Systemic Failures of Automated Accessibility Widgets and the Risks of Quick-Fix Compliance

1. Introduction: The Commodification of Digital Civil Rights

The digital landscape of the twenty-first century has shifted from a static repository of information to a dynamic infrastructure that underpins nearly every aspect of modern life. Access to this infrastructure is no longer a luxury but a civil right, enshrined in legislation such as the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) in the United States, the European Accessibility Act (EAA), and the Accessibility for Ontarians with Disabilities Act (AODA). As the legal imperative for digital inclusion has intensified, so too has the market for solutions capable of addressing the pervasive inaccessibility of the web. It is within this high-pressure environment—fueled by a surge in litigation and the complexity of technical standards—that a specific class of software products known as “accessibility overlays,” “widgets,” or “toolbars” has risen to prominence.

These products, often marketed with aggressive claims of “instant compliance” and utilizing the buzzwords of Artificial Intelligence (AI) and Machine Learning (ML), promise to resolve the intricate challenges of digital accessibility through the insertion of a single line of JavaScript code.1 Vendors of these tools pitch a seductive narrative to business owners: avoid the high costs of manual remediation and the steep learning curve of inclusive design by renting a subscription-based “shield” that automatically repairs accessibility violations in real-time.3

However, beneath the veneer of marketing efficiency lies a profound technical and ethical controversy that has galvanized the global accessibility community. A comprehensive analysis of technical performance data, legal precedents, security assessments, and, most importantly, the lived experiences of persons with disabilities reveals a starkly different reality. Far from being a panacea, accessibility overlays have been identified by experts and users alike as a significant barrier to digital inclusion, a security liability, and a beacon for litigation rather than a shield against it.5

This report serves as an exhaustive examination of the “Overlays Controversy.” It analyzes the systemic failures of these quick-fix widgets, dismantling the myth that automated front-end scripts can substitute for semantic code remediation. Through a detailed review of the mechanics of the Document Object Model (DOM), the limitations of automated testing, the privacy implications of data fingerprinting, and the recent decisive actions by the Federal Trade Commission (FTC), this document argues that the reliance on overlays represents a fundamental misunderstanding of what digital accessibility entails.

2. The Mechanics of the “Quick Fix”: Definition, Architecture, and Marketing

To fully appreciate the scope of the controversy, it is essential to define the technology in question and contrast its operational mechanisms with the established standards of the World Wide Web Consortium (W3C).

2.1 Defining the Accessibility Overlay

An accessibility overlay is a broad term encompassing third-party technologies designed to modify the visual presentation and functional behavior of a website to improve its accessibility for users with disabilities.1 Technically, these tools function as a snippet of JavaScript code inserted into the website’s header or footer. When a user visits the site, this script executes, loading a user interface element—typically a widget icon depicting a wheelchair or a person—over the existing content.2

These widgets generally offer two distinct modes of operation, which vendors often conflate in their marketing materials:

- User-Facing Customization (The Toolbar): This interface allows users to manually modify the site’s appearance. Common features include adjusting font sizes, forcing high-contrast color modes, pausing animations, and changing cursor sizes.9

- Automated Remediation (The “AI” Backend): This is the more controversial component. It involves a background process that scans the webpage’s code as it loads, attempting to identify missing accessibility attributes (such as alternative text for images or ARIA labels) and dynamically injecting them into the page structure using heuristic algorithms.3

2.2 The Fundamental Architectural Flaw: Front-End vs. Source Code

The defining characteristic of an overlay—and its fatal flaw—is that it operates exclusively at the browser level (the “front end”). It does not modify the website’s actual source code or the database that generates the content.9 The original, inaccessible code remains on the server, unchanged. The overlay attempts to “mask” these errors by applying a temporary layer of JavaScript corrections on top of the rendered page.

This architecture creates a fragile dependency. If the user has JavaScript disabled, if the overlay’s server experiences downtime, or if a browser security setting blocks the script (a common occurrence with ad-blockers and privacy extensions), the “accessible” version of the site vanishes instantly, leaving the user with the original, broken experience.12 True accessibility, by contrast, involves “manual remediation”—the process of altering the underlying HTML and CSS to be semantically correct and robust, ensuring the site is accessible regardless of third-party scripts.9

2.3 The “AI” Marketing Engine and Deceptive Practices

The proliferation of overlays is driven less by technical efficacy and more by the fear of litigation. Vendors such as AccessiBe, AudioEye, and UserWay have historically marketed their products as “set-it-and-forget-it” solutions. Their advertising campaigns frequently target small and medium-sized businesses (SMBs) with the promise that installing their widget will guarantee full compliance with the WCAG 2.1 AA standards and the ADA within 24 to 48 hours.4

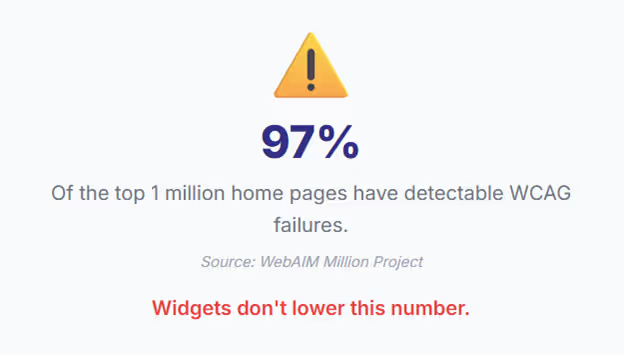

This marketing strategy has drawn intense scrutiny for its deceptiveness. The claim that an automated tool can achieve 100% compliance contradicts the consensus of the entire accessibility engineering field. As noted by the Overlay Fact Sheet, a document signed by nearly 800 accessibility professionals, no automated tool can detect—let alone fix—more than a fraction of WCAG success criteria.3 The disparity between the marketing promise of “full compliance” and the technical reality of “partial, flawed detection” is the nexus of the controversy.

Table 1: The Disparity Between Marketing Claims and Technical Reality

| Feature | Vendor Marketing Claim | Technical Reality |

| Compliance Timeline | “Full compliance in 48 hours” | Impossible; automation misses ~70% of issues.14 |

| Implementation Effort | “One line of code / Zero effort” | Requires constant monitoring; introduces technical debt.9 |

| Legal Protection | “Litigation Support / Guarantee” | No legal shield; correlates with increased lawsuit risk.6 |

| User Preference | “Tailored AI Experience” | Often blocked by users; interferes with native tools.15 |

| Code Impact | “Fixes the code automatically” | Masks the code temporarily; creates “race conditions”.16 |

3. Technical Limitations: Why Automation Fails Semantics

The core failure of accessibility overlays is not merely a lack of sophistication but a fundamental inability of current AI technology to interpret intent. Web accessibility is deeply rooted in the semantic structure of information—the meaning behind the code. While AI can identify patterns, it cannot reliably discern the context necessary to make a website usable for a human being using assistive technology (AT).

3.1 The 30% Ceiling: The Limits of Automated Detection

It is a widely accepted statistic in the digital accessibility industry that automated testing tools—even the most advanced ones used by developers—can detect only 30% to 50% of WCAG violations.14 This limitation exists because the majority of WCAG success criteria are subjective and require human judgment.

For example, an automated script can verify that an image has an alt attribute (a technical requirement). However, it cannot determine if the text within that attribute accurately describes the image (a functional requirement). If an image of a “Buy Now” button has an alt text of “image_123.jpg,” the code is technically valid, but the user experience is broken. Overlays rely on the same automated logic to “fix” pages. If an automated script cannot detect the nuance of an error, it certainly cannot repair it effectively. Consequently, the remaining 50% to 70% of accessibility barriers—often the most critical ones regarding navigation and logic—remain completely unaddressed by the overlay.10

3.2 The “Race Condition” and Render Time Latency

A critical, often overlooked technical failure of overlays involves the timing of code execution. Assistive technologies, particularly screen readers like JAWS (Job Access With Speech) or NVDA (NonVisual Desktop Access), interact with the browser’s accessibility tree as the page renders. Overlays, being third-party JavaScript, typically load and execute after the initial page load to avoid slowing down the site’s visible performance.16

This creates a “race condition.” The screen reader may parse the page and announce the content to the blind user before the overlay has had time to apply its “fixes.” For instance, a user might hear “Unlabeled Button” immediately upon landing on the page. milliseconds later, the overlay might inject a label, but the screen reader focus has already moved on. This lag results in a chaotic, inconsistent user experience where the audio stream contradicts the current state of the DOM, or where the screen reader crashes due to the constant, aggressive manipulation of the page structure.16

3.3 The Failure of Contextual AI: Alt Text and Semantics

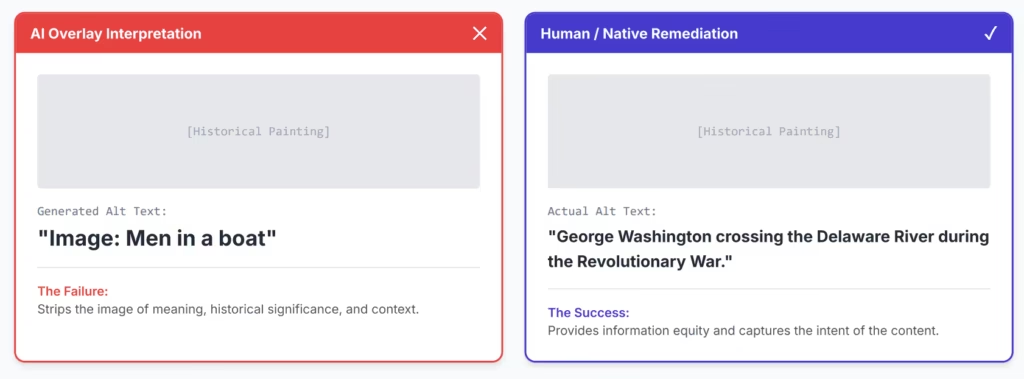

One of the most touted features of AI overlays is image recognition—the ability to automatically generate alternative text for images. In practice, this technology frequently produces results that are useless or actively misleading.

A poignant example cited in technical critiques involves the limitations of computer vision. An overlay might analyze a historical painting of George Washington crossing the Delaware River. Lacking cultural context, the AI might generate alt text such as “Image: Men in a boat”.20 While technically a description, it strips the image of its meaning and historical significance, depriving the blind user of the information equity that WCAG mandates. A human remediator would describe the subject, the action, and the context.

Furthermore, overlays struggle with semantic structure. A visual bold text might imply a heading, but if it lacks an <h1> through <h6> tag, a blind user cannot navigate to it using standard shortcuts. Overlays attempt to heuristically tag these elements but often misidentify navigation bars, footers, or ads as headings. This “repairs” the code by destroying the document outline, making it impossible for a user to understand the hierarchy of the content.12

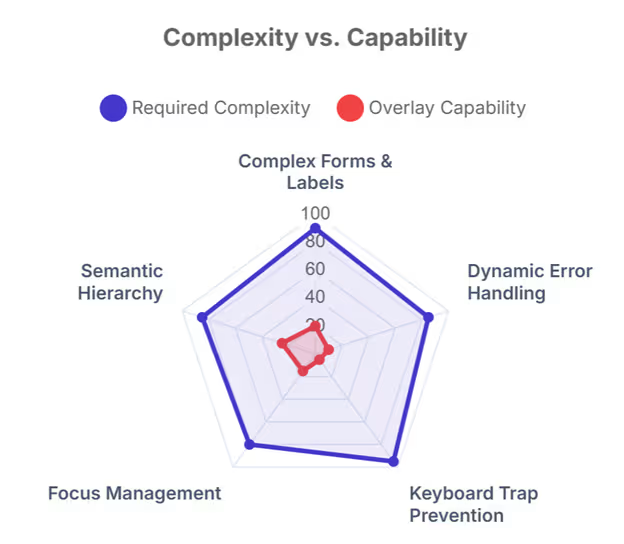

3.4 Logic and State: The Unfixable Barriers

Perhaps the most severe limitation is the inability of overlays to fix interactive logic. Modern web applications rely on complex states—error messages in forms, dynamic content updates, and keyboard focus management.

- Forms: If a form field lacks a programmatic label, a screen reader user does not know what information to enter. AI widgets struggle to associate visual text with input fields correctly, especially in dynamic or complex forms where the label might be distant from the input.13

- Error Handling: When a user makes a mistake in a form, the error message must be programmatically associated with the field (using aria-describedby). Overlays cannot reliably infer which error text belongs to which field, leaving blind users stranded without knowing why their submission failed.17

- Keyboard Traps: A keyboard trap occurs when a user tabs into a widget or modal and cannot tab out. Ironically, the overlay widgets themselves are frequently the source of these traps, locking keyboard-only users into the overlay menu and preventing access to the main site content.22

4. The Human Impact: User Experience, Exclusion, and “Separate but Equal”

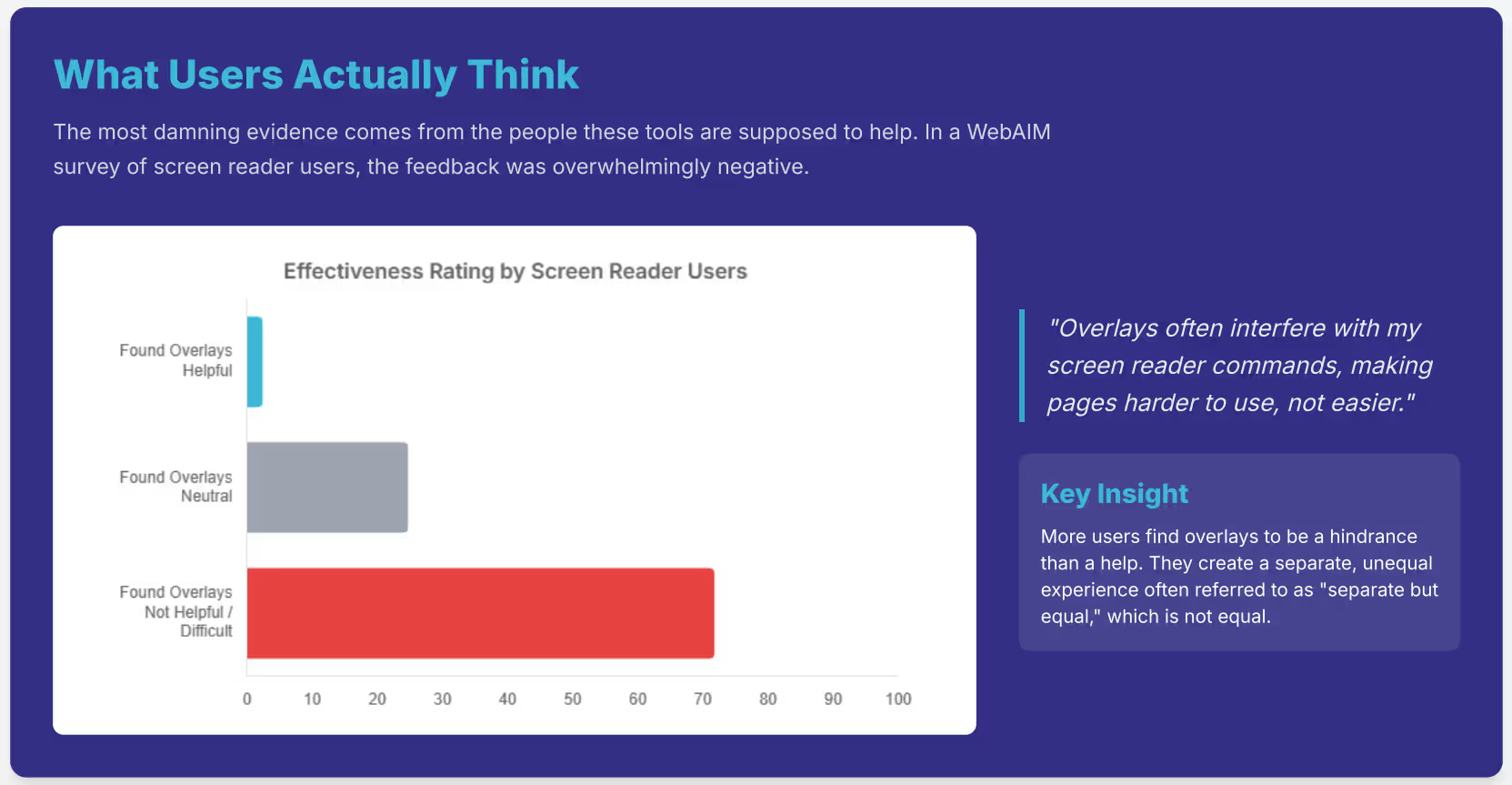

The most damning evidence against overlays comes not from technical audits, but from the people they claim to serve. The disability community has overwhelmingly rejected these tools, viewing them as a form of digital segregation that interferes with their autonomy and established workflows.

4.1 Interference with Assistive Technology

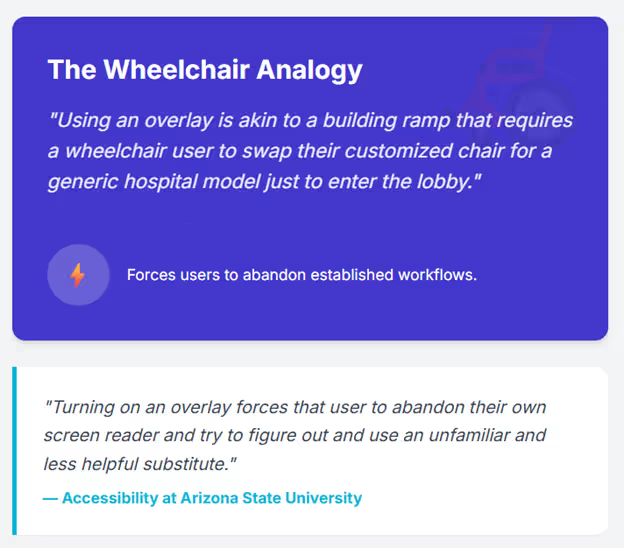

Persons with disabilities are not passive recipients of technology; they are power users of their own specialized tools. A blind user typically has a screen reader (like VoiceOver or JAWS) configured with specific speech rates, verbosity settings, and navigation shortcuts.24 They do not need a website to provide a text-to-speech engine; they already have one that works globally across their operating system.

Overlays frequently override these native settings. For example, an overlay might hijack standard keyboard shortcuts—such as using the arrow keys to scroll or the “H” key to navigate by headings—and repurpose them for the overlay’s internal menu.25 This effectively breaks the user’s primary method of navigation, forcing them to learn a new, often inferior interface for every specific website they visit. This is akin to a building ramp that requires a wheelchair user to swap their customized chair for a generic hospital model just to enter the lobby.7

“Turning on an overlay forces that user to abandon their own screen reader and try to figure out and use an unfamiliar and less helpful substitute.” — Accessibility at Arizona State University.7

4.2 User Testimonials and the “AccessiBye” Phenomenon

The frustration within the community is palpable and documented. A survey by WebAIM (Web Accessibility In Mind) found that 67% of accessibility practitioners rated overlays as “not at all effective” or “not very effective.” Among respondents with disabilities, this dissatisfaction was even higher, with 72% rating them as ineffective and only 2.4% rating them as very effective.5

This profound dissatisfaction has led to a unique form of digital protest: the creation of browser extensions like “AccessiBye,” designed specifically to block accessibility overlays from loading. Users install these blockers so they can attempt to navigate the underlying website without the interference, noise, and instability introduced by the overlay widgets.5

Specific testimonials illustrate the depth of the failure:

- Connor Scott-Gardner, a disability rights activist, recounted a specific irony where an overlay company (AccessiBe) posted a tweet about “blind awareness” that itself contained an image with no alternative text. This highlighted the disconnect between the company’s marketing and its own digital practices.26

- Aaron Page, a blind Director of Accessibility, has described the “hellish experience” of encountering sites where the overlay announces ratings as “unpronounceable” or clutters the audio stream with redundant information, making efficient navigation impossible.5

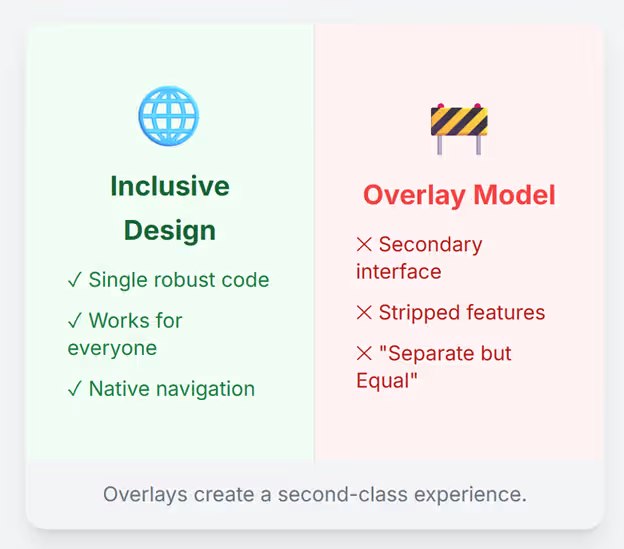

4.3 The “Separate but Equal” Ethical Failure

The philosophy behind overlays promotes a “separate but equal” digital experience. By offering a secondary interface for disabled users rather than fixing the primary interface, overlays suggest that accessibility is an afterthought—a patch to be applied rather than a core quality of the product.

This approach alienates users and erodes brand trust. When a user activates an overlay, they are often presented with a stripped-down, text-only, or simplified version of the site. This contradicts the principles of inclusive design, which advocate for a single, robust experience that is accessible to all users regardless of ability.11 As noted in critiques of the technology, “By using overlays, you are in essence offering people with disabilities a different web experience with reduced functionality, which is in direct contradiction with the goals of digital inclusion”.11

5. The Legal Reality: Litigation, Settlements, and Regulatory Action

The primary selling point of accessibility overlays is legal protection—specifically, insulation from lawsuits filed under Title III of the ADA. Vendors have historically promised that their tools provide a “litigation shield.” However, the legal evidence overwhelmingly suggests that overlays fail to provide this protection and, in many cases, may increase a company’s liability profile.

5.1 Litigation Statistics: The “Beacon” Effect

Data from UsableNet, a firm that tracks digital accessibility litigation, indicates that the presence of an overlay does not deter plaintiffs. In fact, the trend is the opposite. In 2023, over 900 businesses with an accessibility widget on their website were named in federal lawsuits, representing a 62% increase from the previous year.6

Legal experts and defense attorneys suggest that overlays may act as a “beacon” for litigation. They signal to plaintiffs’ law firms that:

- The company is aware it has accessibility issues (evidenced by the purchase of the tool).

- The company has likely not invested in genuine source-code remediation, leaving the underlying infrastructure vulnerable to claims.14 Since overlays cannot fix backend issues like keyboard traps or form labels (as established in Section 3), the site remains non-compliant, and the “beacon” makes it an easy target for testers.

5.2 Case Study: Lighthouse for the Blind v. ADP

One of the most significant legal precedents regarding overlays involves ADP, the global provider of payroll and HR software. The San Francisco Lighthouse for the Blind, along with individual blind employees, sued ADP alleging that its “Workforce Now” platform was inaccessible. At the time of the suit, ADP was utilizing an overlay solution provided by AudioEye.27

The case was settled in 2021, and the terms of the settlement were explicitly damning for the overlay industry. The agreement required ADP to abandon the overlay approach and commit to native accessibility. Crucially, the settlement document stated: “For the purpose of this Agreement, ‘overlay’ solutions such as those currently provided by companies such as AudioEye and AccessiBe will not suffice to achieve Accessibility”.28

This settlement established a powerful legal consensus: overlays are not viewed by advocacy groups or the courts as an acceptable substitute for WCAG compliance or genuine accessibility.

5.3 Case Study: Murphy v. Eyebobs

In the case of Murphy v. Eyebobs, LLC (2021), a blind plaintiff sued an eyewear retailer that used the AccessiBe widget. The plaintiff alleged that despite the presence of the widget, the website remained inaccessible and incompatible with his screen reader.30

The defendant (Eyebobs) argued that the overlay made the site accessible. However, the court did not dismiss the case based on this defense. Instead, the parties entered into a settlement that required Eyebobs to:

- Pay the plaintiff’s legal fees and an incentive award of $1,000.

- Conduct genuine manual remediation of the website to meet WCAG 2.1 AA standards.

- Hire an accessibility coordination team.30 The Eyebobs case serves as a clear warning to businesses: relying on an overlay does not prevent a lawsuit, nor does it serve as a “get out of jail free” card once a suit is filed.

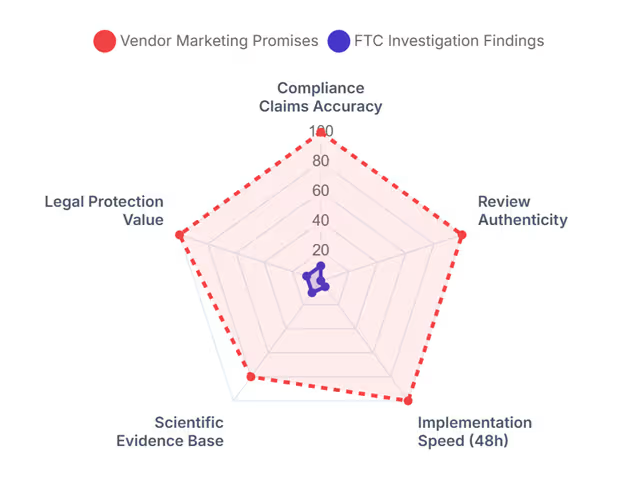

5.4 The FTC vs. AccessiBe: A Regulatory Landmark (2025)

The most devastating blow to the overlay industry occurred in early 2025, when the United States Federal Trade Commission (FTC) took direct enforcement action against AccessiBe, the market leader in overlay technology. The FTC filed a complaint alleging deceptive advertising practices and fined the company $1 million.14

The FTC’s complaint focused on several key areas of deception:

- False Compliance Claims: The FTC alleged that AccessiBe misrepresented its AI’s ability to make websites fully compliant with WCAG standards.

- Unsubstantiated Timeframes: The claim that the tool would ensure compliance within 48 hours was deemed false and misleading.

- Fake Reviews: The company was accused of utilizing paid reviews that were formatted to appear as impartial, independent endorsements.33

The resulting Consent Order prohibits AccessiBe from making unsubstantiated claims about automated compliance and requires them to possess competent and reliable scientific evidence to support any future claims regarding their product’s efficacy.34 This regulatory action effectively neutralizes the core value proposition of the overlay industry—that they offer a guaranteed, automated path to legal compliance.

6. Privacy, Ethics, and Data Fingerprinting

Beyond functionality and legality, the operation of accessibility overlays introduces serious privacy concerns. To function as advertised—by automatically turning on specific adjustments for screen reader users—some overlays must detect the presence of assistive technology on the user’s device. This necessity leads to the non-consensual collection of sensitive health data.

6.1 The Mechanics of Detection and Fingerprinting

Overlays often scan the user’s browser environment for “signatures” or behavioral patterns associated with screen readers (e.g., the speed of navigation, the use of specific keyboard shortcuts). When a match is found, the overlay activates specific profiles, such as a “Blind Profile”.5

This process effectively “fingerprints” the user. By identifying that a visitor is using a screen reader, the overlay vendor identifies that the user has a disability. In the context of data privacy, this is not merely technical data; it is health data.

6.2 Regulatory Risks: GDPR and CCPA

The collection of this data poses significant risks under major privacy regulations:

- GDPR (Europe): Under the General Data Protection Regulation, data concerning health is classified as “Special Category Data” (Article 9). Processing such data is prohibited unless the user gives explicit, informed consent. Overlays typically collect this data automatically upon page load, without asking the user, constituting a potential violation of EU law.5

- CCPA (California): The California Consumer Privacy Act also classifies disability status as sensitive personal information. The unauthorized tracking of this status, especially if used for profiling, creates legal exposure for the website owner.9

6.3 The Threat of Digital Redlining

There is a profound ethical concern regarding how this data might be used. Users and privacy advocates fear that if overlay vendors build databases of users known to have disabilities, this data could be sold or used for discriminatory purposes—a practice known as “digital redlining.” For example, a user identified as blind might be targeted with predatory advertising or excluded from certain financial offers. The Overlay Fact Sheet highlights that this exposure of disability status is a violation of the user’s right to privacy and anonymity on the web.36

7. Security Vulnerabilities: The Hidden Risks of Third-Party Script Injection

While the conversation often focuses on accessibility, the security implications of overlays are equally critical for enterprise risk management. Installing an overlay requires adding a third-party script to the website’s codebase, which introduces a new attack vector.

7.1 Cross-Site Scripting (XSS) and Supply Chain Attacks

An overlay functions by injecting code into the DOM. This mechanism is inherently similar to how malicious actors execute Cross-Site Scripting (XSS) attacks. If the overlay vendor’s servers are compromised, or if the script itself contains a vulnerability, attackers can inject malicious code into every website using that overlay.37

This is a classic “supply chain attack” scenario. Because the overlay script typically requires high-level permissions to manipulate the page content, a compromised script could potentially:

- Steal user session cookies.

- Redirect users to phishing sites.

- Keylog sensitive data entered into forms (such as credit card numbers or passwords).39

7.2 Lack of Control and Stability

Website owners have no control over the code being served by the overlay vendor. Updates are pushed automatically. If a vendor pushes a buggy update, it can break the website’s functionality immediately. Furthermore, because overlays are hosted on third-party servers, they can negatively impact site load times and performance, which are critical factors for both user experience and Search Engine Optimization (SEO).9

8. The Economic Fallacy of “Cheap” Compliance

The primary driver for overlay adoption is the perceived cost differential. Manual remediation is viewed as expensive, labor-intensive, and slow, while overlays are sold as a low-cost subscription (e.g., $49/month). However, this economic calculation is deeply flawed when viewed through a Total Cost of Ownership (TCO) lens.

8.1 Subscription vs. Investment: The “Rent” Problem

An overlay is a perpetual rental. The moment the subscription payment stops, the overlay is removed, and the accessibility features disappear, leaving the site exactly as broken as it was before. Over a period of three to five years, the cumulative cost of an enterprise-level overlay subscription often rivals or exceeds the cost of a one-time, thorough manual audit and remediation.14

Manual remediation, by contrast, is an investment in the asset. Once the code is fixed, it belongs to the site owner. While maintenance is required, the heavy lifting is a capital improvement, not an operational dependency.

8.2 Technical Debt and the “Rot” of Skills

Relying on an overlay creates a moral hazard for development teams. Developers stop learning accessible coding practices because they believe the “magic line of code” handles it. This leads to the accumulation of massive technical debt. The underlying code becomes increasingly inaccessible over time as new features are added without accessibility considerations. When the overlay inevitably fails—due to litigation, technical conflict, or vendor bankruptcy—the cost to fix the accumulated rot is astronomical.39

8.3 Brand Damage and Reputational Risk

The brand damage associated with using overlays is growing. As the disability community becomes more vocal, using an overlay signals to customers that the business views accessibility as a nuisance to be automated away rather than a core value. The “Overlay Fact Sheet” actively advises against using these products, marking them as a reputational liability. Companies like ADP and Eyebobs suffered public relations hits alongside their legal settlements, cementing the association between overlays and corporate negligence.41

9. Valid Use Cases and The Path Forward

Is there ever a valid use case for an overlay? Accessibility experts concede very narrow scenarios, but never as a permanent solution.

9.1 The Triage Exception

Overlays may serve as a temporary “band-aid” or triage measure for a legacy site that is scheduled to be decommissioned in the very near future, or during the interim period while a full manual remediation is taking place. This is akin to putting a tarp over a leaking roof while waiting for the roofer; it is not a roof repair.21

However, if an overlay is used in this manner, it must be communicated transparently to users, and it does not absolve the owner of legal liability during that period.

9.2 The Only Viable Solution: Shift Left and Manual Remediation

The consensus among experts, legal bodies, and the disability community is that there is no substitute for manual remediation. The path to true accessibility involves:

- Manual Audits: Engaging qualified professionals (often including native screen reader users) to test the site against WCAG criteria.9

- Source Code Remediation: Fixing the HTML at the source—adding labels, restructuring headings, and ensuring keyboard operability.5

- “Shift Left”: Integrating accessibility into the design and development phase (SDLC) rather than trying to patch it at the end. This prevents issues from reaching production and significantly lowers the cost of compliance.43

10. Conclusion

The “Overlays Controversy” is defined by a tragic gap between promise and reality. The promise is an effortless, AI-driven solution to a complex civil rights issue—a technological silver bullet that saves money and eliminates risk. The reality, however, is a product category that fails to deliver technical compliance, alienates the very users it purports to help, exposes businesses to heightened legal and security risks, and violates fundamental privacy ethics.

The recent FTC ruling against AccessiBe serves as a tombstone for the era of “quick-fix” accessibility. It validates what experts have argued for years: accessibility is not a feature to be injected; it is a fundamental quality of the code itself. It requires intent, context, and human judgment. For organizations committed to genuine inclusion—and genuine legal protection—the only viable path is the hard, necessary work of building websites that work for everyone, from the source code up.

Summary of Key Findings

| Category | The “Overlay” Promise | The Documented Reality |

| Efficacy | “100% WCAG Compliance” | <40% Detection; Cannot fix semantic structure.14 |

| Legal | “Litigation Shield” | Litigation Magnet; 900+ lawsuits in 2023.6 |

| User Experience | “Seamless AI Integration” | Data Fingerprinting; Potential GDPR/CCPA violations 44 |

| Privacy | “Secure and Private” | Data Fingerprinting; Potential GDPR/CCPA violations.44 |

| Security | “Safe Implementation” | Active Interference: Blocks native screen readers.25 |

| Cost | “Low Monthly Fee” | High Long-Term Cost; Technical debt & brand damage.39 |

References / Works cited

- Overlay Fact Sheet – Disability Lead, accessed on December 24, 2025

- A Guide to Accessibility Overlays – Recite Me, accessed on December 24, 2025

- Overlays: Just Another Disability Dongle – Vispero, accessed on December 24, 2025

- Sherwin K. Parikh MD, P.C. v. Accessibe, Inc. – 1:24-cv-04848 – Class Action Lawsuits, accessed on December 24, 2025

- Overlay Fact Sheet, accessed on December 24, 2025

- Key Takeaways from UsableNet’s 2023 Year-End Digital Accessibility Lawsuit Report, accessed on December 24, 2025

- Caution About Accessibility Overlays – ASU IT Accessibility – Arizona State University, accessed on December 24, 2025

- The Skinny on Accessibility Overlays – Colorado Virtual Library, accessed on December 24, 2025

- Accessibility Overlays: What They Are and Why They Fall Short – TPGi — a Vispero company, accessed on December 24, 2025

- Automated Accessibility Tools vs. Overlays: Pros and Cons – AccessAbility Officer, accessed on December 24, 2025

- Accessibility overlays: what you need to know – Siteimprove, accessed on December 24, 2025

- Why Overlay Tools Will Not Make Your Website Accessible, accessed on December 24, 2025

- Why Web Accessibility Overlays Are Not Effective – Sarah Darr, accessed on December 24, 2025

- Accessibility Overlay Widgets Attract Lawsuits, accessed on December 24, 2025

- Do Away with Overlays | Accessible Web, accessed on December 24, 2025

- I use assistive tech – here’s why accessibility overlays don’t work | Zoonou, accessed on December 24, 2025

- Accessibility Overlays in 2025: A Shortcut Companies Should Continue to Avoid, accessed on December 24, 2025

- Looking for ADA experts for manual website remediation & ongoing support : r/accessibility – Reddit, accessed on December 24, 2025

- Not All Accessibility Overlays Are Created Equal – Deque, accessed on December 24, 2025

- Accessibility overlays are evil and they need to die – Silktide, accessed on December 24, 2025

- Accessibility Overlays: What Site Owners Need to Know – ReadSpeaker, accessed on December 24, 2025

- How Keyboard Traps Impact Web Accessibility – The A11Y Collective, accessed on December 24, 2025

- Keyboard trap | Acquia Product Documentation, accessed on December 24, 2025

- My Experience of Navigating the Web as a Blind User – Allyant, accessed on December 24, 2025

- Accessibility Overlays. A Dangerous Shortcut. | theUXProdigy, accessed on December 24, 2025

- People With Disabilities Say This AI Tool Is Making the Web Worse for Them – VICE, accessed on December 24, 2025

- The Legal Risks of Using an Overlay – Tamman Inc, accessed on December 24, 2025

- HR and Payroll Software Leader ADP to Enhance Product Accessibility, accessed on December 24, 2025

- LightHouse for the Blind and Visually Impaired v. ADP TotalSource, accessed on December 24, 2025

- The Infamous Eyebobs Web Accessibility Lawsuit: Here’s What You Want to Know, accessed on December 24, 2025

- 1 IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT WESTERN DISTRICT OF PENNSYLVANIA ANTHONY HAMMOND MURPHY, Plaintiff, v. EYEBOBS, LLC., Defe, accessed on December 24, 2025

- accessiBe Inc. | Federal Trade Commission, accessed on December 24, 2025

- Misleading Artificial Intelligence Claims by Marketer of Website Accessibility Widget Lead to $1 Million FTC Settlement | Consumer Financial Services Law Monitor, accessed on December 24, 2025

- Federal Trade Commission Orders accessiBe to Pay $1M For Misleading Claims Relating to Automated Website Accessibility Remediation Tool | ADA Title III, accessed on December 24, 2025

- 60 Seconds on Sourcing: Web Accessibility Overlays, accessed on December 24, 2025

- accessed on December 24, 2025

- Cross Site Scripting (XSS) – OWASP Foundation, accessed on December 24, 2025

- 3 Types of Cross-Site Scripting (XSS) Attacks | Trend Micro (US), accessed on December 24, 2025

- Why Accessibility Overlays Hurt More Than They Help | Avidano Digital, accessed on December 24, 2025

- Attacks – Security – MDN Web Docs, accessed on December 24, 2025

- Positive Gains in Digital Accessibility Thanks to Legal Settlement, accessed on December 24, 2025

- The Truth About Overlays and Assistive Toolbars – Recite Me, accessed on December 24, 2025

- Why Web Accessibility Overlays Aren’t a Good Solution | Montana Banana, accessed on December 24, 2025

- Why accessibility overlays won’t help you comply with the European Accessibility Act (EAA), accessed on December 24, 2025