusing instead on the operator—the tenant running the coffee shop, the bookstore, or the salon.

2.2.1 Business Profile and Ownership

To qualify, an entity must be a registered business in San Francisco with a valid Business Account Number (BAN). Crucially, the applicant must be the owner/operator of the business location. While property owners (landlords) bear ultimate responsibility for common areas under the ADA, this grant is designed to assist the commercial tenant, who is often assigned responsibility for interior compliance through triple-net leases.6

Property owners are generally ineligible unless they also own and operate the business housed within the property. This distinction prevents the grant from acting as a subsidy for real estate portfolio holders, directing it instead to active economic contributors.

2.2.2 Financial and Operational Thresholds

The grant utilizes revenue and employment caps to define “small business”:

- Revenue: The business must have less than $2.5 million in gross annual revenue for a single location. For businesses with multiple locations, the aggregate gross revenue must be less than $8 million.6 This threshold is carefully calibrated to include successful local independents while excluding regional chains.

- Employees: The business must employ an average of 100 or fewer employees. This is a relatively high cap compared to federal micro-business definitions (often 20 or fewer), reflecting the labor-intensive nature of San Francisco’s hospitality and service sectors.6

- Tenure: In certain iterations of OEWD grants (like the Storefront Grant), there are requirements for lease longevity (e.g., 24 months remaining) or historical operation (20+ years). While the Barrier Removal Grant is more flexible, long-term tenure signals stability to grant reviewers.7

2.3 Allowable Expenditures: The Physical Focus

The grant’s eligible expenses are rigorously defined to prioritize physical access. This is the area of greatest confusion for applicants seeking “digital” funding.

2.3.1 The Certified Access Specialist (CASp) Inspection

The most strategic use of the grant is to fund a CASp inspection. A CASp is a professional certified by the State of California to evaluate properties for compliance with construction-related accessibility standards.

- Cost Coverage: The grant covers the full cost of the inspection and the resulting report.5

- Legal Benefit: Possessing a CASp report grants the business “Qualified Defendant” status in state court. This status can:

- Extend the timeline to respond to a lawsuit.

- Mandate an early evaluation conference to settle claims efficiently.

- Potentially reduce statutory damages if corrections are made within specific windows (e.g., 60 days).

- Strategy: Experts recommend using the grant for this inspection before any construction begins. The CASp report serves as the master plan for remediation.

2.3.2 Furniture, Fixtures, and Equipment (FF&E)

The grant covers the purchase and installation of tangible items that improve accessibility.1 Common approvals include:

- Power Door Operators: Automatic buttons for entry doors. This is a high-impact upgrade that benefits wheelchair users, parents with strollers, and delivery workers.

- Accessible Furniture: Lowered service counters, ADA-compliant dining tables, and accessible shelving units.

- Restroom Upgrades: Grab bars, angled mirrors, and under-sink pipe insulation (to protect legs from burns).

2.3.3 Construction and Labor

Small-scale construction projects are eligible, such as leveling an entryway threshold, widening a doorway to the standard 32-inch clearance, or restriping a parking lot to include a van-accessible space. However, applicants must ensure that all construction work is performed by licensed contractors and that appropriate permits are pulled from the Department of Building Inspection (DBI).2

2.4 The “Digital” Exclusion and Ambiguity

It is vital to address the user’s specific query regarding a “Digital Accessible Barrier Removal Grant.” Based on a comprehensive review of the OEWD guidelines and grant documentation 5, there is currently no explicit component of the Accessible Barrier Removal Grant designated for website code remediation or app development.

The grant mentions “Professional design services” 7, which some applicants interpret as potential funding for web design. However, in the context of the OEWD’s definitions, “design services” refers to architectural and engineering plans required for physical construction permits. Attempting to claim website development costs under this line item carries a high risk of rejection during the reimbursement phase.

Consequently, while the grant is a powerful tool for the physical realm, relying on it for digital compliance is a strategic error. 4 of this report details the alternative funding sources that must be activated to address the digital gap.

3: The Digital Accessibility Crisis in San Francisco

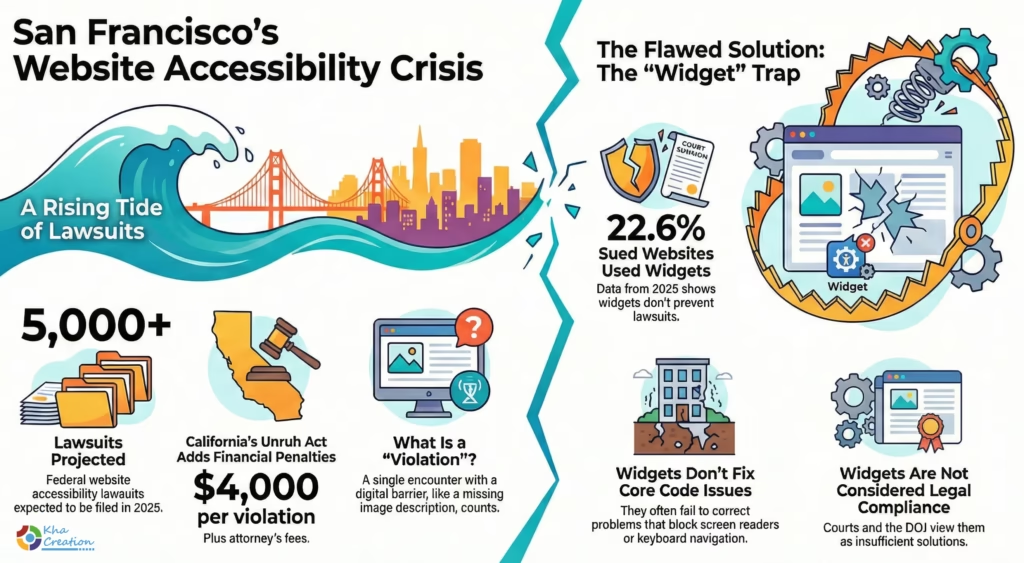

3.1 The Legal Pivot to Title III

While physical barriers remain an issue, the frontier of ADA litigation has shifted to the internet. Since 2018, the number of federal lawsuits alleging website inaccessibility has exploded. In 2025, over 5,000 such lawsuits are projected to be filed federally, with California leading the nation in state-level filings.3

The legal argument rests on the interpretation of Title III of the ADA. Courts in the Ninth Circuit (which includes California) have generally held that a website constitutes a “place of public accommodation” when there is a “nexus” between the website and a physical location. For example, if a San Francisco bakery’s website allows customers to order cakes for pickup, the website is heavily intertwined with the physical service. If a blind customer cannot use the website’s ordering form because it is incompatible with their screen reader (software that reads text aloud), they have been denied equal access to the bakery’s services.

3.2 The Unruh Act Multiplier

San Francisco businesses face a double-edged sword: the federal ADA and the state Unruh Civil Rights Act.

- ADA (Federal): Provides for injunctive relief (fixing the problem) and attorney’s fees, but no monetary damages to the plaintiff.

- Unruh Act (California): Adopts the ADA standards but adds teeth. Any violation of the ADA is a violation of the Unruh Act. Crucially, the Unruh Act allows for statutory damages of $4,000 per violation.

This statutory provision has created a cottage industry of “high-frequency litigants.” A plaintiff need not prove actual physical harm; the mere encounter with a digital barrier (e.g., missing alt-text on a menu image) constitutes a violation. If a plaintiff visits a website three times and encounters barriers, the statutory damages can quickly escalate to $12,000, exclusive of the plaintiff’s attorney fees (which often range from $10,000 to $20,000) and the cost of defense.11

3.3 The “Widget” Trap

In response to this threat, many small businesses have turned to low-cost “accessibility widgets” or overlays—automated tools that add a toolbar to the website allowing users to adjust contrast or font size.

- The Reality: Data from 2025 indicates that 22.6% of websites sued for accessibility had widgets installed.10

- The Problem: Widgets often fail to correct the underlying code deficiencies that block screen readers. For instance, a widget cannot automatically generate meaningful alt-text for a complex image or fix a keyboard trap where a user gets stuck in a form.

- Legal Standing: Courts and the Department of Justice have increasingly indicated that widgets do not equal compliance. They are viewed by the disability community as separate-but-equal half-measures that often interfere with the user’s own assistive technology.3

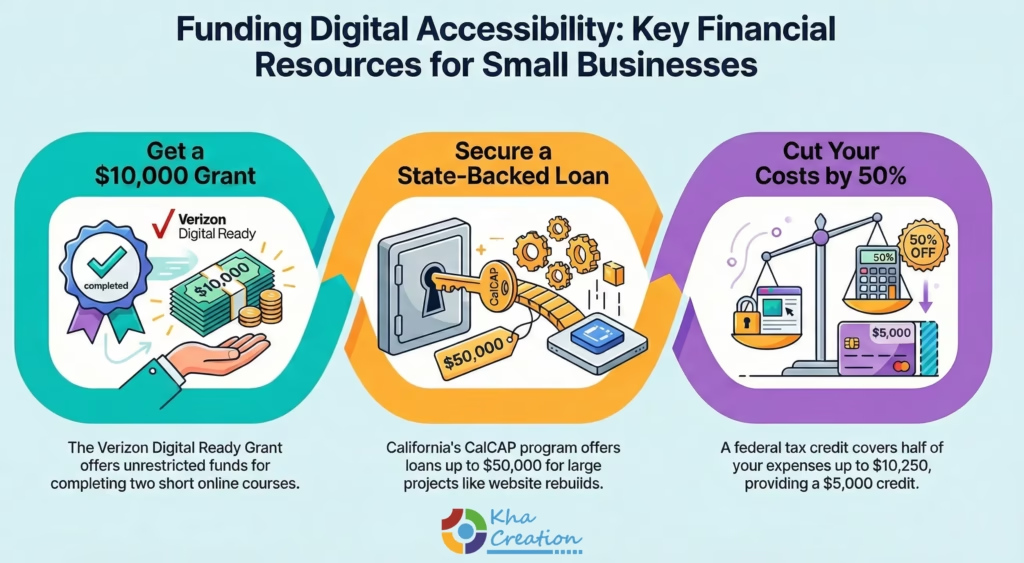

4: Financing the Digital Fix – Alternatives to the SF Grant

Since the OEWD grant is restricted to physical barriers, San Francisco businesses must assemble a “capital stack” from other sources to fund the necessary digital remediation (which typically costs between $3,000 and $15,000 for a thorough audit and fix).

4.1 Verizon Small Business Digital Ready Grant

The most direct source of “free money” for digital work is the Verizon Small Business Digital Ready program.

- Mechanism: This is a corporate philanthropy initiative partnered with agencies like National ACE. It is not a reimbursement; it is a direct grant.

- Value: $10,000.

- Eligibility: Open to small businesses that register on the portal and complete two short online courses (e.g., on digital marketing or finance).

- Relevance: The funds are unrestricted regarding the specific vendor, making them ideal for hiring a specialized digital accessibility consultant to perform a WCAG 2.1 AA audit and remediation.13

4.2 CalCAP/ADA Financing Program (State of California)

For businesses requiring more significant capital (e.g., a complete website rebuild or mobile app development from scratch), the California Capital Access Program (CalCAP) offers a robust financing option.

- Structure: This is a loan, not a grant. However, the State Treasurer’s Office deposits a cash reserve into a “loss reserve account” for the lender for every loan enrolled. This incentivizes banks to lend to small businesses that might have slightly lower credit scores or collateral.

- Allowable Uses: The program explicitly covers “physically altering or retrofitting existing small business facilities.” As the legal definition of “facility” expands to include digital infrastructure under the nexus theory, many participating lenders are accepting loan applications for comprehensive ADA overhauls that include digital compliance costs, provided they are part of a broader compliance strategy.14

- Terms: Loans up to $50,000.

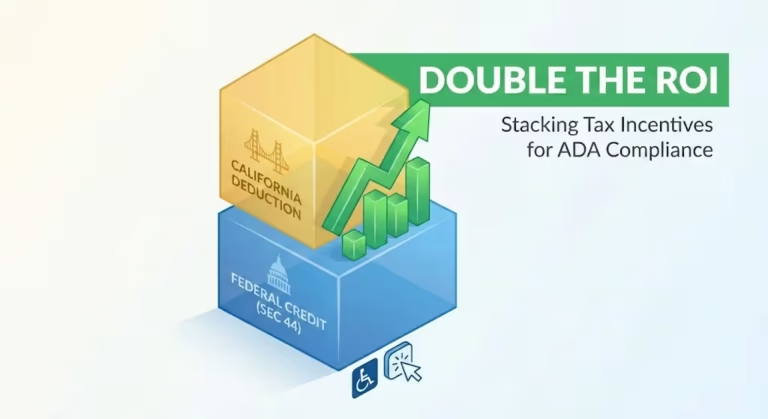

4.3 The Federal Disabled Access Credit (IRS Form 8826)

This is the most underutilized financial tool. It is a federal tax credit, meaning it reduces the tax bill dollar-for-dollar.

- Eligibility: Businesses with gross receipts under $1 million or fewer than 30 full-time employees.

- Calculation: The credit covers 50% of eligible access expenditures between $250 and $10,250.

- Maximum Value: $5,000 per year.

- Application: Digital accessibility audits and remediation are considered eligible “communication aids” under the IRS code. By spending $10,000 on digital compliance, a business can receive a $5,000 tax credit, effectively halving the cost.16

5: The Strategic Nexus – Accessibility, SEO, and GEO

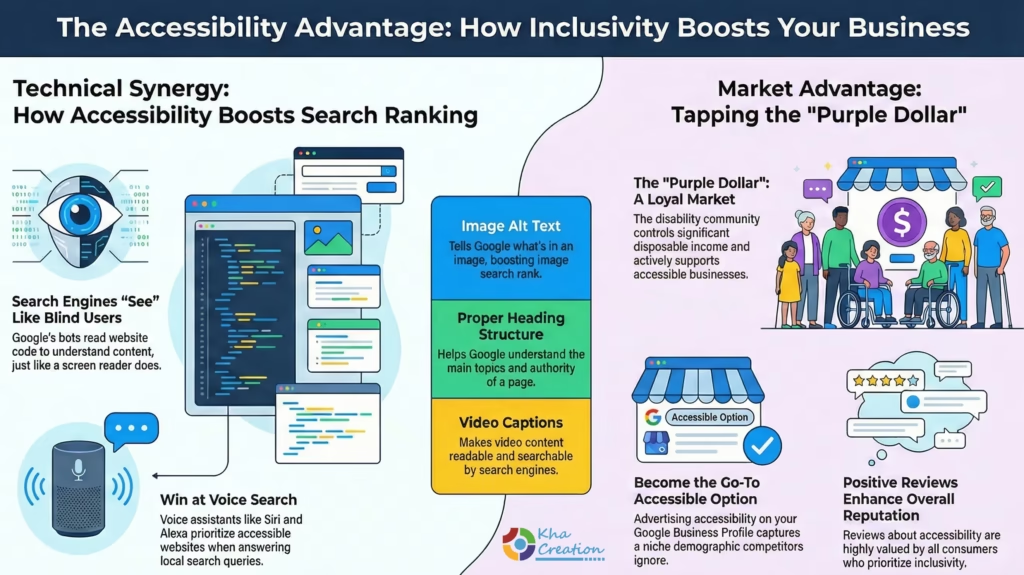

For the modern San Francisco business, accessibility is not merely a compliance burden; it is a potent marketing accelerant. The technical requirements for accessibility (WCAG 2.1 AA) are nearly identical to the technical best practices for Search Engine Optimization (SEO) and the emerging field of Generative Optimization (GEO).

5.1 SEO and the Machine Reader

Search engines like Google are, in essence, blind users. They use “spiders” or “bots” to crawl websites, reading the code to understand the content.

- Alt Text: When a business adds descriptive alt text to an image of “Clam Chowder at Fisherman’s Wharf” for a blind user, they are simultaneously telling Google exactly what the image contains. This boosts the image’s ranking in Google Image Search.

- Heading Structure: Screen readers navigate by jumping from Heading 1 (H1) to Heading 2 (H2). Google uses this same hierarchy to determine the main topics of a page. A properly nested heading structure signals a high-quality, authoritative page to search algorithms.

- Video Captions: Providing transcripts and captions for video content makes that content accessible to the deaf. It also makes the content readable by search engines, allowing the video to show up in text-based search queries.18

5.2 GEO and the Local Search Ecosystem

Geographic Optimization (GEO) focuses on ranking for location-based queries (e.g., “Best Italian food near Union Square”).

- Voice Search: A significant portion of local searches are performed via voice assistants (Siri, Alexa, Google Assistant). These AI systems prioritize results that have structured, accessible data. An accessible website is more easily parsed by these AIs, increasing the likelihood of being the spoken answer to a voice query.

- Reputation Signals: Google’s “Helpful Content” updates increasingly penalize sites with poor user experience (UX). High bounce rates (users leaving immediately) signal poor quality. Inaccessible sites have high bounce rates for disabled users. By fixing accessibility, businesses improve overall UX metrics, which signals to Google that the site is relevant to the local geography.

5.3 The “Purple Dollar”

The disability community controls significant disposable income, often referred to as the “Purple Dollar.” In a competitive market like San Francisco, being known as the “accessible option” creates brand loyalty.

- Market Differentiator: A restaurant that advertises “Screen-Reader Friendly Menus” or “Wheelchair Accessible Outdoor Seating” on their Google Business Profile captures a niche but loyal demographic that competitors ignore.

- Social Proof: Positive reviews from the disability community regarding accessibility are heavily weighted by consumers who value inclusivity, enhancing the business’s reputation across the board.

6: A Step-by-Step Compliance Roadmap for SF Businesses

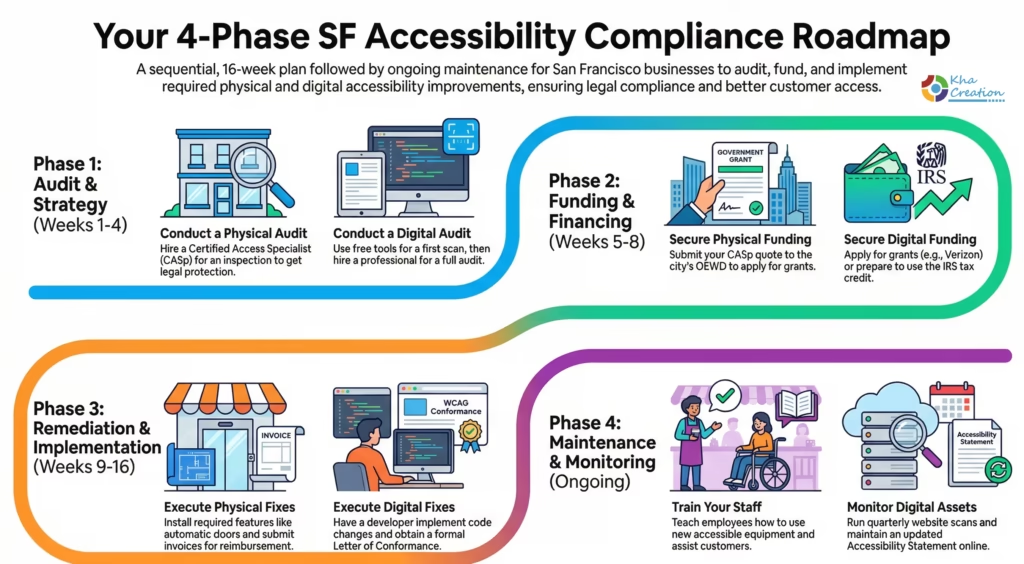

To synthesize the funding and technical strategies, the following roadmap offers a sequential plan for San Francisco business owners.

Phase 1: The Audit & Strategy (Weeks 1-4)

- Register: Ensure the business has a valid SF Business Registration Certificate and BAN.

- Physical Audit: Apply for the SF Barrier Removal Grant to fund a CASp inspection. Do not skip this step. The CASp report is the foundational document for legal protection.

- Digital Audit: Use a free tool (like WAVE) for a preliminary scan, then seek a quote from a professional accessibility consultant for a full manual audit. Do not rely on widget salesmen.

Phase 2: Funding & Financing (Weeks 5-8)

- Submit Grant Application: Submit the CASp quote to OEWD.

- Secure Digital Funding: Apply for the Verizon Digital Ready Grant or prepare to utilize the IRS Form 8826 Tax Credit at year-end.

- Review Leases: Check the commercial lease. If the lease puts the burden of ADA compliance on the tenant (standard in triple-net leases), document this for the grant application to prove “Owner/Operator” liability.

Phase 3: Remediation & Implementation (Weeks 9-16)

- Execute Physical Fixes: Install the automatic door openers, adjust counter heights, and stripe the parking lot. Submit paid invoices to OEWD for reimbursement.

- Execute Digital Fixes: Have the web developer implement the code changes (Alt text, ARIA labels, contrast adjustments).

- Critical Step: Obtain a VPAT (Voluntary Product Accessibility Template) or a Letter of Conformance from the developer upon completion.

Phase 4: Maintenance & Monitoring (Ongoing)

- Staff Training: Train employees on how to use the new physical equipment (e.g., not blocking the accessible door button with a trash can) and how to assist customers with digital issues (e.g., taking phone orders if the website glitches).

- Quarterly Scans: Run automated scans on the website every quarter to catch new errors introduced by content updates.

- Statement: Maintain an up-to-date Accessibility Statement on the website footer with a 24/7 contact method (phone or email) for reporting barriers.

7: Future Outlook and Policy Recommendations

The trajectory of accessibility in San Francisco points toward a convergence of the physical and digital. As initiatives like the Chinatown Wi-Fi Project 20 expand digital infrastructure, the City’s definition of “public accommodation” will likely evolve. It is anticipated that by 2027, municipal grants may explicitly include digital remediation as an allowable expense, recognizing that a business without an accessible website is effectively closed to a large segment of the population.

For the interim, the “smart” business owner views accessibility not as a tax, but as an investment in infrastructure. Just as seismic retrofitting protects the building from earthquakes, accessibility retrofitting protects the business from the shockwaves of litigation and the slow erosion of market share. By leveraging the SF Barrier Removal Grant for the physical and private capital/tax credits for the digital, San Francisco businesses can build a resilient, inclusive foundation for the future.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ)

Q1: I searched for “SF Digital Accessible Barrier Removal Grant” but can’t find an application. Does it exist?

A: Technically, no. There is no specific city grant with that exact title. The City offers the Accessible Barrier Removal Grant, which is primarily for physical barriers (CASp inspections, construction, equipment). For digital funding, you should look at the Verizon Digital Ready Grant or use the Federal Disabled Access Tax Credit to offset costs. Do not assume the City grant covers website code unless explicitly confirmed by a case manager.1

Q2: Can the Barrier Removal Grant pay for a new point-of-sale (POS) system?

A: Potentially, yes. If the new POS system is specifically purchased to be accessible (e.g., it has a tactile keypad for the blind or is mounted on an adjustable arm for wheelchair users), it may qualify as “Equipment.” You must justify the accessibility function in your application.7

Q3: What is the difference between a CASp report and a regular building inspection?

A: A regular building inspection checks for code compliance at the time of construction. A CASp inspection specifically checks for compliance with state and federal accessibility laws (CRASCA). Only a CASp report gives you “Qualified Defendant” status in court, which is a powerful legal shield against high-frequency lawsuits.5

Q4: My website has an accessibility icon (a widget). Am I safe from lawsuits?

A: Likely not. Data shows that over 20% of lawsuits target sites with widgets. Widgets often fail to fix the deep code issues that block screen readers. Relying on a widget is considered a “band-aid” and may not stand up in court as effective communication. True compliance requires remediation of the website’s source code.3

Q5: How long does it take to get reimbursed by the City?

A: The application review typically takes about 15 days. Once approved and the work is completed, reimbursement processing can take several weeks (30-60 days) depending on the volume of claims. You must have the cash flow to pay the contractor upfront.21

Q6: Can I use the grant to fix my bathroom if my business is on the second floor without an elevator?

A: This is complex. If the primary barrier (the lack of an elevator) prevents access to the second floor, fixing the bathroom might be seen as a secondary priority. However, the grant can pay for a CASp inspector to evaluate your site and determine if installing an elevator is “readily achievable.” If it is not, the report helps legally justify why you haven’t installed one, and the grant might then fund alternative service methods (e.g., a buzzer and delivery system).2

Q7: Does accessibility really help my SEO?

A: Yes. Accessibility features like alt-text, transcripts, and clear headings help Google’s bots understand your content better. This can improve your rankings in general search, image search, and voice search results. It is one of the few investments that helps with both legal compliance and marketing.18

Q8: What if I have multiple locations?

A: You can apply for the grant for each eligible location, provided each location generates less than $2.5 million in revenue and the total business revenue is under $8 million. Each location requires a separate application and separate CASp report.6

Key Data Tables

Table 2: Comparative Analysis of Accessibility Funding Sources

| Funding Source | Type | Max Value | Primary Use Case | Digital Eligibility? |

| SF Barrier Removal Grant | Reimbursement Grant | $10,000 | CASp, Ramps, Doors, Restrooms | No (Generally Excluded) |

| Verizon Digital Ready | Direct Grant | $10,000 | Tech upgrades, Marketing, Website | Yes (Highly Recommended) |

| CalCAP/ADA Program | Loan (Loss Reserve) | $50,000 | Major Retrofits, Renovations | Conditional (Lender Dependent) |

| Federal Tax Credit (8826) | Tax Credit | $5,000/yr | Offsetting Audit/Remediation costs | Yes (Explicitly Included) |

| Tax Deduction (IRC 190) | Tax Deduction | $15,000/yr | Removal of Physical Barriers | No (Physical Only) |

Table 3: The Cost of Inaction vs. Compliance (2025 Estimates)

| Scenario | Estimated Cost | Breakdown |

| Proactive Compliance | $3,000 – $8,000 | Audit ($2k) + Fixes ($3k) + Staff Training ($1k) – Tax Credit ($3k) |

| Lawsuit Settlement | $20,000 – $45,000 | Plaintiff Damages ($4k-$12k) + Plaintiff Attorney Fees ($15k) + Defense Fees ($10k) |

| Widget Subscription | $600 – $1,000/yr | Monthly fee ($50-$100) |

| Widget Outcome | High Risk | Does not prevent lawsuit; settlement costs still apply. |

Important Links

- SF Office of Small Business – Find a Grant: https://www.sf.gov/information–find-grant-your-small-business 1

- Apply for Storefront & Barrier Removal Grants: https://www.sf.gov/apply-grant-your-small-business-storefront 7

- CalCAP/ADA Financing Program Summary: https://www.treasurer.ca.gov/cpcfa/calcap/ada/summary.asp 14

- Certified Access Specialist (CASp) Directory: https://www.sf.gov/information–certified-access-specialists 8

- Verizon Small Business Digital Ready Program: https://www.sf.gov/news-small-business-newsletter-for-november-2025 13

- SF Chamber of Commerce Small Business Resources: https://sfchamber.com/resources/small-business-resources/ 18

- ADA Website Litigation Trends 2025: https://darroweverett.com/ada-website-accessibility-litigation-insights-legal-analysis/ 10

- Digital Accessibility Lawsuit Tracker: https://info.usablenet.com/ada-website-compliance-lawsuit-tracker 22

- Guide to the Unruh Civil Rights Act: https://www.deque.com/blog/the-unruh-act-understand-the-lawsuits-and-how-state-and-federal-regulations-could-combine-to-create-blockbuster-settlements/ 23

- San Francisco Digital Equity Initiatives: https://www.sf.gov/san-francisco-digital-equity 24

References/ Works cited

- https://www.sf.gov/information–find-grant-your-small-business#:~:text=Improve%20accessibility%20with%20the%20Accessible,more%20accessible%20to%20the%20public.

- Disabled Access Compliance Checklist – San Francisco – SF.gov

- ADA Web Lawsuit Trends for 2026: What 2025 Filings Reveal – UsableNet Blog

- ADA Lawsuit Trends for 2025 to Date: What Business Owners Need to Know

- Improve the ADA accessibility of your business – SF.gov

- Apply for a grant to make your business accessible | SF.gov

- Apply for a grant for your small business storefront – SF.gov

- Certified Access Specialists – SF.gov

- Find a grant for your small business – SF.gov

- The Rising Tide of ADA Website Accessibility Litigation: 2025 Insights | DarrowEverett LLP

- How Can Small and Solo Firms Comply with ADA Website Requirements Without Breaking the Bank

- ADA Compliance Fines: What They Cost & Who’s at Risk – AudioEye

- Small business newsletter for November 2025 – SF.gov

- CPCFA CalCAP/ADA – State Treasurer’s Office

- CalCAP ADA Retrofits (CalCAP ADA) – State Treasurer’s Office – CA.gov

- Disability Access Requirements and Resources | City of Ukiah

- Disability Access Requirements and Resources | Larkspur, CA – Official Website

- Small Business Resources – San Francisco Chamber of Commerce

- My friend got an ada demand letter and showed me the actual settlement agreement they wanted him to sign, this is insane! – Reddit

- Mayor Lurie, Supervisor Sauter Bring Free Public Wifi To Chinatown | SF.gov

- Free Grants and Programs for Small Business | CO- by US Chamber of Commerce

- ADA Compliance Website Lawsuit Tracker – Web Accessibility Resources | UsableNet, Inc.

- The Unruh Act: Understand the lawsuits and how state and federal regulations could combine to create blockbuster settlements – Deque

- San Francisco Digital Equity – SF.gov