Why California Courts (and the FTC) Are Punishing Quick Fixes

Executive Summary

The digital accessibility landscape in the United States has undergone a fundamental transformation in the years 2024 and 2025, shifting from a period of unregulated technological experimentation to an era of strict judicial and federal enforcement. For nearly a decade, businesses sought to mitigate the rising tide of Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) lawsuits by deploying accessibility overlays—automated toolbars and widgets powered by artificial intelligence (AI) that promised instant, low-cost compliance with the Web Content Accessibility Guidelines (WCAG). This report argues that this strategy has not only failed but has mutated into a distinct liability known as the “Overlay Trap,” a phenomenon where organizations, in an attempt to shield themselves from litigation, inadvertently increase their exposure to regulatory action, civil lawsuits, and search engine penalties.

The defining event of this new era occurred in early 2025 when the Federal Trade Commission (FTC) finalized a consent order against accessiBe, a leading overlay vendor, prohibiting deceptive claims regarding AI-driven compliance.1 This federal intervention effectively dismantled the marketing narrative that had sustained the overlay industry. Simultaneously, California courts have become the primary theater for digital civil rights litigation. With federal judges increasingly remanding cases to state courts, the California Unruh Civil Rights Act has weaponized digital inaccessibility, driving a 37% surge in lawsuits—a significant portion of which specifically target websites utilizing “quick fix” tools.2

This comprehensive report provides an exhaustive analysis of the jurisprudential shifts, technical failures, and financial risks associated with the use of accessibility overlays in the current regulatory environment. It explores the intersection of legal liability and search engine optimization (SEO), particularly in the context of Generative Engine Optimization (GEO), arguing that the very tools used to feign compliance are actively degrading digital visibility and user experience.

Part I: The Regulatory Tsunami and Federal Intervention

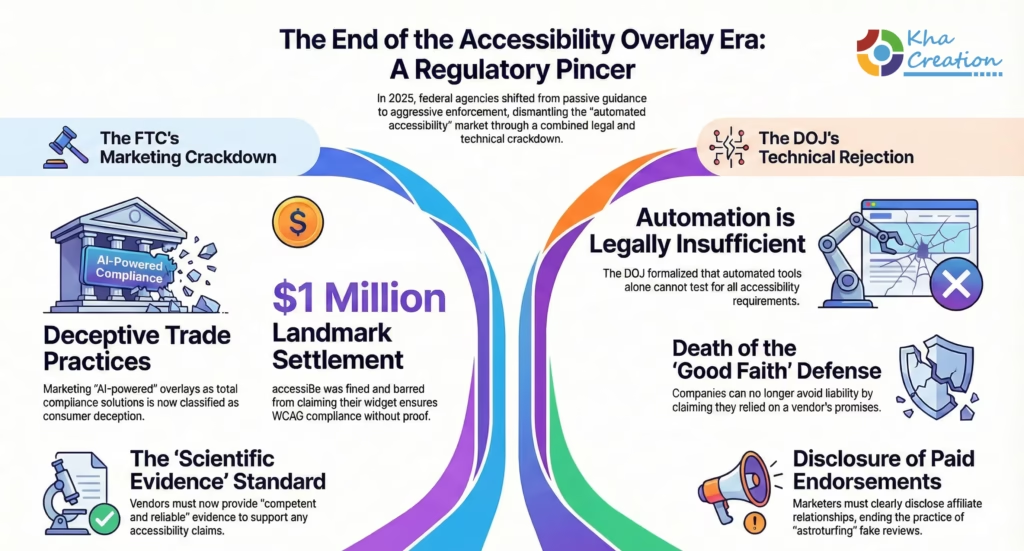

The era of unchecked claims regarding automated web accessibility effectively ended in 2025. The shift was not gradual; it was a decisive regulatory strike that reclassified the marketing of accessibility overlays from “puffery” to “deceptive trade practices.” This section analyzes the federal government’s pivot toward strict enforcement and its implications for corporate governance.

1. The Federal Trade Commission’s “Operation AI Comply”

For years, the Department of Justice (DOJ) maintained a relatively passive stance on specific web accessibility technologies, issuing guidance but refraining from endorsing or banning specific tools. This vacuum allowed private vendors to proliferate, marketing “AI-powered” solutions that claimed to solve the complex problem of digital inclusion with a single line of JavaScript code. In 2025, the FTC stepped into this void with “Operation AI Comply,” a sweeping enforcement action targeting companies that used the hype surrounding artificial intelligence to deceive consumers.4

1.1 The accessiBe Consent Order: A Legal Landmark

On April 22, 2025, the FTC approved a final consent order against accessiBe, one of the most visible and aggressive vendors in the overlay market.1 The significance of this order extends far beyond the specific company involved; it establishes a new federal standard for truth in advertising regarding accessibility technology.

The complaint alleged that accessiBe’s marketing claims—specifically that its “accessWidget” could make any website compliant with the ADA and WCAG—were false, misleading, and unsubstantiated.1 The FTC’s investigation revealed that the tool could not, in fact, automatically remediate complex accessibility barriers, a finding that aligned with years of criticism from technical experts and disability advocates.

The resulting settlement imposed strict behavioral remedies that serve as a warning to the entire software-as-a-service (SaaS) industry. First, the order required a financial payment of $1 million.1 While this amount might appear negligible compared to the vendor’s revenue, the injunctive relief attached to the order is devastating to the overlay business model. The company is now permanently barred from representing that its automated products can make any website WCAG-compliant or ensure continued compliance unless it possesses “competent and reliable scientific evidence” to support such claims.1

This “competent and reliable evidence” standard is the linchpin of the FTC’s new approach. In the context of web accessibility, generating such evidence for an automated tool is technically improbable, if not impossible, given the subjective nature of many WCAG success criteria (e.g., determining whether an image description is meaningful). By setting this evidentiary bar, the FTC has effectively prohibited the core marketing claim that drove the adoption of overlays by thousands of small and medium-sized businesses.

1.2 The Prohibition on Deceptive Endorsements

Beyond efficacy claims, the FTC settlement addressed the “astroturfing” practices common in the overlay industry. The complaint detailed how the vendor had allegedly manipulated third-party reviews and articles to appear as independent opinions from impartial users or experts.1

The consent order prohibits the company from misrepresenting that an endorser is an independent user or that a review is an objective assessment when a material connection exists. This creates a ripple effect for the digital marketing ecosystem. Affiliate marketers, web design agencies, and bloggers who previously promoted these tools in exchange for commissions must now disclose those relationships clearly, or they too risk violating FTC guidelines. For businesses evaluating vendors, this means that “independent” reviews found online can no longer be trusted at face value, necessitating a deeper level of due diligence.

2. The DOJ’s Stance on “Quick Fixes”

While the FTC focused on consumer protection and advertising, the Department of Justice (DOJ) clarified its position on the technical adequacy of automated tools through its rule-making process for ADA Title II (State and Local Governments). Although Title II applies to public entities, the DOJ’s technical determinations often inform the interpretation of Title III (Public Accommodations) by federal courts.

In its guidance accompanying the new web accessibility rule, the DOJ emphasized that automated testing and remediation alone are insufficient to ensure compliance. The guidance explicitly states that “you won’t be able to use automated testing tools alone, because those tools can’t test for all aspects of accessibility”.7 By formalizing this position, the DOJ has provided plaintiffs’ attorneys with a powerful citation. If the federal government acknowledges that automation cannot test for all issues, it follows logically that automation cannot fix all issues.

This regulatory alignment between the FTC and DOJ creates a pincer movement against the overlay industry. The FTC attacks the marketing claims, while the DOJ undermines the technical validity. For corporate defendants, this removes the “good faith” defense often used in litigation—the argument that the business relied on a reputable vendor’s promise of compliance is no longer tenable when federal agencies have publicly debunked those promises.

Part II: The California Crucible – The Unruh Act and State Court Warfare

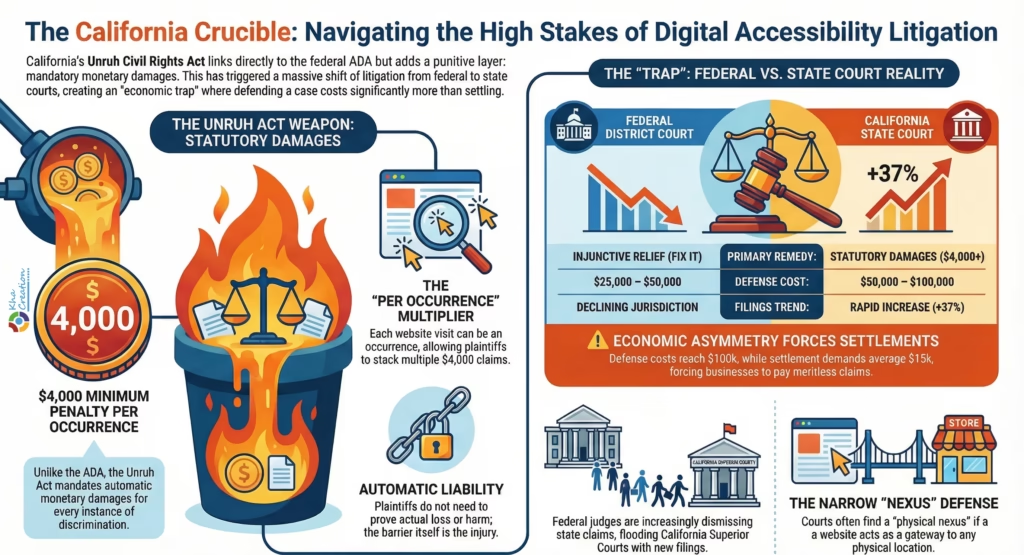

While federal agencies address the macro-level regulatory environment, the actual battlefield for digital accessibility lawsuits is the state of California. In 2024 and 2025, California solidified its position as the global epicenter of accessibility litigation, driven by the unique and punitive mechanics of the Unruh Civil Rights Act. This section analyzes why California courts have become the “trap” for businesses relying on overlays.

3. The Unruh Civil Rights Act: Weaponizing Statutory Damages

The Unruh Civil Rights Act (California Civil Code § 51) is a broad anti-discrimination statute that predates the ADA. However, a 1992 amendment fundamentally linked the two laws, stating that “a violation of the right of any individual under the Americans with Disabilities Act of 1990 shall also constitute a violation of this section”.8

This linkage is critical because the remedies available under the two laws are drastically different.

- ADA (Federal): Remedies are limited to injunctive relief (a court order to fix the website) and the recovery of reasonable attorney’s fees. There are no monetary damages payable to the plaintiff.

- Unruh Act (State): This act allows for the recovery of statutory damages. The law mandates a minimum penalty of $4,000 per occurrence of discrimination.9

3.1 The “Per Occurrence” Multiplier

The phrase “per occurrence” is the engine of the litigation economy in California. In the context of a physical business, an occurrence is a visit. In the digital realm, an occurrence can be interpreted as a visit to a website. If a plaintiff visits a website three times in a week and encounters barriers each time, the statutory liability is theoretically $12,000. While courts often limit this to deter abuse, the threat of piled-up statutory damages provides immense leverage for plaintiffs’ attorneys during settlement negotiations.

Furthermore, unlike other torts that require a showing of actual loss or harm (actual damages), statutory damages under Unruh are automatic upon the finding of a violation. The plaintiff does not need to prove they lost money or suffered emotional distress; the mere existence of the barrier is the injury.11

4. The Federal Exodus: Why Cases are Flooding State Courts

A major procedural shift occurred in 2024 and 2025 regarding where these cases are heard. Historically, plaintiffs filed in federal court, alleging an ADA violation and attaching a “supplemental” Unruh Act claim. Federal judges have “supplemental jurisdiction” to hear state claims that arise from the same facts as a federal claim.

However, federal judges in California, particularly in the Central and Northern Districts, began to recognize that high-frequency litigants were using the federal court system primarily to extract state-law damages. In response, federal judges started declining supplemental jurisdiction over the Unruh claims, dismissing them without prejudice and forcing plaintiffs to refile in state court.12

4.1 The Consequence of State Court Litigation

This procedural rejection has led to a massive migration of cases to California Superior Courts (state courts). This is disadvantageous for defendants for several reasons:

- Pleading Standards: Federal courts (under Twombly/Iqbal standards) require detailed factual allegations to survive a motion to dismiss. California state courts have more lenient pleading standards, making it harder to get a weak case dismissed at the early “demurrer” stage.13

- Summary Judgment: It is generally more difficult and expensive to win summary judgment in California state court than in federal court.

- Discovery Burden: The discovery process in state court can be more protracted and costly.

The result is that the cost of defense in state court often exceeds the cost of settlement by a factor of three or four. A typical defense through trial might cost $50,000 to $100,000, while a settlement demand might be $15,000.14 This economic asymmetry forces businesses to settle even meritless claims, reinforcing the “trap.”

5. The “Nexus” Theory and the “Virtual” Business Defense

One of the few defenses available to businesses in California has been the argument that the ADA (and thus Unruh) applies only to physical “places of public accommodation,” and therefore purely online businesses are exempt.

5.1 The Martinez and Thi E-Commerce Rulings

In 2023 and 2024, California Courts of Appeal issued rulings in Martinez v. Cot’n Wash, Inc. and Martin v. Thi E-Commerce, LLC. These courts held that for a website to be subject to the ADA, there must be a “nexus” (connection) to a physical place of public accommodation.15 These rulings were initially hailed as a victory for online-only retailers.

5.2 The Limits of the Defense

However, by 2025, it became clear that this defense is narrower than anticipated.

- The Physical Nexus Trap: Most businesses are not “purely” virtual. A restaurant with online ordering, a retailer with a showroom, or a brand with pop-up shops all have a physical nexus. Courts have found that if the website serves as a “gateway” to the physical location (e.g., checking hours, viewing menus, buying tickets), the ADA applies.13

- Intentional Discrimination: Plaintiffs have adapted their tactics. Even if the ADA doesn’t apply to a virtual business, plaintiffs can sue under Section 51(b) of the Unruh Act, which prohibits intentional discrimination. While harder to prove, plaintiffs argue that the installation of an ineffective overlay demonstrates “knowledge” of the inaccessibility, and the refusal to fix the underlying code demonstrates “intent”.19

- San Francisco Superior Court Rulings: In jurisdictions like San Francisco, judges have been skeptical of broad dismissals based on the Martinez precedent, often allowing cases to proceed to factual discovery regarding the nature of the business’s operations.20

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Legal Venues for Accessibility Claims

| Feature | Federal District Court (California) | California Superior Court (State) |

| Primary Claim | ADA Title III | Unruh Civil Rights Act |

| Damages Available | Injunctive Relief, Attorney’s Fees | Statutory Damages ($4,000+), Fees |

| Dismissal Standard | High (Twombly/Iqbal); Rule 12(b)(6) | Low (Demurrer); Fact-pleading |

| Jurisdictional Trend | Declining supplemental jurisdiction | Rapid increase in filings (+37%) |

| Defense Cost | High ($25k-$50k) | Very High ($50k-$100k) |

| Settlement Pressure | Moderate | Extreme |

Part III: The Technical Paradox – Why AI Fails the Reality Test

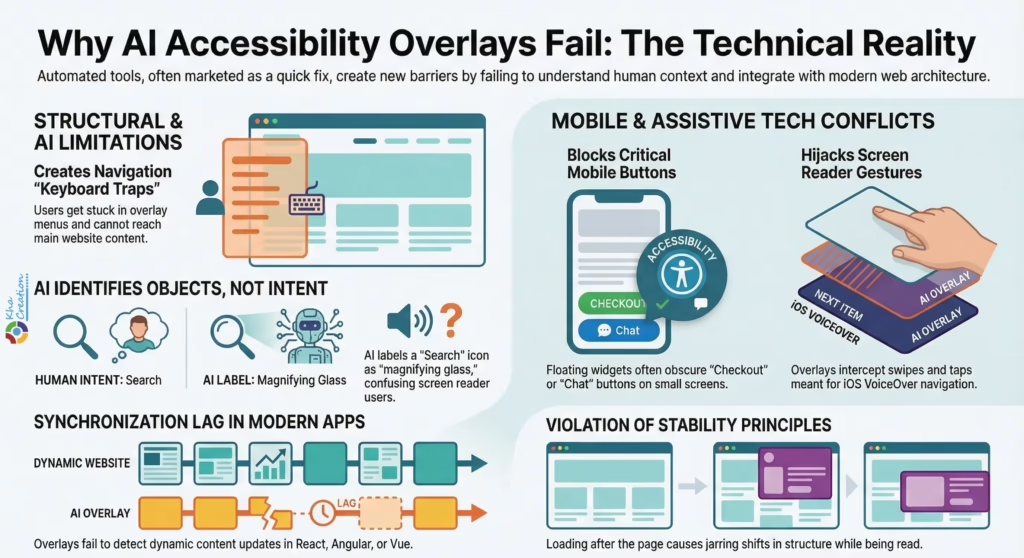

To understand why courts and regulators are rejecting overlays, one must look beyond the law to the technology itself. The failure of overlays is not a legal technicality; it is a structural inability of the technology to meet the requirements of human interaction. This section provides a deep technical autopsy of why “AI” cannot fix the web.

6. The “Shadow DOM” and the Accessibility Tree

The fundamental flaw of the overlay approach lies in how it interacts with the browser. When a user visits a website, the browser parses the HTML code into a structure called the Document Object Model (DOM). Assistive technologies, like screen readers (JAWS, NVDA, VoiceOver), do not read the DOM directly. Instead, they interact with the Accessibility Tree, a simplified version of the DOM that strips away visual data and presents the semantic structure (headings, buttons, links) to the user.

6.1 The Overlay Mechanism

Overlays typically work by injecting a script that attempts to modify the DOM on the fly. Some create a “Shadow DOM”—an encapsulated subtree of DOM elements—to render the widget and its menu without being affected by the site’s main CSS.23

- The Conflict: Screen readers often struggle to navigate between the main DOM and the Shadow DOM. This often results in “keyboard traps,” where a blind user pressing the ‘Tab’ key gets stuck cycling through the overlay’s menu and cannot reach the main content of the website. This is a direct violation of WCAG Criteria 2.1.2 (No Keyboard Trap).

- Timing Issues: Overlays load asynchronously (after the page starts rendering). A screen reader might begin reading the page before the overlay has finished its “repairs.” This leads to a jarring experience where the page structure changes while the user is trying to read it, violating WCAG 2.2 (Stability) principles.

7. The Limits of Artificial Intelligence in Context

The “AI” marketed by overlay vendors is primarily based on image recognition and heuristic analysis. While impressive in isolation, it lacks the semantic understanding necessary for accessibility.

7.1 The Alt-Text Failure

WCAG requires that images have “equivalent” alternative text. This is a subjective, context-dependent requirement.

- Example: An image of a magnifying glass.

- Context A (Search Bar): The alt-text should be “Search.”

- Context B (Article about Sherlock Holmes): The alt-text might be “Vintage magnifying glass.”

- Context C (Decorative Icon): The alt-text should be null (“”) so the screen reader ignores it.

- The AI Failure: Automated tools often identify the object (“magnifying glass”) but cannot determine the intent. An overlay might label a search button as “magnifying glass,” leaving a blind user confused about the button’s function. The “Overlay Fact Sheet” notes that automated repair of text alternatives is “not reliable”.23

7.2 State Management and Modern Frameworks

The modern web is built on dynamic JavaScript frameworks like React, Angular, and Vue. These Single Page Applications (SPAs) update content dynamically without reloading the page.

- The Sync Problem: When a React app updates the DOM (e.g., loading new products as the user scrolls), the overlay often fails to detect the change immediately. The new content renders without the overlay’s “fixes,” leaving it inaccessible. The overlay is effectively always one step behind the user interaction, creating a perpetually broken experience for assistive technology users.23

8. Mobile Incompatibility: The Achilles Heel

With over 60% of web traffic occurring on mobile devices, mobile accessibility is paramount. Overlays are notoriously poor performers in the mobile environment, a fact that has driven a significant portion of recent litigation.24

8.1 The “Intrusive Interstitial” of Accessibility

On a desktop screen, an overlay widget is a small icon in the corner. On a mobile screen, that same widget can obscure critical interface elements.

- Touch Target Interference: WCAG 2.5.5 recommends touch targets be at least 44×44 pixels. Overlays often float over the “Checkout” or “Chat” buttons. If a user tries to tap “Checkout” and hits the overlay instead, the site is functionally broken.

- VoiceOver Conflicts: iOS VoiceOver uses specific gestures (swipes and taps) to navigate. Overlay widgets often intercept these touch events to open their own menus. This conflict can cause VoiceOver to become unresponsive or announce elements incorrectly. Reports indicate that overlays can cause VoiceOver to announce “unpronounceable” strings instead of star ratings, rendering reviews inaccessible.23

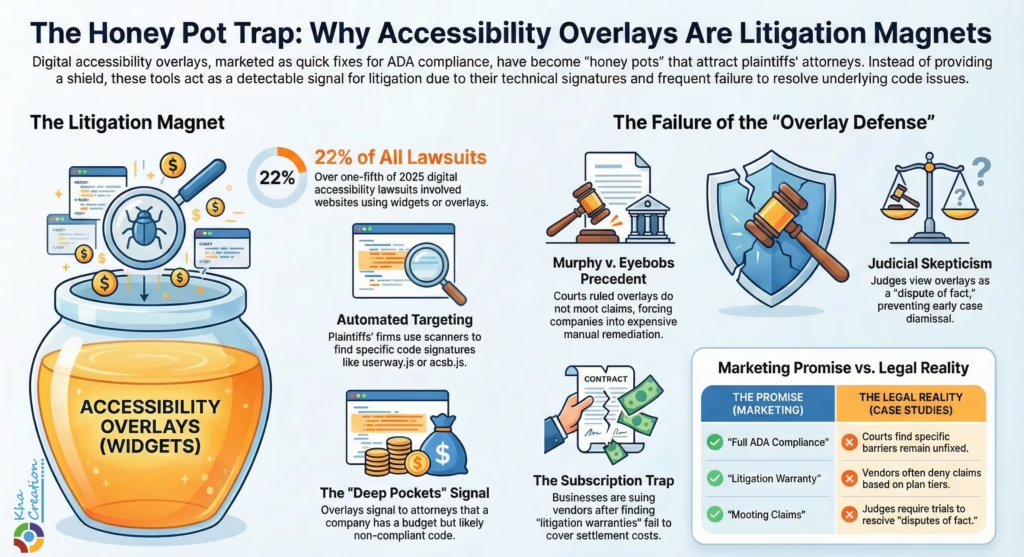

Part IV: The “Honey Pot” Effect and Case Studies

The most perverse outcome of the overlay era is that the tools sold as “protection” have become “targets.” This section analyzes the data supporting the “Honey Pot” theory and details specific cases where the overlay defense collapsed.

9. The Data: Overlays as Litigation Magnets

Statistical analysis of 2024 and 2025 lawsuit filings confirms a strong correlation between overlay usage and litigation.

- Targeting Efficiency: Plaintiffs’ law firms utilize automated scanning tools to identify potential defendants. These scanners look for specific code signatures. The presence of an overlay script (e.g., userway.js, acsb.js) is an easily detectable signature.

- The Signal: To a plaintiff’s attorney, an overlay signals two things:

- Deep Pockets/Budget: The company has a budget for accessibility and is aware of the issue.

- Likely Non-Compliance: Since experts know overlays cannot fix all issues, the presence of one suggests the underlying code is likely full of WCAG violations that the overlay is masking.

- The Statistics: In the first half of 2025, over 22% of all digital accessibility lawsuits filed involved websites using accessibility widgets or overlays.26 Considering that overlays are used by a minority of all websites, this represents a massive statistical over-representation.

10. Landmark Case Studies

10.1 Murphy v. Eyebobs (Western District of Pennsylvania)

This case is frequently cited as the death knell for the “overlay defense.”

- The Facts: The plaintiff, Anthony Murphy, sued Eyebobs, an eyewear retailer that used the accessiBe overlay. Murphy alleged that despite the overlay, he could not navigate the site using his screen reader.

- The Defense: Eyebobs moved to dismiss, arguing that the overlay rendered the site accessible and mooted the claim.

- The Ruling: The court denied the motion to dismiss, allowing the case to proceed. The judge found that the plaintiff’s allegations of specific barriers (which the overlay failed to fix) were sufficient to state a claim.28

- The Settlement: Eyebobs was forced to settle. The consent decree was particularly damning for the overlay industry: it required Eyebobs to remove the overlay and engage in manual remediation to meet WCAG 2.1 AA standards. It also mandated the hiring of an accessibility coordinator and regular user testing—precisely the rigorous process the overlay was supposed to avoid.30

10.2 Bloomsybox v. UserWay (Class Action)

If Eyebobs showed the failure of defense, Bloomsybox showed the backlash against vendors.

- The Narrative: Bloomsybox, a flower delivery company, purchased the UserWay widget, relying on marketing claims of “full ADA compliance” and a “$1,000,000 litigation warranty.”

- The Betrayal: After installing the tool, Bloomsybox was sued. When they turned to UserWay for the promised protection, they were allegedly told they didn’t qualify because they were on a monthly plan, not an annual one. Even after upgrading, the “legal support” consisted of generic PDFs, and UserWay refused to cover the settlement costs.31

- The Lawsuit: Bloomsybox sued UserWay in a class action, alleging breach of contract, fraud, and violation of the Delaware Consumer Fraud Act. This case highlights the “Subscription Trap”: businesses pay for a shield that turns out to be made of paper.32

10.3 San Francisco Superior Court Trends

In San Francisco, defense attorneys report that judges are increasingly hostile to the argument that a widget makes a website “accessible.”

- Judicial Skepticism: In consolidated proceedings and case management conferences, judges have noted that if a plaintiff claims they couldn’t use the site, the mere presence of a tool doesn’t disprove that claim. It creates a “dispute of fact” that requires a trial to resolve.

- The Cost of “Fact”: Once a judge decides there is a “dispute of fact,” the case cannot be dismissed early. The cost to prove the fact (that the site works) involves hiring expert witnesses to conduct forensic analysis of the overlay’s performance. This costs tens of thousands of dollars, forcing the defendant to settle.14

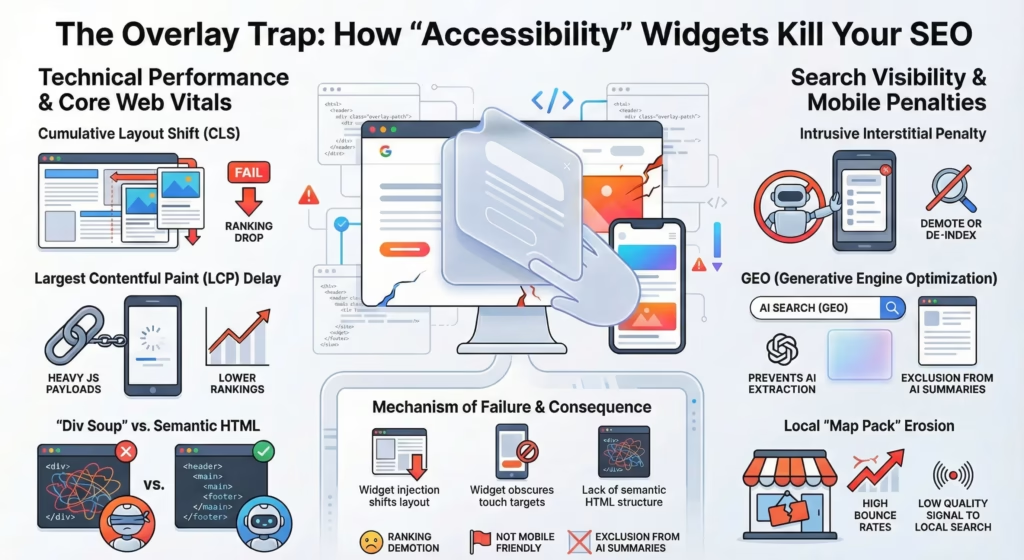

Part V: The Hidden Cost – SEO, GEO, and Search Visibility

While legal risks grab the headlines, the “Overlay Trap” inflicts silent, long-term damage on a company’s digital marketing performance. In 2025, the synergy between accessibility and Search Engine Optimization (SEO) is stronger than ever. Furthermore, the rise of Generative Engine Optimization (GEO)—optimizing for AI search engines like ChatGPT Search and Google Gemini—has made clean, semantic code a prerequisite for visibility.

11. Core Web Vitals and The Performance Penalty

Google’s ranking algorithm prioritizes “Core Web Vitals,” a set of metrics measuring user experience. Overlays negatively impact all three primary vitals.

11.1 Cumulative Layout Shift (CLS)

CLS measures visual stability. Does the page jump around as it loads?

- The Overlay Effect: Overlays are third-party scripts that inject elements into the DOM. Often, the widget icon appears after the rest of the page, or the overlay “adjusts” fonts and spacing after the initial render. This causes the page layout to shift visibly.

- The Penalty: Google penalizes sites with high CLS scores. By using an overlay to “fix” accessibility, businesses are actively down-ranking their websites in search results.34

11.2 Largest Contentful Paint (LCP) and Load Time

LCP measures how long it takes for the main content to load.

- Script Bloat: Overlays add heavy JavaScript payloads. On mobile networks (3G/4G), this extra code delays the rendering of the main content.

- The Impact: Slower load times lead to higher bounce rates and lower rankings. Google explicitly advises against lazy-loading primary content in a way that depends on user interaction, yet many overlays function precisely this way.36

12. Mobile-First Indexing and Intrusive Interstitials

Google uses “Mobile-First Indexing,” meaning it ranks a site based on its mobile version.

12.1 The “Intrusive Interstitial” Penalty

Google explicitly downgrades sites that use “intrusive interstitials”—pop-ups that cover the main content immediately upon loading.38

- The Accessibility Irony: Many overlays, in an attempt to be “helpful,” open a large accessibility menu or pop-up on mobile devices to offer options like “increase font size.”

- The Bot’s View: Googlebot views this as an obstruction. It sees a pop-up blocking the content and applies the “Intrusive Interstitial” penalty, effectively de-indexing or demoting the page for mobile searchers.40

13. Generative Engine Optimization (GEO) and Semantic Code

As search shifts from keywords to AI-driven answers (GEO), the structure of data becomes as important as the content.

- Semantic HTML vs. JavaScript Patches: AI models (LLMs) ingest the HTML structure to understand the relationship between concepts. A native <h1> tag tells the AI “this is the main topic.”

- The Overlay Problem: Overlays often leave the underlying code as a mess of <div> soups (unsemantic code) and try to “paint” accessibility on top visually. The AI crawler, looking at the code, sees a disorganized structure. It may fail to extract the correct entities or answers, causing the business to disappear from AI-generated summaries.

- Local SEO: For local businesses, accessibility is an indirect ranking signal. High bounce rates from disabled users signal to Google that the “Near Me” result is low quality, pushing the business down in the Local Pack.41

Table 2: The SEO/GEO Impact Matrix

| Metric | Mechanism of Failure | Consequence |

| Core Web Vitals (CLS) | Widget injection shifts layout | Ranking Demotion |

| Mobile Usability | Widget obscures touch targets | “Not Mobile Friendly” Flag |

| Intrusive Interstitials | Accessibility menu covers content | Mobile Ranking Penalty |

| GEO (AI Search) | Lack of semantic HTML structure | Exclusion from AI Summaries |

| Local SEO | High bounce rate from disabled users | Lower “Map Pack” Ranking |

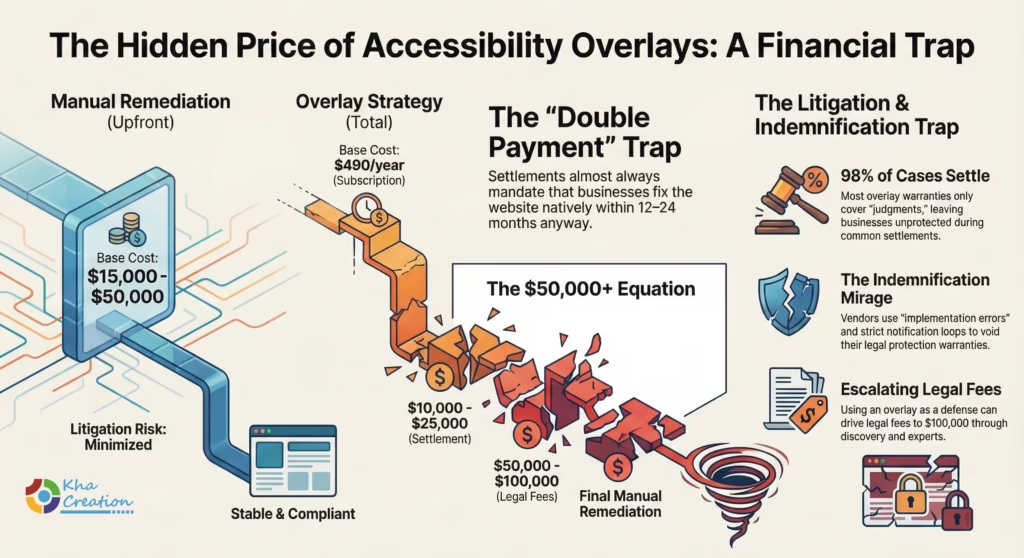

Part VI: The Economic Reality – The “Cheap” Option is the Most Expensive

The primary driver for overlay adoption is cost. A full manual remediation of a complex e-commerce site can cost between $15,000 and $50,000, whereas overlays charge a subscription of $49 to $490 per month. However, this calculation is fundamentally flawed when litigation risk is factored in.

14. The Defense vs. Settlement Calculus

Data from 2024-2025 litigation reveals the true cost of the overlay strategy.

- Average Settlement: $10,000 – $25,000. This is the “go away” money paid to the plaintiff.14

- Defense Costs: If a business tries to fight using the overlay as a defense, they face motions to dismiss, discovery, and expert witnesses. Legal fees can quickly escalate to $50,000 – $100,000.14

- Double Payment: Crucially, the settlement almost always mandates that the business fix the website natively within 12-24 months.

- The Equation:

$$Cost_{Total} = Cost_{Overlay} + Cost_{Settlement} + Cost_{LegalDefense} + Cost_{Remediation}$$

A business that spent $15,000 up front on remediation avoids the middle two terms. A business that buys a $490/year overlay often ends up paying all four terms, totaling $50,000+.

15. The Indemnification Mirage

Businesses often believe their vendor contracts protect them. The Bloomsybox allegations suggest otherwise.

- “Judgments” vs. “Settlements”: Many warranties only cover “legal judgments.” Since 98% of cases settle, the vendor never has to pay.

- Procedural Hoops: Vendors may require immediate notification, use of their specific counsel, or proof that the widget was “implemented correctly” (which they can claim was not done) to void the warranty.31

Conclusion and Strategic Recommendations

The events of 2025 represent a market correction. The accessibility overlay industry, fueled by the promise of AI magic, has collided with the rigid realities of federal consumer protection, California civil rights law, and the technical requirements of the modern web. The FTC’s order against accessiBe and the rising tide of overlay-specific lawsuits in California send a singular message: there is no algorithmic shortcut to civil rights.

For businesses, the “Overlay Trap” is a paradox—an attempt to reduce risk that actively generates it. The data is clear: overlays fail to prevent lawsuits, fail to provide technical access, fail to withstand judicial scrutiny, and actively degrade search engine visibility. As California courts continue to punish “quick fixes” through the mechanism of statutory damages, and as the FTC polices the marketing of these tools, the only viable path forward is a return to foundational web development best practices.

Strategic Recommendations for 2025-2026:

- Immediate Decoupling: Organizations utilizing accessibility overlays should plan for their removal. The legal risk of the “Honey Pot” effect now outweighs any theoretical compliance benefit.

- Native Remediation: Budget for “Shift Left” accessibility. Incorporate WCAG 2.2 principles into the design and development phase. Use semantic HTML.

- Manual Audit: Engage third-party experts to conduct manual audits (including screen reader testing) to establish a baseline of true compliance.

- Vendor Governance: Demand VPATs (Voluntary Product Accessibility Templates) from all third-party software vendors. Ensure contracts include indemnification clauses that specifically cover ADA claims including settlements.

- Transparency: Publish an Accessibility Statement that honestly reflects the site’s current status and provides a working feedback mechanism (phone/email) for users to report barriers. This feedback loop is often the most effective defense against litigation.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ)

Q1: If I use an accessibility overlay, am I safe from ADA lawsuits?

No. In fact, data suggests you may be more likely to be sued. In the first half of 2025, over 22% of all digital accessibility lawsuits targeted websites using overlays.27 Plaintiffs’ attorneys use the presence of an overlay code as a “signal” that the website likely has underlying accessibility issues and that the business has the budget to pay a settlement.

Q2: Why did the FTC fine accessiBe $1 million?

The FTC settled with accessiBe for deceptive advertising practices. The Commission alleged that accessiBe made unsubstantiated claims that its AI tool could make any website WCAG compliant. The order bars the company from making these compliance claims without competent scientific evidence—evidence that the technical community generally agrees does not exist for automated tools.1 The FTC also penalized the company for using “fake” reviews to boost its reputation.

Q3: What is the difference between the ADA and the California Unruh Act regarding websites?

The ADA is a federal law that generally allows for injunctive relief (fixing the site) and attorney’s fees, but not monetary damages for the plaintiff. The California Unruh Civil Rights Act incorporates the ADA but adds statutory damages of at least $4,000 per occurrence of discrimination.8 This financial incentive is why so many digital accessibility lawsuits are filed in, or removed to, California state courts.

Q4: Can AI ever make a website fully accessible?

Currently, no. While AI can help with certain tasks (like suggesting alt-text or checking contrast), it cannot understand context. For example, AI cannot tell if an image is decorative or informational with 100% accuracy, nor can it navigate complex, custom interactive flows (like a checkout process) without human testing. The “Overlay Fact Sheet,” signed by hundreds of experts, states that automated tools can cover only about 30% of WCAG criteria.24

Q5: My overlay vendor promises “Litigation Support.” Does that protect me?

Recent litigation, such as Bloomsybox v. UserWay, challenges the value of these promises. Allegations suggest that vendors may deny support based on technicalities (e.g., subscription type) or provide only generic guides rather than actual legal defense or financial indemnification.32 A warranty is only as good as the terms enforcing it, and many exclude settlements, which is how 98% of cases end.

Q6: How does an overlay affect my SEO?

Overlays can negatively impact SEO in three ways:

- Core Web Vitals: They can increase “Cumulative Layout Shift” (CLS) and “Largest Contentful Paint” (LCP) times, hurting rankings.34

- Mobile Penalties: Google penalizes “intrusive interstitials” that block content; many overlay menus behave this way on mobile.40

- Bounce Rates: If the overlay makes the site difficult to use, visitors leave quickly, signaling poor quality to Google.41

Q7: What should I do if I currently have an overlay installed?

The consensus among risk management experts is to:

- Remove the Overlay: Stop the immediate signal that you are using a “quick fix” and prevent technical interference with screen readers.

- Conduct an Audit: Hire a professional to conduct a manual audit of your site against WCAG 2.1 AA standards.

- Remediate the Code: Fix the underlying HTML and CSS.

- Publish a Statement: Post an accessibility statement providing a contact method for users encountering barriers. This demonstrates a good-faith commitment to access.43

Q8: Are “virtual” businesses without a physical store subject to the ADA in California?

This is a complex and evolving area. While recent appellate rulings (Martinez) suggest that purely virtual businesses are not “public accommodations” under the ADA, many lawsuits successfully allege a “nexus” to a physical location (e.g., a warehouse, a showroom, or even a third-party retailer selling the goods).13 Furthermore, plaintiffs are finding alternative legal theories under the Unruh Act (Intentional Discrimination) to target virtual businesses. It is legally risky to assume exemption based solely on lacking a storefront.

References/ Works cited

- FTC Approves Final Order Requiring accessiBe to pay $1 Million …, accessed on January 19, 2026

- Website Accessibility in 2025: Lessons from 2024 Lawsuit Trends – AudioEye, accessed on January 19, 2026

- 2025 Mid-Year Report: ADA Website Accessibility Lawsuits Surge 37% as Litigation Expands Nationwide – PR Newswire, accessed on January 19, 2026

- FTC Announces Crackdown on Deceptive AI Claims and Schemes, accessed on January 19, 2026

- Misleading Artificial Intelligence Claims by Marketer of Website Accessibility Widget Lead to $1 Million FTC Settlement | Consumer Financial Services Law Monitor, accessed on January 19, 2026

- FTC Order Requires Online Marketer to Pay $1 Million for Deceptive Claims that its AI Product Could Make Websites Compliant with Accessibility Guidelines | Federal Trade Commission, accessed on January 19, 2026

- State and Local Governments: First Steps Toward Complying with the Americans with Disabilities Act Title II Web and Mobile Application Accessibility Rule | ADA.gov, accessed on January 19, 2026

- Understanding the California Unruh Act – TPGi – Vispero, accessed on January 19, 2026

- CIVIL RIGHTS AT CALIFORNIA BUSINESSES, accessed on January 19, 2026

- Unruh Civil Rights Act | A Business Compliance Guide – Level Access, accessed on January 19, 2026

- CACI No. 3067. Unruh Civil Rights Act – Damages (Civ. Code, §§ 51, 52(a)) – Justia, accessed on January 19, 2026

- Legal Update: November 2025 – Converge Accessibility, accessed on January 19, 2026

- Legal Update: July 2025 – Converge Accessibility, accessed on January 19, 2026

- Website Accessibility vs. Lawsuit Costs: Save Money Early – AudioEye, accessed on January 19, 2026

- Another California Appellate Court Holds That ADA Does Not Apply to a Virtual Business’s Website – Ogletree, accessed on January 19, 2026

- Websites Are Not A Public Accommodation Under the ADA, Says California Court of Appeals; CA Supreme Court Denies Review Petition | ADA Title III, accessed on January 19, 2026

- California Court of Appeal Narrows Reach of ADA and Unruh Civil Rights Act as They Apply to Ecommerce Businesses – Hunton Andrews Kurth LLP, accessed on January 19, 2026

- Legal Update: May 2025 – Converge Accessibility, accessed on January 19, 2026

- The Unruh Act: Understand the lawsuits and how state and federal regulations could combine to create blockbuster settlements – Deque, accessed on January 19, 2026

- Website Accessibility Lawsuits Continue to Inundate California Courts Despite COVID-19, accessed on January 19, 2026

- San Francisco ADA Lawsuit Defense Info | nklegal.com, accessed on January 19, 2026

- Diana Sandoval v Robert Seidler et al – Santa Barbara Superior Court, accessed on January 19, 2026

- Overlay Fact Sheet, accessed on January 19, 2026

- 4 Reasons Accessibility Overlays Don’t Work – Getfused, accessed on January 19, 2026

- Accessibility Overlay Widgets Attract Lawsuits, accessed on January 19, 2026

- Accessibility Industry Update: August 2025 – QualityLogic, accessed on January 19, 2026

- AI Is Fueling a New Wave of Accessibility Lawsuits, accessed on January 19, 2026

- The Infamous Eyebobs Web Accessibility Lawsuit: Here’s What You Want to Know, accessed on January 19, 2026

- ADA Litigation and Digital Accessibility – Legal Briefings, accessed on January 19, 2026

- The Legal Risks of Using an Overlay – Tamman Inc, accessed on January 19, 2026

- Userway faces class action lawsuit over alleged false accessibility and ADA compliance claims, accessed on January 19, 2026

- UserWay Class-action Lawsuit | Design Domination – Creative Boost, accessed on January 19, 2026

- Four Things You Need to Know About Website Accessibility Claims in California [Alert] – Cozen O’Connor, accessed on January 19, 2026

- Accessibility and SEO: Improving Web Visibility and Usability – BrowserStack, accessed on January 19, 2026

- How Core Web Vitals Impact Mobile vs Desktop SEO – Upward Engine, accessed on January 19, 2026

- Lazy Loading vs Eager Loading: Optimize Resource Delivery for Performance – Maelstrom Web Services, accessed on January 19, 2026

- 5️ Techniques to Lazy-Load Website Content for Better SEO & User Experience, accessed on January 19, 2026

- Intrusive Interstitials and SEO: A Deep Dive Into Optimization and Best Practices, accessed on January 19, 2026

- Intrusive Interstitials & Mobile SEO Penalty – Branch.io, accessed on January 19, 2026

- Interstitials and dialogs: How to fix intrusive pop-ups and overlays – Search Engine Land, accessed on January 19, 2026

- ADA Compliance and SEO: Non-Compliant Websites Hurt Rankings | Oyova, accessed on January 19, 2026

- The Role of Accessibility in Local SEO for WordPress, accessed on January 19, 2026

- Guidance on Web Accessibility and the ADA, accessed on January 19, 2026