Overview: The State of the Siege in San Francisco

The business climate in San Francisco is defined not just by innovation and economic volatility, but by a distinct and pervasive legal hazard: the digital accessibility and privacy lawsuit. For the uninitiated business owner, the first warning shot is often a process server delivering a thick packet of documents alleging violations of the Unruh Civil Rights Act or the California Invasion of Privacy Act (CIPA). These are not typically complaints filed by aggrieved customers who genuinely attempted to purchase goods and failed; rather, they are the industrial output of a legal machine designed to extract statutory damages at scale. This report serves as a definitive operational dossier for San Francisco businesses, detailing the mechanics of this litigation industrial complex, the seismic shift from federal to state courts, and the emerging threats that have transformed a website’s footer code into a liability minefield.

San Francisco occupies a unique position in this landscape. It is the headquarters of the global technology sector, yet its local small businesses—from Mission District taquerias to Marina boutiques—are “Target Zero” for a specific breed of high-frequency litigation. The convergence of California’s generous civil rights statutes, specifically the damages provisions of the Unruh Act, and the aggressive tactics of a handful of plaintiff law firms has created a perfect storm. While the federal Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) provides the baseline for accessibility, it is the state law overlay that monetizes non-compliance. In 2024 and 2025, the threat matrix evolved further as “wiretapping” claims regarding chat widgets and tracking pixels began to eclipse traditional accessibility claims in volume and cost.1

This document analyzes the strategic pivot of plaintiffs following the Ninth Circuit’s ruling in Arroyo v. Rosas, a decision that fundamentally altered the venue of these battles, forcing them out of federal jurisdiction and into the clogged arteries of the California Superior Court system.3 It dissects the “tester” standing arguments used by firms like Potter Handy and Pacific Trial Attorneys, evaluates the efficacy of “overlay” widgets that promise immunity but deliver liability, and provides a granular, technical, and legal roadmap for survival. For the San Francisco business owner, ignorance of these specialized legal mechanisms is no longer a risk—it is a guarantee of future litigation.

1 Anatomy of the Litigation Industrial Complex

1.1 The Economics of Statutory Damages

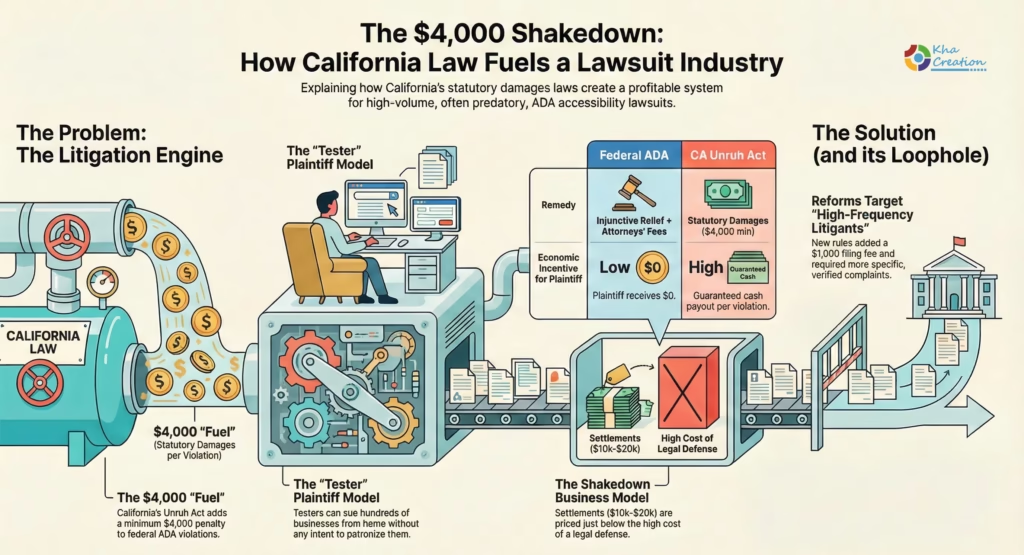

To understand why San Francisco businesses are targeted with such frequency, one must look beyond the stated goals of civil rights legislation and examine the economic incentives codified in California law. The Unruh Civil Rights Act (California Civil Code § 51) was designed to prohibit discrimination in business establishments.5 Crucially, it includes a provision that makes any violation of the federal ADA a per se violation of the Unruh Act. While the ADA provides only for injunctive relief (fixing the barrier) and attorneys’ fees, the Unruh Act allows for the recovery of “statutory damages” of no less than $4,000 per offense.7

This $4,000 minimum is the fuel of the litigation engine. In a traditional tort case, a plaintiff must prove actual damages—money lost, injury sustained, or emotional distress suffered. Proving actual damages requires evidence, medical records, and time. Statutory damages, however, are automatic upon a finding of liability. If a “tester” visits a website and encounters a barrier that violates the ADA, they are theoretically entitled to $4,000 immediately. If they visit the site three times, the claim might rise to $12,000. When multiplied across hundreds of websites visited programmatically or by low-level staffers, the potential revenue stream for a plaintiff’s firm becomes immense, decoupling the litigation from any actual injury or intent to patronize the business.8

The “Litigation Industrial Complex,” a term used by critics and increasingly by defense counsel and prosecutors, refers to the automation of this process. Firms like Potter Handy, LLP (often filing as the Center for Disability Access) have been accused of filing thousands of boilerplate lawsuits. The San Francisco District Attorney, in a high-profile unfair competition lawsuit, alleged that these firms use “cut-and-paste” complaints to circumvent procedural reforms, filing cases with little regard for whether a genuine violation exists.7 The sheer volume is staggering: reports indicate that a small cadre of serial filers accounts for a vast majority of all ADA filings in California, with some individuals filing hundreds of cases annually.8

Table 1: The Multiplier Effect of Statutory Damages

| Legal Framework | Remedy Available | Economic Incentive for Plaintiff | Burden of Proof |

| Federal ADA (Title III) | Injunctive Relief + Attorneys’ Fees | Low: Pays the lawyer, but the plaintiff gets $0. | High: Must prove standing and barrier existence. |

| CA Unruh Act (Civ. Code § 51) | Statutory Damages ($4,000 min) | High: Guaranteed cash payout per violation instance. | Low: Automatic if ADA violation is found. |

| CA CIPA (Penal Code § 631) | Statutory Damages ($2,500 – $5,000) | Very High: Per violation, often per “chat” or page view. | Medium: Must prove “interception” or “device use.” |

1.2 The “Tester” Plaintiff and Standing

The concept of a “tester”—someone who investigates compliance without an intent to purchase—has valid roots in civil rights history, particularly in housing discrimination. However, the digital application of this concept has stretched judicial patience. In the physical world, a plaintiff in a wheelchair must physically travel to a store to encounter a barrier. This imposes a natural geographical limit on how many lawsuits one person can generate. In the digital realm, a plaintiff can “visit” dozens of San Francisco businesses from a living room in San Diego in a single afternoon.

The San Francisco DA’s complaint against Potter Handy highlighted the logical impossibility inherent in these filings. To establish standing in federal court, a plaintiff must allege a “genuine intent to return” to the business. The DA noted that serial filers, some of whom file thousands of cases against businesses hundreds of miles from their homes, cannot plausibly intend to patronize every liquor store, dry cleaner, and boutique they sue.7

Defense attorneys have aggressively attacked this “intent to return” element. If a plaintiff has sued 500 businesses in the Bay Area but lives in Riverside, their claim that they are deterred from visiting a specific marinara sauce shop in North Beach becomes suspect. However, proving this lack of intent requires expensive discovery—depositions, travel records, and credit card statements—which drives up the cost of defense. Consequently, the “shakedown” model works because it prices the settlement (typically $10,000 to $20,000) just below the cost of a vigorous defense.11

1.3 The Procedural Reforms: CCP § 425.55

Recognizing the abuse of the system, the California Legislature enacted Code of Civil Procedure § 425.55 to target “high-frequency litigants.” This statute defines a high-frequency litigant as a plaintiff who has filed 10 or more complaints alleging construction-related accessibility violations within the preceding 12 months.9

For these litigants, the barriers to filing are higher:

- Sur-Filing Fee: An additional $1,000 fee must be paid per case, intended to reduce the profitability of high-volume filing.14

- Verified Complaints: The plaintiff must personally verify the allegations, increasing the risk of perjury for false claims of “intent to return.”

- Specific Pleading: The complaint must detail the specific dates of the visits and the exact barriers encountered, preventing the use of vague boilerplate templates.

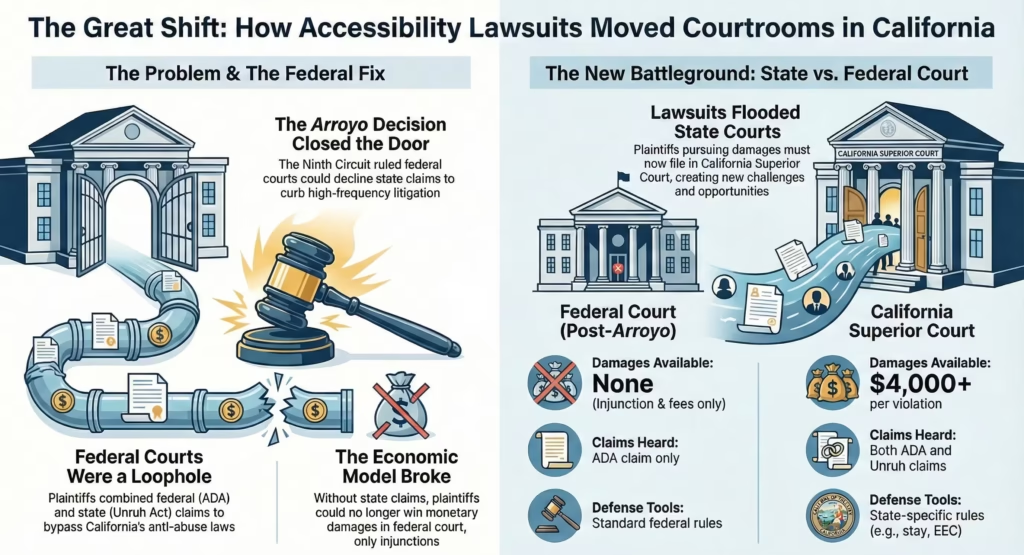

While well-intentioned, these reforms initially drove plaintiffs into federal court, where state procedural rules do not apply. This forum shopping allowed them to bypass the $1,000 fee and the heightened pleading standards while still attaching the state-law Unruh claim. This tactic worked for years until the Ninth Circuit intervened in Arroyo v. Rosas, triggering a massive reverse migration back to state court.3

2 The Great Migration – From Federal to State Court

2.1 Arroyo v. Rosas: The Ninth Circuit Closes the Door

The strategic landscape for Unruh Civil Rights Act defense SF shifted dramatically with the Ninth Circuit’s decision in Arroyo v. Rosas (2021). Prior to Arroyo, federal district courts routinely exercised “supplemental jurisdiction” over state-law Unruh claims that were filed alongside federal ADA claims. This was efficient: one judge heard both the federal and state aspects of the case.

However, the Ninth Circuit recognized that this efficiency was being weaponized to evade California’s legislative reforms (CCP § 425.55). The court ruled that the “exceptional circumstances” of California’s crisis of high-frequency litigation justified federal courts declining jurisdiction over the state claims. The court reasoned that permitting plaintiffs to file in federal court effectively nullified the state’s attempts to curb abuse.3

The impact was immediate. Federal judges began dismissing Unruh Act claims en masse, retaining only the ADA claim. Without the Unruh claim, the potential for monetary damages in federal court evaporated. A plaintiff winning an ADA claim in federal court gets an injunction and attorneys’ fees, but zero dollars in damages. This broke the economic model of the high-frequency litigant in federal venues.4

2.2 The Return to Superior Court

Faced with the loss of their damages claims in federal court, plaintiffs’ firms had no choice but to return to California Superior Court. This shift has flooded local courts, particularly the San Francisco Superior Court, with accessibility lawsuits.

Table 2: Venue Comparison for SF Businesses

| Feature | Federal Court (Post-Arroyo) | California Superior Court |

| Jurisdiction | Retains ADA claim only; dismisses Unruh. | Hears both ADA and Unruh claims. |

| Damages Available | None (Injunctive relief only). | $4,000+ per violation. |

| Pleading Standard | Rule 12(b)(6) (Plausibility). | Demurrer (Fact pleading). |

| Discovery | Structured, mandatory disclosures. | Broad, often burdensome discovery. |

| Cost to Defend | Generally more expensive hourly rates. | Slower proceedings, higher settlement pressure. |

| High-Frequency Rules | Do not apply (generally). | Apply: CCP § 425.55 active. |

For a Potter Handy lawsuit defense strategy, this shift presents both challenges and opportunities. In State Court, the defense can leverage CCP § 425.55 to demand the plaintiff pay the high filing fees and meet strict pleading standards. Defense counsel can also move for a “stay” of proceedings under Civil Code § 55.54, which allows qualifying small businesses to pause the litigation and request an Early Evaluation Conference (EEC) to assess liability and limit damages.15

2.3 The Vo v. Choi Confirmation

The Arroyo doctrine was further cemented by Vo v. Choi (2022), where the Ninth Circuit affirmed that district courts must engage in a case-specific analysis but generally supported the trend of declining supplemental jurisdiction. The court emphasized that comity (respect for state court procedures) outweighs the convenience of trying the claims together.16 This effectively signaled to the plaintiff’s bar that the federal avenue for easy damages was closed, solidifying San Francisco Superior Court as the primary battleground for the foreseeable future.

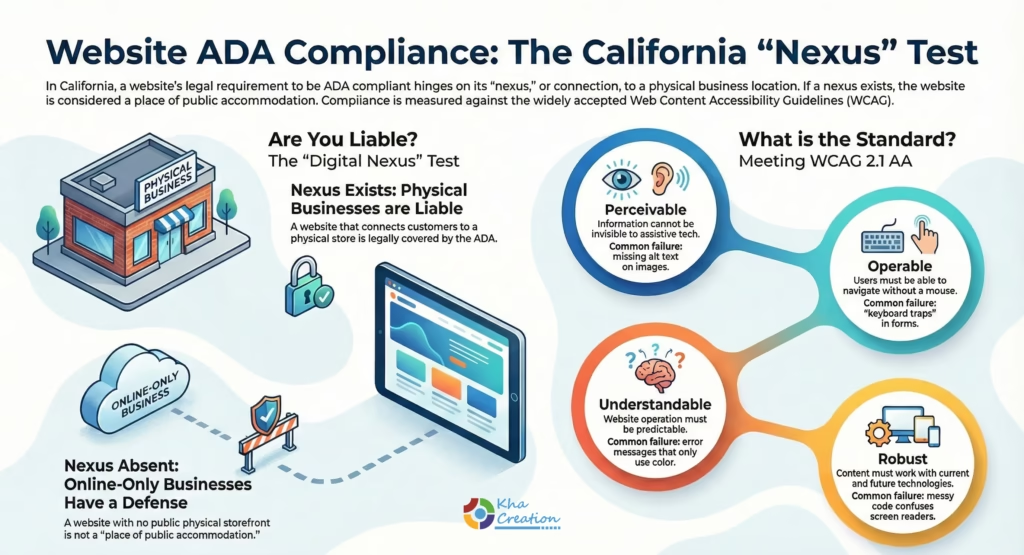

3 The Digital Nexus – When is a Website a “Place”?

3.1 The Robles v. Domino’s Precedent

The question of whether a website constitutes a “place of public accommodation” under the ADA has split federal circuits, but in the Ninth Circuit (covering California), the answer is a definitive “yes”—with conditions. The landmark case Robles v. Domino’s Pizza, LLC established that the ADA applies to websites and apps that connect customers to the goods and services of a physical place.18

In Robles, a blind plaintiff sued Domino’s because he could not order a pizza via their website or app using his screen reader. Domino’s argued that the ADA, written in 1990, did not mention websites and that the lack of official DOJ regulations violated due process. The Ninth Circuit rejected these arguments, holding that the ADA is a broad mandate to provide access and that the lack of specific regulations does not excuse non-compliance. The court emphasized the “nexus” between the digital tool and the physical restaurant: the website was a gateway to the pizza.18

3.2 The “Nexus” Requirement: Thurston vs. Martinez

For website accessibility lawsuit San Francisco defense, the critical legal distinction lies in the “nexus” theory. California courts have bifurcated the liability based on whether the business has a physical footprint.

1. The Nexus Exists (Thurston v. Midvale Corp.):

In Thurston, a blind plaintiff sued a restaurant because the website’s menu and reservation system were inaccessible. The California Court of Appeal held that the website was an extension of the physical restaurant. By denying access to the website, the restaurant was denying full and equal access to its physical services. The court upheld the injunction and the damages, solidifying that brick-and-mortar businesses in SF are fully liable for their digital presence.21

2. The Nexus is Absent (Martinez v. Cot’n Wash):

In a significant victory for e-commerce, the court in Martinez v. Cot’n Wash (2022) held that a purely online business (a detergent retailer with no physical storefront) is not a place of public accommodation under the ADA. The court reasoned that the ADA’s text refers to physical places (hotels, theaters, stores) and that without a physical location to “connect” to, a website does not fall under Title III.24

Implications for SF Businesses:

- Physical Storefronts: If you operate a cafe in the Mission or a bookstore in Haight-Ashbury, your website is covered by Robles and Thurston. You have 100% liability exposure.

- Tech Startups/SaaS: If you are a San Francisco-based software company or e-commerce brand with no physical office open to the public, you have a strong defense under Martinez. However, this defense is specific to California/Ninth Circuit law. If you sell to customers in New York or Florida, you may still be sued in those jurisdictions where the law is different.24

3.3 The Compliance Standard: WCAG 2.1 Level AA

While the law does not explicitly codify the Web Content Accessibility Guidelines (WCAG), courts have universally adopted them as the equitable remedy. Specifically, WCAG 2.1 Level AA is the current gold standard for settlement agreements and consent decrees.26

A “Target Zero” business is one that fails automated scans for basic WCAG principles. These principles are organized under the acronym POUR:

- Perceivable: Information must not be invisible to assistive tech.

- Common Failure: Missing alt tags on images. A screen reader sees <img src=”123.jpg”> and reads “Image one two three,” conveying no meaning.

- Operable: The interface must not require a mouse.

- Common Failure: Keyboard traps. A user tabs into a form or map widget and cannot tab out, effectively freezing the browser.

- Understandable: Operation must be predictable.

- Common Failure: Error messages on forms that use only color (e.g., turning a border red) to indicate an error, which colorblind users cannot perceive.

- Robust: Content must work with current and future user agents.

- Common Failure: Parsing errors in HTML code that confuse screen readers, causing them to skip content or crash.28

4 The New Front – CIPA and the Privacy “Shakedown”

4.1 From Accessibility to “Wiretapping”

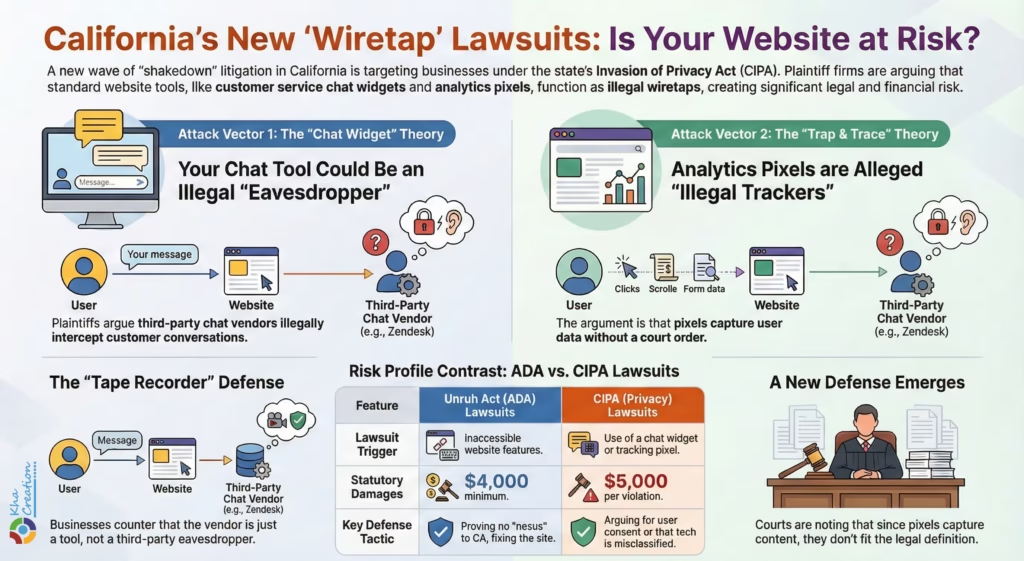

As awareness of ADA compliance has grown, the “Litigation Industrial Complex” has diversified its portfolio. The most explosive growth area in 2024-2025 is litigation under the California Invasion of Privacy Act (CIPA), specifically regarding “Chat Widgets” and “Tracking Pixels.” These cases, often filed by firms like Pacific Trial Attorneys and Tauler Smith, allege that standard website tools constitute illegal wiretapping.1

4.2 The “Chat Widget” Theory (Penal Code § 631)

This theory targets the ubiquitous customer service chat bubbles found on thousands of websites.

- The Statute: CIPA § 631 prohibits “tapping” or “making an unauthorized connection” to a communication, or “aiding and abetting” such an act, without the consent of all parties.31

- The Argument: Plaintiffs argue that because the chat widget is powered by a third party (e.g., Salesforce, Genesys, Zendesk), that third party is an “unannounced eavesdropper” intercepting the conversation between the customer and the business in real-time.

- The “Tape Recorder” Defense: Businesses argue that the third-party vendor is merely a tool, akin to a tape recorder used by a secretary. A tape recorder records the conversation, but it is not a “third party” capable of eavesdropping. Courts have been mixed on this, with some accepting the defense (party exemption) and others allowing the claim to proceed if the vendor allegedly uses the data for its own data mining purposes.33

4.3 The “Trap and Trace” Theory (Penal Code § 638.51)

A newer and more dangerous theory involves CIPA § 638.51, which regulates “Pen Registers” and “Trap and Trace” devices.

- The Statute: It is illegal to install a device that captures “dialing, routing, addressing, or signaling information” without a court order.35

- The Argument: Plaintiffs allege that analytics tools like the TikTok Pixel or Meta Pixel capture the user’s IP address and device routing info. Since the business did not get a court order to install the pixel, they are liable for $5,000 per violation.2

- The Defense (Price v. Headspace): In a critical recent development, the court in Price v. Headspace (2025) and Licea v. American Eagle pushed back. The court noted that “Trap and Trace” devices are legally defined by their inability to capture content. Since tracking pixels capture content (what buttons you click, what you buy), they are definitionally not trap and trace devices. This legal jujitsu has provided a glimmer of hope for defense counsel, but the cost of litigating to that dismissal remains high.38

Table 3: CIPA vs. Unruh Risk Profile

| Feature | Unruh Act (ADA) | CIPA (Privacy) |

| Trigger | Inaccessible website barrier. | Chat widget or Pixel usage. |

| Nexus Required | Yes (in CA state/federal court). | No (Privacy applies to all CA residents). |

| Statutory Damages | $4,000 minimum. | $5,000 per violation (Penal Code 637.2). |

| Primary Plaintiff Firms | Potter Handy, Manning Law. | Pacific Trial Attorneys, Tauler Smith. |

| Key Defense | Martinez (No nexus), Remediation. | Consent (Opt-in), Price (Not a trap/trace). |

5 The Overlay Fallacy – A Trap for the Unwary

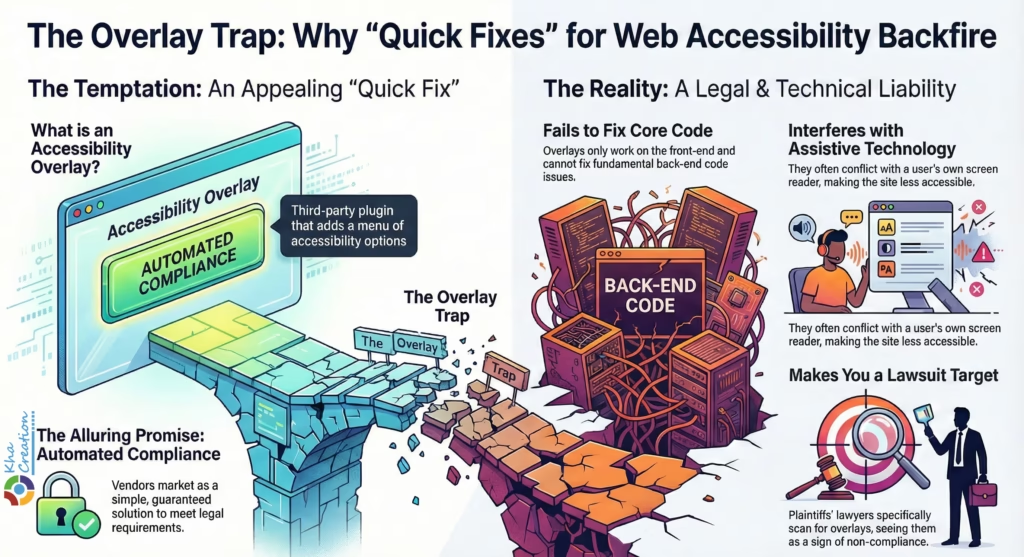

5.1 The “Quick Fix” Temptation

Faced with the complexity of WCAG remediation and the threat of lawsuits, many San Francisco businesses turn to “Accessibility Overlays.” These are third-party plugins that insert a line of JavaScript code, typically displaying a wheelchair icon that opens a menu of accessibility options (contrast, text size, screen reader). Vendors of these tools aggressively market them as an automated solution that guarantees compliance.41

5.2 Why Overlays Fail Legally and Technically

The consensus among accessibility experts and defense attorneys is that overlays are not a solution—they are a liability multiplier.

- Failure to Remediate: Overlays operate on the “front end” (the browser), attempting to modify the page after it loads. They rarely fix fundamental “back end” code issues like missing form labels, keyboard traps, or incorrect heading structures. If the underlying HTML is broken, the overlay cannot fix it sufficiently for a blind user’s native screen reader (e.g., JAWS or NVDA).41

- Interference: Overlays often conflict with the user’s own assistive technology. A blind user typically browses with a sophisticated screen reader. When an overlay forces its own “text-to-speech” feature on the user, it creates a cacophony of competing audio, rendering the site less accessible than before.43

- Target Identification: Plaintiffs’ firms are sophisticated. They know that businesses using overlays are likely relying solely on the overlay and have not performed manual remediation. The presence of the widget code in the website source makes the business easier to find via automated scanning tools. It effectively signals, “We know we have a problem, and we tried a cheap shortcut”.45

- Litigation Reality: Hundreds of lawsuits have been filed against businesses specifically because they used an overlay. In San Francisco, relying on an overlay defense in Superior Court is a perilous strategy, as judges are increasingly educated on the limitations of these tools.41

6 Strategic Defense and Survival

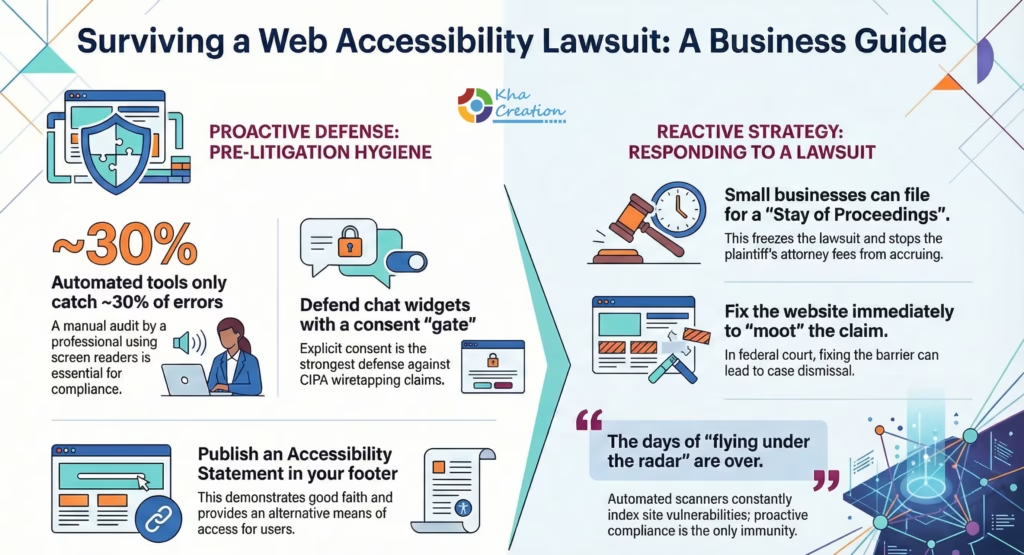

6.1 Pre-Litigation Hygiene

The only true immunity is genuine compliance.

- Manual Audit: Automated tools (like WAVE or Google Lighthouse) catch only ~30% of errors. You must commission a manual audit by an accessibility professional who tests with actual screen readers.41

- Accessibility Statement: Publish a statement in your footer. It should list a 24/7 phone number or email for assistance. While not a complete legal shield, it demonstrates good faith and provides an “alternative means of access” that can be argued in court.46

- Consent Management (CIPA Defense): For chat widgets, implement a “gate.” Before the chat begins, a user must click “I Agree” to a statement that says, “I consent to this chat being recorded and processed by third-party vendors.” This explicit consent is the strongest defense against CIPA wiretapping claims.2

6.2 Responding to the Lawsuit

If you are served, the clock is ticking. You typically have 30 days to respond in state court.

- Do Not Ignore It: A default judgment will award the full damages plus massive attorneys’ fees.

- The “Stay” Tactic: If you are a small business (defined by revenue and employee count), your attorney can file for a “Stay of Proceedings” under Civil Code § 55.54 immediately. This freezes the lawsuit and halts the accrual of the plaintiff’s attorneys’ fees (which are often the largest part of the settlement). It mandates an Early Evaluation Conference (EEC) where the case can often be settled for a lower amount.15

- Challenge Standing: Depose the plaintiff. Ask specific questions about their visit. Did they actually try to buy the product? How many other lawsuits did they file that day? Establish the “tester” nature of their activity to undermine their credibility, even if the “intent to return” standard is looser in state court than federal.7

- Mootness: Fix the website immediately. In federal court, fixing the barrier can “moot” the ADA claim. If the ADA claim is moot, the court loses subject matter jurisdiction over the case, and the Unruh claim may be dismissed (though the plaintiff may re-file in state court).47

6.3 Future Outlook (2025-2026)

The trajectory is clear: the volume of lawsuits is increasing. In 2025, plaintiffs are expected to further refine their CIPA “pixel” arguments, likely targeting specific industries like healthcare (citing medical privacy) and finance. San Francisco businesses must anticipate that the “Litigation Industrial Complex” will continue to automate its processes. The defense must therefore automate its compliance.

The days of “flying under the radar” are over. Automated scanners traverse the web 24/7, indexing vulnerabilities. If your site has a chat widget without consent, or images without alt text, you are already on a list. The only variable is when the process server arrives at your door.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ)

Q1: Why do plaintiffs prefer San Francisco Superior Court over Federal Court now?

A: Since the Ninth Circuit ruling in Arroyo v. Rosas (2021), federal courts often dismiss the state-law Unruh claim, which contains the $4,000 statutory damages provision. By filing in State Court, plaintiffs effectively guarantee they can pursue these damages without the risk of having the claim declined by a federal judge.3

Q2: What qualifies as a “High-Frequency Litigant” in California?

A: Under CCP § 425.55, a high-frequency litigant is a plaintiff who has filed 10 or more complaints alleging construction-related accessibility violations in the last 12 months. This designation triggers higher filing fees ($1,000 extra) and stricter pleading standards for the plaintiff.9

Q3: Does having an “Accessibility Menu” widget protect me from lawsuits?

A: generally No. Legal experts and accessibility advocates warn that these overlays do not fix the underlying code issues required for WCAG compliance. They can create a false sense of security and identify your site as a target for automated lawsuit scanners.41

Q4: My business has no physical store, only a website. Am I liable under the Unruh Act?

A: You have a strong defense. Under Martinez v. Cot’n Wash (2022), California courts have held that a purely digital business is not a “place of public accommodation.” However, this area of law is evolving, and you may still be vulnerable to privacy (CIPA) lawsuits or suits filed in other states.24

Q5: What is the difference between a CIPA “Wiretap” claim and an “Unruh” claim?

A: An Unruh claim is about access (e.g., a blind person cannot use your site). A CIPA claim is about privacy (e.g., your chat widget recorded a conversation without consent). CIPA claims carry higher statutory damages ($5,000 vs $4,000) and do not require the plaintiff to have a disability.1

Q6: What should I do if I receive a demand letter from Pacific Trial Attorneys?

A: Do not engage directly. These firms are highly specialized. Contact a defense attorney who knows the specific “playbook” of Scott Ferrell and Pacific Trial Attorneys. The strategy for CIPA defense (arguing consent or the “tape recorder” exemption) is different from ADA defense.1

Q7: Is the San Francisco District Attorney still suing Potter Handy?

A: The DA’s lawsuit against Potter Handy for unfair competition was largely dismissed based on the “litigation privilege,” which protects lawyers from liability for filing lawsuits. While the DA’s action brought attention to the issue, it did not stop the filings. The burden remains on individual businesses to defend themselves.11

Q8: Can I get insurance for these lawsuits?

A: Maybe. Employment Practices Liability Insurance (EPLI) sometimes covers third-party discrimination claims, including ADA suits. Cyber Liability insurance might cover CIPA/Privacy claims. Check your policies immediately—many general liability policies specifically exclude these types of claims.49

References/ Works cited

- Website Compliance – Karlin Law Firm LLP, accessed on January 12, 2026

- The Rise of “Wiretapping” Legal Claims: Business Websites Are Being Accused of Using “Trap and Trace” Devices – ADA Compliance and Defense Blog, accessed on January 12, 2026

- Legal Update: November 2025 – Converge Accessibility, accessed on January 12, 2026

- Arroyo v. Rosas, No. 19-55974 (9th Cir. 2021) – Justia Law, accessed on January 12, 2026

- California Code, Civil Code – CIV § 51 – Codes – FindLaw, accessed on January 12, 2026

- Civil Code § 51 – Unruh Civil Rights Act – Impact Attorneys, accessed on January 12, 2026

- F I L E D – San Francisco District Attorney’s Office, accessed on January 12, 2026

- Case No. A166490 IN THE COURT OF APPEAL OF THE STATE OF CALIFORNIA FIRST APPELLATE DISTRICT, DIVISION THREE – U.S. Chamber of Commerce, accessed on January 12, 2026

- California Code, Code of Civil Procedure – CCP § 425.55 – Codes – FindLaw, accessed on January 12, 2026

- The Rising Tide of ADA Website Accessibility Litigation: 2025 Insights | DarrowEverett LLP, accessed on January 12, 2026

- Judge tosses suit against Potter Handy, but challenges to firm’s ADA case filings continue, accessed on January 12, 2026

- Fee Award Against Disability-Access Law Firm Is Reversed – Metropolitan News-Enterprise, accessed on January 12, 2026

- Bill Text: CA AB539 | 2023-2024 | Regular Session | Amended – LegiScan, accessed on January 12, 2026

- High-Frequency Litigation: Framing the Narrative of ADA Actions – Columbia Journal of Law & Social Problems, accessed on January 12, 2026

- UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT – GovInfo, accessed on January 12, 2026

- This Week at the Ninth: Supplemental Jurisdiction Declined | Morrison & Foerster LLP, accessed on January 12, 2026

- VO V. CHOI – Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals, accessed on January 12, 2026

- Ninth Circuit Weighs in On Website Accessibility Obligations – FordHarrison, accessed on January 12, 2026

- Robles v. Domino’s Pizza, LLC, No. 17-55504 (9th Cir. 2019) – Justia Law, accessed on January 12, 2026

- Robles v. Domino’s Settles After Six Years of Litigation – ADA Title III, accessed on January 12, 2026

- California Court Of Appeal’s Midvale Decision Opens The Floodgates For More Website Accessibility Lawsuits | ADA Title III, accessed on January 12, 2026

- Website Accessibility Lawsuits Continue to Trend Up – Hanson Bridgett LLP, accessed on January 12, 2026

- Martinez v. Cot’n Wash, Inc. :: 2022 – Justia Law, accessed on January 12, 2026

- CA Court shuts down website accessibility claims for online-only businesses, accessed on January 12, 2026

- California Court Holds Digital-Only Websites Do Not Qualify As “A Place of Public Accommodation” Under The Unruh Act, accessed on January 12, 2026

- DOJ to Revisit Web Accessibility Rule, Aiming to Reduce Implementation Costs for Counties, accessed on January 12, 2026

- Digital Accessibility Under Title III of the ADA: Recent Developments and Risk Mitigation Best Practices, accessed on January 12, 2026

- WCAG 2 Overview | Web Accessibility Initiative (WAI) – W3C, accessed on January 12, 2026

- Web Content Accessibility Guidelines (WCAG) Overview, accessed on January 12, 2026

- WCAG 101: Understanding the Web Content Accessibility Guidelines, accessed on January 12, 2026

- The Rise Of The Self-Tapping Website? State Wiretapping Class Actions Take Off After Two Recent Circuit Court Decisions | ArentFox Schiff – JDSupra, accessed on January 12, 2026

- 2024 California Penal Code, TITLE 15, PART 1, CHAPTER 1.5 – Invasion of Privacy, accessed on January 12, 2026

- LensCrafters class action alleges company secretly wiretaps website chats, accessed on January 12, 2026

- LICEA v. AMERICAN EAGLE OUTFITTERS INC (2023) – FindLaw Caselaw, accessed on January 12, 2026

- California Code, Penal Code – PEN § 638.51 – Codes – FindLaw, accessed on January 12, 2026

- CIPA 638.51 – Pen Register / Trap and Trace – Shay Legal APC, accessed on January 12, 2026

- TikTok Pixel CIPA Claims Are Running on Borrowed Time | JD Supra, accessed on January 12, 2026

- TikTok Pixel CIPA Claims Are Running on Borrowed Time – Klein Moynihan Turco, accessed on January 12, 2026

- Green Light for CIPA: New Federal Court Ruling Fuels Digital Tracking Class Actions, accessed on January 12, 2026

- ORDER by Judge Noel Wise GRANTING 16 Motion to Dismiss. Motion Hearing and Initial Case Management Conference set for June 25, 2 – U.S. Case Law, accessed on January 12, 2026

- The Myth of Accessibility Overlays – Tamman Inc, accessed on January 12, 2026

- Widgets Archives /Tag – 216digital, accessed on January 12, 2026

- Accessibility Overlays – All Sizzle, No Steak: Karl Groves – Equalize Digital, accessed on January 12, 2026

- Overlays and Plugins Aren’t the Answer to Accessibility | Design Domination, accessed on January 12, 2026

- The Truth About Web Accessibility Overlays – Gratzer Graphics, accessed on January 12, 2026

- Guidance on Web Accessibility and the ADA – ADA.gov, accessed on January 12, 2026

- A Status Update on Hotel Reservations Website Lawsuits | ADA Title III, accessed on January 12, 2026

- Disability Access Lawsuits Migrate From Federal To State Court – SFGATE, accessed on January 12, 2026

- The disability-rights personal-injury “crossover” case in public accommodations, accessed on January 12, 2026